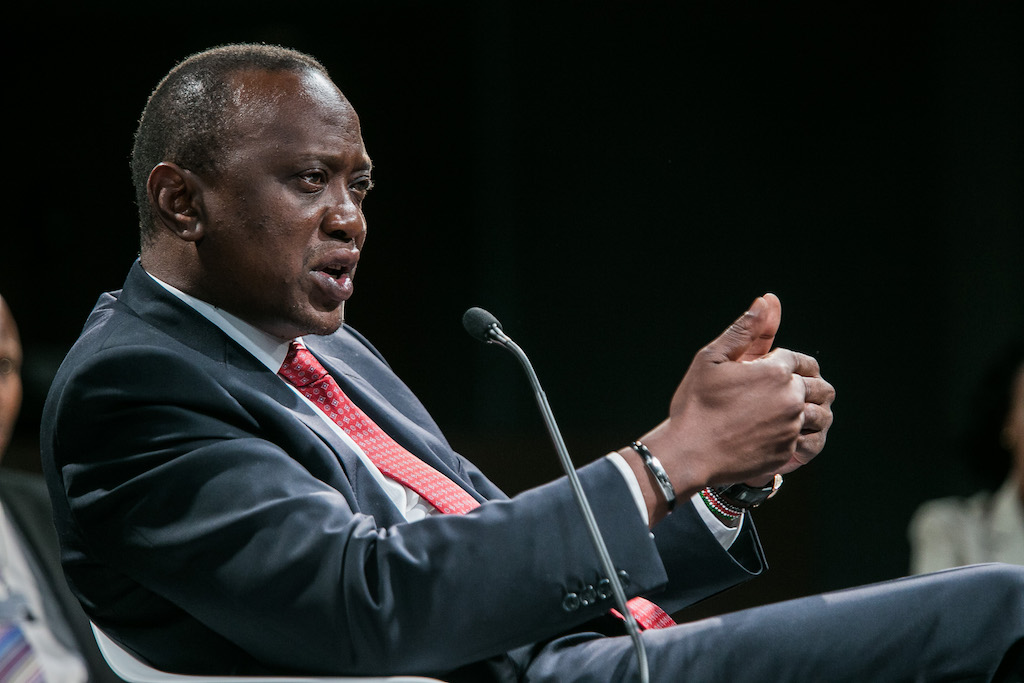

Recently, President Uhuru Kenyatta won a second consecutive term in office in Kenya. Yet, only six years prior, he was officially charged by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for orchestrating post-election violence in 2007 that was grave enough to qualify as crimes against humanity.

As disparate as these two events may seem, new research I am involved with suggests that they are likely related. In a well-resourced campaign between 2011 and 2017, Kenyatta framed the ICC as a “neo-colonial” court that violates Kenyan sovereignty and shows bias against Africa. This narrative resonated with a group large enough to produce majority electoral victories in 2013 and 2017.

First, it’s important to understand Kenyatta’s political victories since 2011: he formed the Jubilee Alliance with fellow ICC target and former ethnic rival William Ruto, then won election to president in 2013. He watched as Kenyan support for the ICC plummeted from 70% in 2010 to just under 40% in mid-2013. He celebrated as the ICC dropped his case in late 2014, citing obstruction and witness tampering. He enjoyed the fruits of diligent international campaigning in early 2017, when the African Union passed a resolution calling for states to withdraw en masse from the Rome Statute. And along the way, he even got to cavort with President Obama.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the anti-ICC narrative played a role in the president’s political fortunes.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the anti-ICC narrative played a role in the president’s political fortunes.

To understand how, a group of researchers and I used original survey evidence from Kenya to examine what drives the belief that the ICC is biased against Africa. In coordination with local partners and The Hague Institute for Global Justice, my co-authors administered the survey in October 2015. A team of ten Kenyans interviewed 507 randomly selected citizens in five regions most affected by the 2007 post-election violence. The sample closely approximates the ethnic composition of the country, though it slightly over-represents male and educated individuals.

Figure 1

The first thing we found is something that we already knew from visiting the country: Kenyan opinions are informed, diverse, and complex. All but four of 507 respondents said they were familiar with the ICC, and 70% said they had learned of the Court from politicians. Over three-quarters of Kenyans surveyed think prosecutions are the best option for those guilty of planning 2007 election violence, and the same proportion do not agree that the “ICC has no right to charge Kenyans with crimes.” However, only 44% agree that the ICC “promotes justice” (see Figure 1).

Regarding belief in the state-sponsored narrative that the ICC is “biased against Africa,” Kenyans in our sample are split: 46.1% disagree; 34.3% agree; and 8.3% don’t know or remain neutral (For more, see our original post here). What determines an individual’s stance on this issue?

Many scholars and observers assume that Kenyans form political opinions solely based on material interests defined down ethnic lines. Of course ethnic patronage is the main driver of Kenyan politics, but if it were the most important determinant of belief in ICC bias, we would expect Kikuyu and Kalenjin respondents—who support President Kenyatta and Deputy President Ruto, respectively—to agree wholesale with the story supported by their co-ethnic leaders.

This is not the case. Only 53% of all Kikuyu and Kalenjin respondents agree that the ICC is biased. Though ethnic affiliation is significantly correlated to perceptions of bias in multivariate statistical models, it is not the most powerful factor.

One reason for this is that the Kikuyu-Kalenjin coalition undergirding the anti-ICC Jubilee Alliance is odd. These groups fought against one another after 2007 elections, and members of each group were victimized by horrific violence. Compared to average Kikuyu or Kalenjin respondents, those who were exposed to violence—which we define as either witnessing or suffering attacks—are 24.6% less likely to agree that the ICC is biased (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Surpassing ethnic identity and exposure to violence, the most central reason for belief in ICC bias is one’s concern for national sovereignty. We measure this by using responses to the survey item mentioned above, that the ICC has “no right” to charge Kenyan citizens—a factually incorrect statement. Those who agree that the ICC has “no right”, a group comprised of less educated individuals with more trust in Kenyan national courts, are over four times more likely to agree that it is biased against Africa as well.

At play here is what social psychologists refer to as collective identity. In forming a political alliance, and stressing both Kenyan sovereignty and the ICC’s anti-Africa bias, Kenyatta and Ruto transformed themselves from a union of alleged international criminals to an nationalist, anti-colonial movement to be celebrated. This narrative has broad nationalist appeal that transcends narrow, ethnically defined interests.

Our research is not about explaining electoral results, but one could extrapolate the logic behind the anti-ICC campaign waged by Kenyatta and Ruto from our findings. Assuming that the vast majority of their co-ethnics would vote for them out of material self-interest, all it would take is convincing a sizeable portion of the rest of the population to win a majority of the vote. Anti-ICC rhetoric might do the trick. Half of respondents who express a concern for sovereignty belong to communities other than Kikuyu or Kalenjin. This group represents almost 20% of the non-Kikuyu/Kalenjin respondents in the sample. Assuming this anti-ICC group votes for Jubilee, this is enough support to translate into narrow majorities in Kenyan presidential elections.

Flickr/World Economic Forum/ CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 (Some Rights Reserved).

Recently, President Uhuru Kenyatta won a second consecutive term in office in Kenya.

This latest election produced a great deal of anxiety. Only a week before, Chris Msando, an electronic voting machine expert on the Kenyan national election board, was tortured and murdered. Kenyans battened down the hatches, the international community fretted, and President Obama interrupted his vacation from politics to urge calm before election day.

In the end, Kenyans turned out and peacefully cast their ballots. The votes were counted. Though opposition leader Raila Odinga cried conspiracy, and police killed over 20 protestors, the country did not see a repeat of the high violence recorded in 2007.

What did repeat was a Jubilee victory. Part of the reason is the power of the collective identity forged through Kenyatta’s campaign against the ICC. Crucially, though, those seeking justice for mass violence perpetrated in the country’s recent past do not share this collective identity. They are still losing in Kenya.