About 54% of Mexican adults—over 44 million people—report having donated to the Teletón and other big Mexican charity fundraisers. In 2012, the Teletón, which helps disabled children, raised some $472.5 million Mexican pesos, roughly $35.5 million USD. Yet, only 4% of Mexican adults report having ever given money to a human rights organization (HRO) of any kind, at any point in their lives.

Mexicans feel warmly towards the phrase “human rights”, trust rights groups, and reject claims that human rights are a foreign imposition.

Why do Mexicans—like so many other people worldwide—give less to rights groups than other organizations? We know it is not because of their beliefs and attitudes; our survey research clearly shows that Mexicans feel warmly towards the phrase “human rights”, trust rights groups, and reject claims that human rights are a foreign imposition.

Nor is it true that Mexicans are too poor to donate. The World Bank classifies Mexico as an “upper middle income country”, and it has been a member of the OECD, a rich-country club, since 1994. Some Mexicans are poor, of course, but others have disposable income. Besides, poor people are sometimes far more generous, relative to their incomes, than the wealthy.

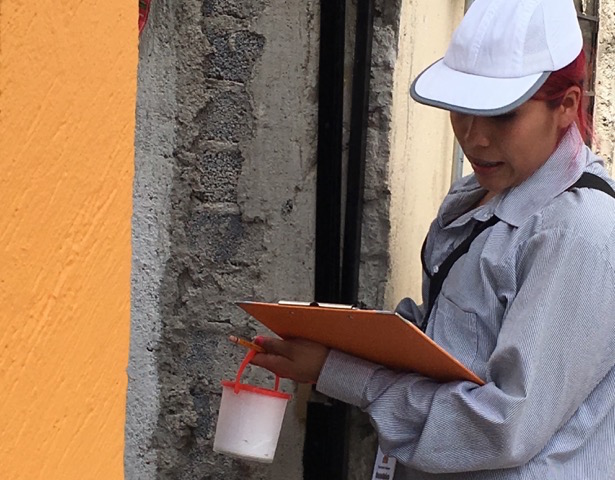

James Ron (All Rights Reserved)

An enumerator prepares to conduct the survey experiment in Mexico City, June 2016.

Research shows that Mexicans do in fact donate to all manner of groups and causes, like many other publics worldwide. They are not the most generous of donors, globally speaking; the World Giving Index recently ranked Mexico at 105 of 140 countries in the “donating money" category. Still, Mexicans donate; in 2016, according to our research, 15% of Mexico City residents said they had donated to parent-teacher associations, while 14% had donated to religious organizations. Only 6%, however, reported having donated to a human rights organization of any kind, broadly defined.

One reason Mexicans don’t donate to rights groups is because of the way these NGOs market themselves. Many emphasize testimonials from individual victims; our study, however, showed that evidence of fiscal transparency and effectiveness would do better. The bigger story, though, is habit: human rights groups simply aren’t on Mexicans’ everyday radars as logical recipients of routine charitable giving.

Can the Mexican public’s donation habits be changed? To find out, we explored the effects of what we call the human rights “brand”. Marketers think of brands as the sights, sounds and ideas that consumers associate with value. Human rights organizations in Mexico have good reputations, but are not the only organizations vying for Mexicans’ pocketbooks. Large corporations often establish charitable foundations such as the Teletón, and many Mexicans give to religious organizations. Our first question, then, is this: in Mexico, how does the human rights brand compare to those of the corporate and religious sector?

Of course, rights NGOs also compete with one another. Extending our marketing analogy, potential Mexican donors can choose among multiple “product lines” within the human rights “brand,” including political rights, women’s rights, LGBT rights, and more. Thus, our second question is: which human rights advocacy areas can attract the most donations?

Non-profit groups everywhere are also distinguished by their decision to either offer direct support to persons in need (for example, giving cash to needy families) or to work on long-term policy and legal change. In our Mexico City focus groups, for example, many told us they prefer the direct assistance of the Mexican Red Cross to the more indirect work of public policy advocates. As a result, we identified our third question: will Mexicans donate to policy-focused rights NGOs?

To investigate these questions (human rights “brand value”, the appeal of different advocacy areas, and charitable assistance vs. structural change), the Human Rights Perceptions Polls at the University of Minnesota teamed up with the Mexican public research center, CIDE to conduct a face-to-face, representative survey of 960 Mexico City inhabitants in July 2016, with financial support from the Open Society Foundations.

Our survey contained an experiment designed to find out which organizational types are most likely to inspire donations. We presented each respondent with two sets of four hypothetical organizations and asked them to distribute $100 imaginary pesos among the four groups in each set. We varied the organizations’ attributes to see which garnered the most donations. This experiment simulates the actual choices a potential donor, or consumer, might make when faced with the need to make real decisions (it is known in market research as “choice-based conjoint analysis”).

We varied our hypothetical organizations on three attributes. The first was “brand”, identifying groups either as a Mexican organization of “lay Catholics” (religious brand), “business leaders” (corporate brand), “movement of Mexican citizens” (social movement brand), or “Mexican human rights organization” (human rights brand).

Our second attribute was “issue”, noting that organizations worked either on women’s rights, LGBT rights, access to clean water, or forced disappearances, all prominent themes in Mexico. Finally, our third attribute was “activity”: organizations were either engaged in direct relief activities, such as providing economic support to persons in need, or strategic activities, such as pressuring authorities to punish rights abusers.

We found that “human rights” and “social movements” were the most successful brands. The average donation to human rights-branded groups, regardless of issues or activities, was $26.30 pesos. Social movement-branded groups were slightly higher, at $27.84, and the two lowest were $22.03 for the corporate-branded and $19.77 for the religious-branded. In Mexico City, in other words, the “human rights” brand offers a real competitive advantage.

Not all rights groups were equally successful, though. The most heavily rewarded issue area was “access to potable water”, with $28.50 pesos, on average, followed by “women’s rights”, a close second ($27.16). The runners-up were Mexican groups combatting forced disappearances ($24.51) and struggling for LGBT rights ($15.71).

Encouragingly, we found that in Mexico City, rights groups can be successful either by committing to short-term assistance or by engaging in long-term advocacy. Average hypothetical contributions to direct relief organizations were only marginally higher, by $2.12 pesos, than contributions to organizations that pressured the government to prosecute abusers. The difference was statistically significant but small.

It is not news to say that different people support different issues and organizations. Our experiment puts meat on those spare bones, showing that human rights organizations can successfully compete in the Mexico City charitable donations market, and demonstrating which issues are likely to attract more money.

Monetizing the human rights “brand” will require new financial and cognitive investments in staff, fundraising techniques, communications abilities, donation modalities, accounting systems, and more. Our research suggests these investments will be worth the effort.