For the past seven years, the Advancing Human Rights research has mapped the landscape of human rights philanthropy to help funders and advocates better understand the field and to answer the question: “Who is funding human rights, and where?” This initiative is a collaborative effort between Foundation Center and the Human Rights Funders Network, along with our partners Ariadne – European Funders for Social Change and Human Rights and Prospera – International Network of Women’s Funds.

We recently launched our latest findings on our interactive research hub. With multiple analyses and five full years of data under our belt, we were able to explore trends in human rights grantmaking for the first time. In this research, we analyzed any grant that met our definition of human rights funding, regardless of whether the funder self-identified as supporting human rights. Grants ranged from multimillion-dollar core support grants to a US$24 grant for a feminist dialogue in Chile.

Our latest data collection and analysis efforts reveal that human rights and social justice funding grew by nearly 45% from 2011-2015, from US$1.4 billion to over US$2 billion. Over these five years, 1193 funders made at least one human rights grant and were included in our research. However, not all of those funders shared data each year. To account for this variation, the trends analysis draws from a subset of 561 funders who shared grants data for each of the five years, 2011-15. Total figures (for both this matched subset as well as the larger sets for each year) are available on the research hub.

While we can’t speak to the unique priorities of hundreds of funders, some have actively devoted more funding to human rights, responding to new opportunities and needs on the ground. The growth also reflects possible shifts in how the data was reported to us: funders submitting more—or more detailed—grants data each year, as well as more funders framing their work as human rights. Over these five years, we’ve encouraged funders to share detailed data that captures the nuance of their work in complex areas of rights. The difference between a grant described as “project support” and one described as “project support to a youth-led organizing campaign to advocate for expanded access to education for immigrants and refugees” determines how accurately we capture the work and how we identify it.

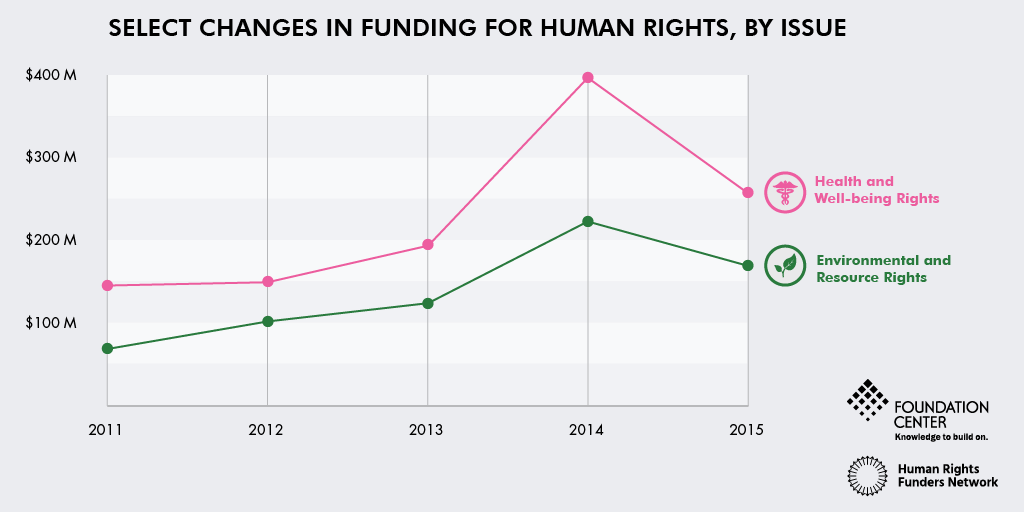

Several issue areas showed notable growth from 2011-15: for example, funding for Environmental and Resource Rights more than doubled, from US$69 million to over US$169 million. This is exciting but not necessarily surprising. The intersection of human rights and the environment is common in conversations among funders, and the data reflects increased funder engagement: 167 funders made an environmental and resource rights grant in 2015, an increase of 28% over 2011.

In addition, funding for health and well-being rights grew from US$145 million to US$257 million. Like the environment, health can sit at the nexus of human rights and other fields like international or community development. US funders who don’t call their work “human rights” are increasingly framing healthcare grants in terms of access and equity. For example, the California Endowment was the top funder for health and well-being rights in 2014; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation topped the list in 2015, in part due to their Culture of Health grants addressing systemic factors that affect health, well-being, and equity. While we can’t tap into their internal strategic thinking, this shift in language and framing is key. Indeed, in 2011, funding from those who don’t self-identify as rights funders accounted for 37% of funding for health rights. By 2015, this cohort’s funding grew to represent 51%.

The field of human rights philanthropy has grown, too: The Freedom Fund, for example, was established in 2013 to support frontline efforts to eradicate modern-day slavery. Funding for Freedom from Slavery and Trafficking has since nearly doubled. FRIDA | The Young Feminist Fund, which supports organizing among emerging feminist groups, collectives, and movements, announced its first grants in 2012, and funding for grassroots organizing has more than tripled. The creation of these new funds may have influenced their peers—the power of funder advocacy—but they likely reflect and harness movements already rising within the field.

Despite overall growth among this matched set, we’ve also seen notable dips. Funding for disability rights dropped by 23%—the only one of our key population groups to see a decrease. The relatively small amount of funding makes this area susceptible to dramatic year-to-year shifts, but the decrease also mirrors a frustrating reality: the disability community has often had to make the case that they are a member of the human rights family. Ford Foundation’s recent evolution in this area and a report from the Channel Foundation, Disability Rights Fund, and Wellspring Advisors illustrate this challenge.

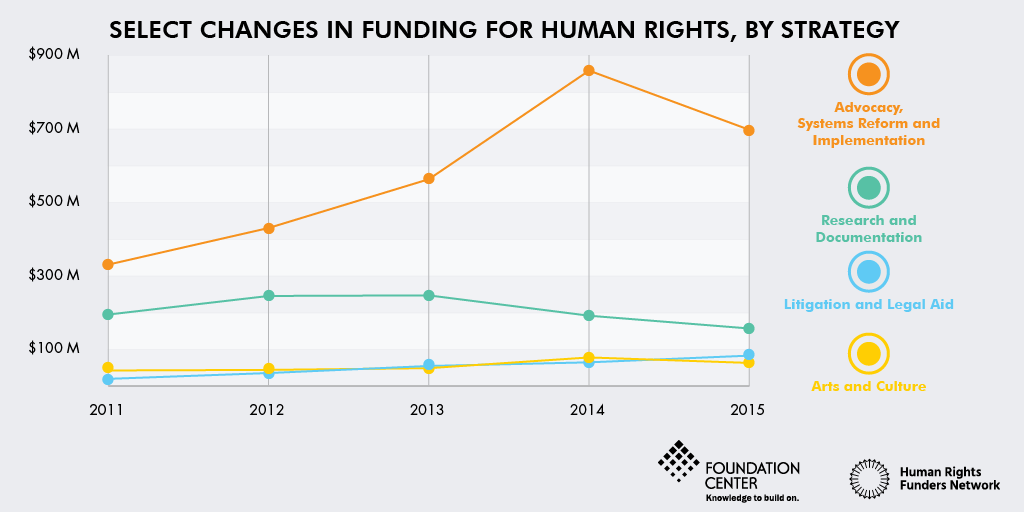

Another drop was in support for research and documentation, which decreased by 19%. Of the eleven strategies we track, this may be closest to a traditional understanding of human rights work: fact-finding and documenting human rights abuses. Interestingly, as arts and culture and strategies aimed at achieving and sustaining systemic change, such as advocacy or strategic litigation, saw substantial growth, major funders’ investments in research and documentation decreased. We can only speculate as to funders’ motivations, but these shifts align with conversations throughout the Human Rights Funders Network in recent years, as funders explore ways to break out of the traditional “human rights” mold and employ creative new strategies to effect change.

But perhaps the most striking dip is not a trend at all. Overall human rights funding grew each year of the research, but it decreased in 2015 (to US$2 billion from US$2.3 billion in 2014). Some reasons are obvious—for example, the Atlantic Philanthropies, a major human rights funder, had mostly spent down by 2015. In addition, with growing concerns around civic space and digital security, some funders choose to share fewer details on grants. Other shifts raise more questions than answers. Among those who identify as “human rights funders” and those who don’t, does a decrease indicate a shift in their priorities? We may not know until we see the next year’s data.

That’s the beauty of this trend analysis. Year-to-year fluctuations can be influenced by a number of factors, but drawing from five years of data allows us to look beyond caveats and identify consistent trends in the field. We can see where human rights philanthropy as a whole is headed—and where it still has work to do.

But do these trends reflect the reality of human rights movements? Will they continue? How well does this “matched subset” reflect a broad and diverse field? Similar questions can be applied to any big data project. But as we acknowledge the gaps in the Advancing Human Rights research, we also recognize what it represents: a first-ever mapping of the field. We now have data to back up our discussions on underfunded areas and intersections in the field—and equally, we know what we don’t yet know. A number of questions remain, and we look forward to diving into them and opening up topics of debate and discussion as we share the trends analysis.

This research would not be possible without the guidance and support of our Advisory Committee, as well as the funders who thoughtfully report their data to inform this research.