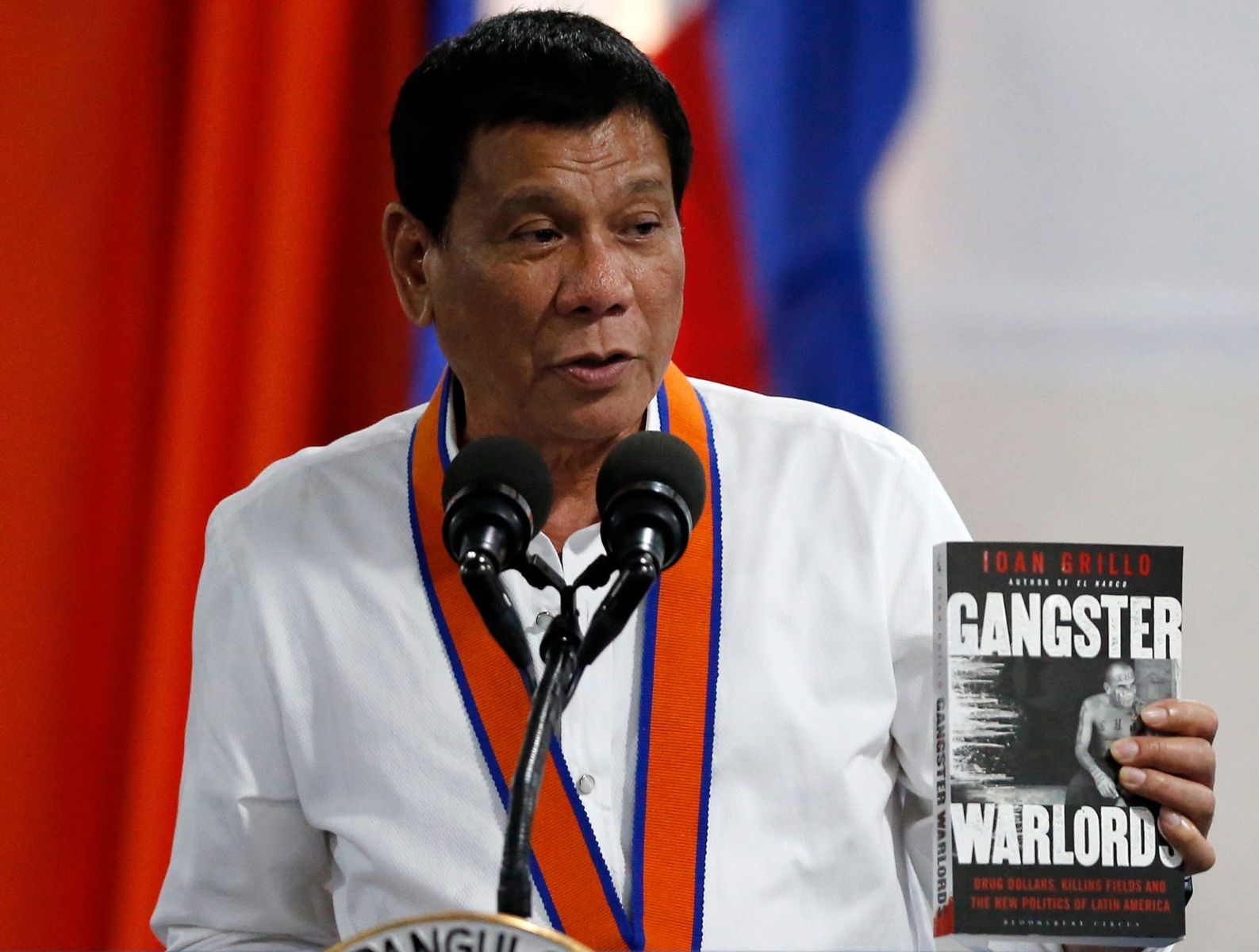

EFE / Francis R. Malasig

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, promised in 2016 to end drug problems in his first six months of office using questionable selective assassination strategies.

By now, it is widely accepted in the international human rights movement that one of the purposes that was served by “naming and shaming” during the past four decades has declined in significance. That is, persuading Western governments to exert pressure on governments in other parts of the world to curb abuses of rights is increasingly ineffective. This has become particularly obvious in regards to the United States. President Donald Trump is more likely to praise the ethnic-nationalist leaders of illiberal democracies, such as Putin in Russia, Orban in Hungary, Erdogan in Turkey and Duterte in the Philippines, for their abuses of rights than to criticize their practices. He is even willing to heap praise on out-and-out dictators who commit gross abuses of rights such as Sisi in Egypt and Kim Jong Un in North Korea. The leaders of a few other Western countries occasionally speak out about human rights abuses, but this does not often seem a priority for them, and their remarks do not seem to carry much weight.

Though both US Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama spoke out more often on human rights, and generally avoided identifying themselves with governments that were highly abusive, the influence of Western governments in promoting rights in other parts of the world was already in decline. The Bush administration’s use of prolonged detention without charges and torture against suspects in its “war on terror” had undermined the credibility of the United States in speaking out against a range of abuses by other governments. Though the Obama Administration renounced torture and attempted to close Guantanamo, it did not fully overcome the damage done by its predecessor; and it did not seem to attach a high priority to efforts to influence the human rights practices of many other countries. European voices in that era were also relatively muted.

The foreign policy rationale for naming and shaming has not played a very important role in promoting human rights in the period since about the beginning of the present century. However, the value of gathering and disseminating highly detailed and reliable information on human rights abuses worldwide is of undiminished importance. It serves several other purposes.

First, it is of immense importance to victims of human rights abuses that their suffering, and the identities of those responsible for their suffering, should be known. It is the near universal experience of those conducting human rights research that victims want to tell their story, want it to be recorded and want the information to be disseminated as widely as possible. When they have the opportunity to make their experiences known, even if it is long after the abuses took place and there seems no possibility of holding anyone accountable, they will readily provide as much information as possible to human rights investigators.

Second, detailed and reliable information is needed within countries where abuses have taken place if efforts are to be made to secure changes. The information gathered by both local and international human rights organizations is of great value. As the latter are often not susceptible to allegations that they are pursuing a domestic political agenda, and because it may be easier to persuade others that their manner of gathering the information adhered to international standards, their data may have great value in supplementing the efforts of local groups.

Third, though Western governments may not use detailed and reliable human rights information to try to influence the practices of the governments responsible for abuses, most abusive governments feel that they must take into account international public opinion. Vladimir Putin in Russia is the country’s most powerful leader since Stalin ruled the Soviet Union. Xi Jinping in China is that country’s most powerful leader since Mao. Yet one important factor that makes it unlikely that Putin will ever commit abuses comparable to those of Stalin, or that Xi will ever commit abuses comparable to those of Mao, is that they are constrained by international public opinion. There was no international human rights movement in the days of Stalin or Mao with the capacity to document abuses. Today, even when abuses occur in a remote place, such as the right violations that China has committed against the Uighurs in Xinjiang, one can be certain that, despite the immense difficulties, those abuses will be carefully and reliably documented by international human rights organizations. China’s awareness that this will take place, and that it has an impact on international public opinion, is probably the most important factor limiting the extent and the severity of those abuses.

Fourth, by now there have been a good many cases in different parts of the world in which high level officials, among them heads of state, heads of government and military commanders, have been held accountable for severe abuses of human rights. They include large numbers of officials of the Latin American military dictatorships of the 1970s and the 1980s; many of those responsible for the most severe abuses in ex-Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the 1990s; and some of those responsible for atrocities in African countries such as Sierra Leone, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mali and others. The fact that those convicted for such abuses are serving long prison sentences, or have died in prison, is not lost on officials in other places where such crimes might be committed. By now, the number of circumstances in which criminal accountability has taken place has reached a point where it has brought about some measure of deterrence. Gathering, documenting and disseminating reliable and detailed information on abuses—that is “naming and shaming”—is the essential means of promoting accountability.

During an earlier era, starting with the Carter Administration in the case of the United States, naming and shaming played a useful role in persuading Washington to try to promote human rights internationally. Yet that was never the most important reason for gathering, documenting and disseminating reliable information on human rights abuses. Naming and shaming remains what it has been for a long time: probably the most effective weapon available to the international human rights movement in promoting its cause.