Is it possible that human rights are a myth?

To ask this question is likely to be perceived as advocating for a dismissal or even a rejection of human rights. Indeed, when the term “myth” is used in conjunction with human rights, it is almost always done with the intention of discrediting either the idea or the substance of human rights.

This tendency to associate “myth” with error or duplicity actually prevents us from recognizing some important insights.

As a scholar of religion, however, I have argued that it is misleading to think of myth in this way. In fact, this tendency to associate “myth” with error or duplicity actually prevents us from recognizing some important insights that the category of myth sheds upon the history and the logic of human rights.

The foundational document of contemporary human rights, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, sits uncomfortably within today’s broad corpus of international law. This document was advertised by its creators as emphatically secular even as these creators regularly used religious discourses of sacredness and veneration to describe it.

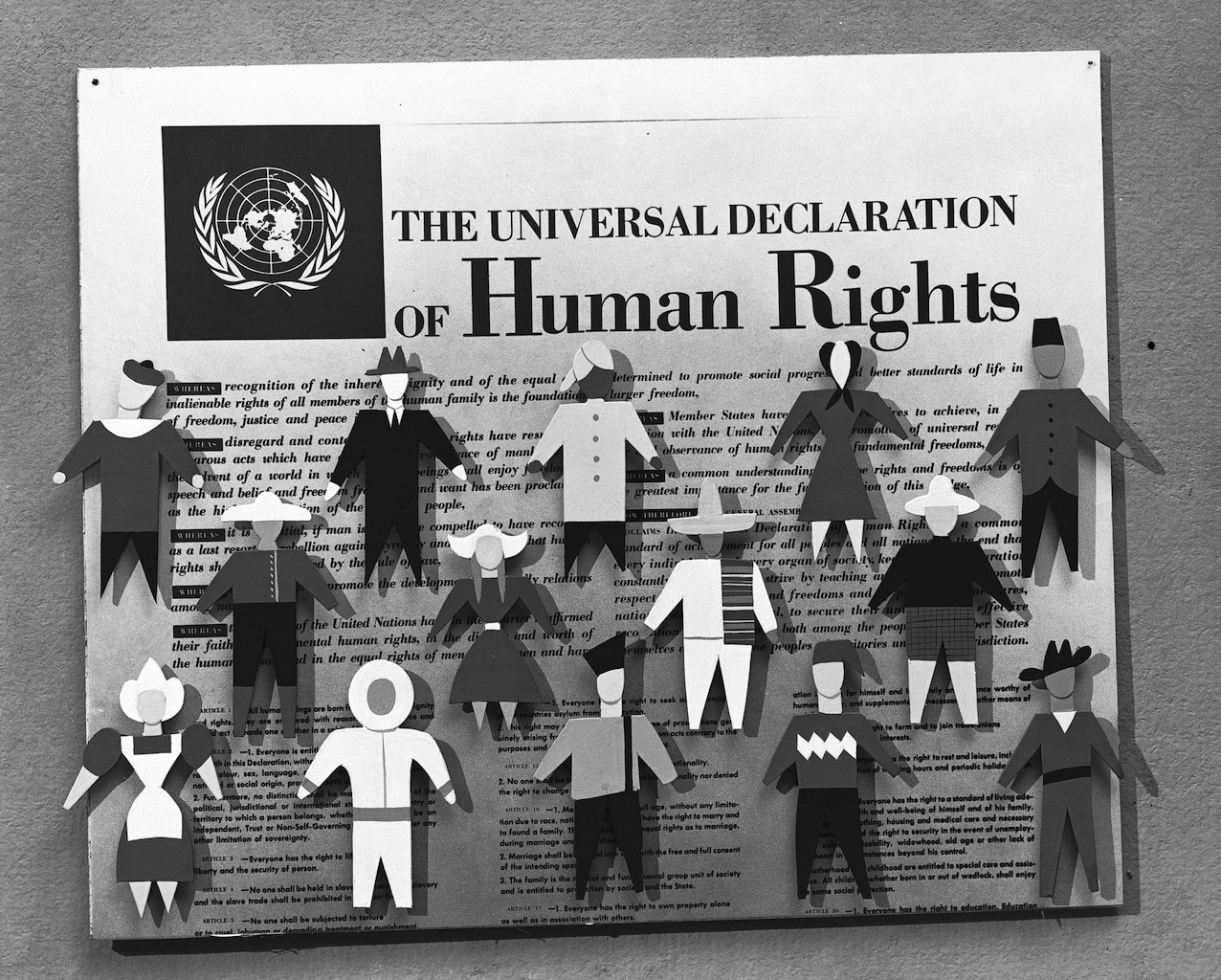

Flickr/UN Photo/Photo # 329493 (Some rights reserved)

The framers of the Declaration aspired to generate a document capable of rectifying the horrors of World War II by establishing, in the words of Commission chairwomen Eleanor Roosevelt, “why we have rights to begin with.”

The Declaration proposes no mechanisms for the enforcement of its provisions, yet there is much evidence to indicate that it has come to command a significant “moral” authority. Indeed, the first UN Commission on Human Rights actively aspired to imbue it with such an authority. Ultimately, in fact, there is much in the historical record of the creation of this document to indicate that many Commission members were deeply convinced of the Declaration’s capacity to transform the ethical and even the metaphysical landscape of international law.

The phenomenon of myth provides a valuable lens through which to make sense of these various conflicting elements in the Declaration. Far from understanding myth as a mode of erroneous or deceptive discourse, scholars in the field of religious studies understand myth as a form of human labor that serves the function of generating meaning, solidarity, and order within all manner of human communities. Far from being characterized by their inaccuracy or duplicity, myths are characterized within the study of religion by the particular authority they wield and the particular strategies their creators use to imbue them with this authority. In short, instead of offering arguments or strictures, myths are narratives that assert their descriptions of the world, and the moral imperatives stemming from these descriptions, in a way that makes them appear beyond dispute.

Mythmakers accomplish this authoritative assertion of information in a variety of ways—for example, by describing the prescriptions of supernatural beings, by narrating the feats of exemplary figures from earlier times, or by drawing connections between the present and a paradigmatic moment in the past. In all of their variety, such narratives are united in their effort to set language to the task of, in words of Roland Barthes, “lending an historical intention a natural justification, and making the contingent appear eternal.”

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, an emphatically secular document, obviously makes no appeal to supernatural realms or superhuman beings. It does, however, narrate its basic tenets in the unequivocal manner characteristic of myth. The framers of the Declaration aspired to generate a document capable of rectifying the horrors of World War II, and they aimed to do so not merely by enumerating certain rights but also by establishing, in the words of Commission chairwomen Eleanor Roosevelt, “why we have rights to begin with.”

To accomplish this, the Commission worked to imbue the Declaration with a logic that would place its basic tenets beyond question. They worked, in other words, to create a secular narrative capable of wielding the authority of a religious one—a narrative that would appear to everyday people, in the words of Soviet delegate Vladimir Kortesky, “as simple and as clear as the Decalogue.”

How does one create a “Decalogue” (i.e., the Ten Commandments) that is sufficiently secularized to command global legitimacy? This problem of how to articulate a set of evocative principles in the absence of shared metaphysical foundations reaches to the heart of the twentieth-century human rights project. Members of the Commission recognized early in their negotiations that a human rights vision geared toward a global audience could not ground its claims within any culturally-specific worldview, lest it appear to be imposing rather than merely reiterating fundamental values. In the face of this conundrum, the Commission simply proclaimed, in the very first words of the Declaration, the inherence of “human dignity”—a proclamation made, as is often the case in myth, without rational argumentation of any sort.

“Inherent human dignity” functions within the Declaration as an axiom located beyond dispute or question. It is a characteristic that, as human right scholar Johannes Morsink puts it, “no person and no political or social body or organ gave us” and that, therefore no person or political/social body is empowered to violate. Such dignity functions in the Declaration not merely as an elementary human characteristic but, in the words of Lebanese delegate Karim Azkoul, as “an absolute and general principle.”

Much more than a basic human trait, inherent dignity serves within the Declaration as a sacred center—an item unequivocally set apart for veneration as both an emblem of human rights and a guarantor of the faithful observance of the Declaration’s prescriptions.

At a seminal moment in the history of international law, universal human rights were created to push deliberately against two longstanding human tendencies: the tendency to tie human rights to one’s membership within a particular political community, and the tendency to hearken to the realm of the divine when building a foundation for political ideals and practices. This twofold endeavor gave rise to a document the likes of which has never been seen: a declaration that predicates its tenets upon a universal, secular human reality that it brings into existence through no other means than by professing to recognize it.

Yet, for all the novelty of this maneuver, the first Commission on Human Rights undertook its work in a way that smacks of the time-honored logic of mythmaking—a logic wherein language is set to the task of unequivocally presenting a vision of the world as well as a set of mandates appropriate to the maintenance of that world. The Declaration’s unique narrative complicates conventional distinctions between “religion” and “secularism”, and, in so doing, sheds new light not only on these often-take-for-granted categories, but on the nature of human rights themselves.