The human rights framework has had many successes in the 70 years since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted, but is it still relevant to today’s challenges? To be so, it must continue to evolve and address the issues of most concern to most people. Three proposals deserve consideration: (i) put climate change at the top of the human rights agenda; (ii) significantly increase human rights NGOs advocacy on economic and social rights (ESR); and (iii) adopt a more solutions-based approach to human rights.

The UN Human Rights Council adopted the first of several resolutions on the human rights implications of climate change in 2008. Despite this, human rights advocacy has, until recently, overwhelmingly placed people above our natural environment, failing to respond to the dual crisis of environmental destruction and climate change. This is changing, but not fast enough. Blocking progress is the continued prioritization of civil and political rights by many human rights NGOs, at least in the global North.

Further, the human rights framework is, in practice, usually used in relation to what can be termed direct human rights violations; for example, denials of the right to food. Reporting on this may include the contextual, proximate causes—for example, reduced crop yields. But only rarely does the human rights approach take a deeper analysis and look at violations as a result of breakdown in systems further removed, such as ecological, economic, or financial systems. These can impact whole societies, or even the global population on a multitude of rights and a prolonged timescale. Climate change—which is often the root cause of poor crop yields—is a perfect example.

The human rights movement needs to embrace environmental protection and climate change action as the top priority for human rights in the decades to come, and in effect become an environmental and climate change movement.

Only rarely does the human rights approach look at violations as a result of breakdown in systems further removed, such as ecological, economic, or financial systems.

Turning to ESR, there is now wide acceptance in the human rights community that there is no hierarchy between rights, yet there is still a widespread, disproportionate focus on civil and political rights. The UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights noted in 2016 that the preponderance of the work of the UN Human Rights Council focused on civil and political rights.

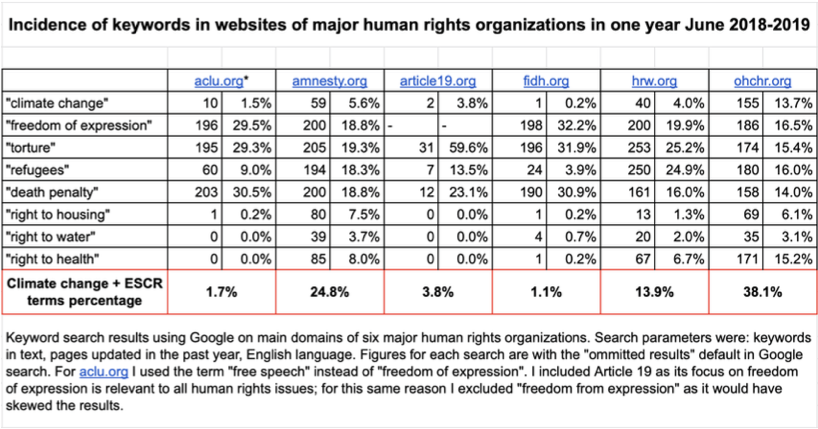

There is very little, if any, quantitative data on the proportion of their work major human rights NGOs devote to ESR. But a simple set of google searches can give some indication.

Of course, foundational rights such as freedom of speech and freedom of assembly are severely curtailed in many countries—and without them, it is not possible for people to demand and put pressure on governments to respect their other rights, including economic and social rights.

But international and national human rights NGOs and institutions, and UN bodies, must elevate ESR much higher up their agenda. This is critical to grow support and commitment for human rights among the public in the first place, and as an indirect consequence, governments’ commitment to human rights.

Violations of rights to freedom of expression and assembly, the right to life, freedom from torture, and access to justice—these are issues that impact directly only a small proportion of any given population at any given time (bar in exceptional circumstances, such as armed conflicts). On the other hand, access to healthcare, education, work, and housing directly impact almost everyone in a given population.

This doesn’t mean that civil and political rights are less important to people—only that their impact is often felt in moments of crisis—when someone has a problem. On the other hand, health, work, education, and housing are much more palpable issues day in and day out.

Here human rights are often in competition with politics: for people to actively care about the human rights message, particularly that of equality and non-discrimination, they must see greater human rights protection as the means for a better future. Without this, human rights risk being seen as something that only benefits those perceived as “other”: refugees, people in faraway conflicts, and the minority of the population who are politically active.

The best way to protect the rights of minorities, refugees and disadvantaged groups in a society, is to have widespread support for human rights. When people hear a human rights message that speaks to their needs, they are more likely to be receptive to a human rights message about the needs of others. If the backlash we have seen against human rights across the world is any indication, the opposite is equally likely to be true.

For people to actively care about the human rights message, they must see greater human rights protection as the means for a better future.

Major human rights organizations should change the balance of their work to something much closer to a 50/50 split between civil and political rights, and economic, social and cultural rights.

Finally, there is the need to provide solutions. In some cases, these are relatively straightforward—for example, ending torture in police custody and ending legal threats against independent journalists. These require many steps and much work to achieve in practice, but if a government has the willingness, it will know what it needs to do.

The same cannot be said for all human rights problems: for example, for access to healthcare, or the right to work, the answer is often not straightforward. The fulfilment of these rights is almost always subject to resource-constraints. There is also seldom one right answer to questions such as whether healthcare at the point of service should be free, or the human rights threshold for treatments that should be available in a public health system, or the correct level for a minimum wage.

Exposing human rights abuses is incredibly valuable in and of itself, but we must not stop there. Human rights organizations should also propose practical solutions that a government—or a company that accepts it must change its practices—would be able to implement.

These solutions should go beyond legal changes. As human rights advocates and practitioners, we must embrace the complexity of the world and see human rights as one of multiple, interacting systems needed to achieve individual, societal and planetary well-being. These include economic, fiscal, political and technological systems, among others.

It’s important not to fall into the trap of thinking that the human rights framework has the solution to every sociological, political or economic problem. The human rights framework’s legal standing, wide acceptance and international nature make it essential for sound governance. But to think of it as the answer to everything, is to set it up for failure.

We must also increase our outreach and collaboration with other sectors—scientists, economists, politicians, businesses and others, without whom the ideal of universal enjoyment of human rights can never be achieved. If we want to get to a world where everyone enjoys their human rights, civil society, governments, business (and others) must collaborate to achieve this. Exposing violations and abuses is always needed, but working together towards solutions for protecting rights is even more important.

This piece is a shorter version of a paper written for the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, at Harvard Kennedy School, which can be found here. An adaptation of the piece was used in part of the Next Strategy planning process at Amnesty International. It represents the personal opinion of the author.