Can Human Rights Deal with Existential Risks to Humanity and the Planet?

1/22/2021

If a pandemic, the climate crisis and the persistence of authoritarian populism have taught us anything, it is the importance and urgency of focusing on existential challenges to human rights and to the future of humanity and the planet. The need to anticipate, discuss, and shape the future of the field is even greater after the tumultuous beginning of the 2020s.

But how far into the future should we look? My answer: very far. This means taking seriously those challenges that pose risks to the survival or basic welfare of the human species and the biosphere, and whose impacts are measured in centuries as opposed to years.

Read more:

Yet, the emphasis in human rights practice and scholarship is squarely on the short-term. On the advocacy front, immediate responses are needed to prevent or redress human rights violations. Relatedly, organizational strategic plans and funding cycles tend to run for two to three years at best. On the academic front, though most researchers have yet to ask the question about the time horizon, some, arguing that we are supposedly in the “endtimes” of human rights, seem to have prematurely concluded that the question is not even worth asking.

I have argued that this blind spot stems from a more general blindness to issues of time (as opposed to space) in the human rights field. This is evident, for instance, in the neglect of future generations in human rights concepts and norms. Taking a classic example, when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights proclaims that “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” it considers only present generations because its provisions do not prevent them from leaving an uninhabitable planet to future generations.

Here I want to sketch a long-termist view of human rights. From this perspective, the “human” in “human rights” encompasses not only the nearly eight billion people alive today (including young people who are likely to face existential threats in this century and the next) but also the innumerable generations yet to be born..

This view builds on recent work on long-termism in moral philosophy and in interdisciplinary fields such as global priorities research and effective altruism. It also draws on ecological and Indigenous knowledge – as reflected, for instance, in the seven-generations principle of the Haudenosaunee Indigenous people of North America, according to which decision makers need to act in the interest not only of present generations but also of the next seven generations.

Rather than a distant concern or a purely intellectual heuristic, a long-termist approach brings three key practical questions to the fore that have received scant attention in human rights. The first issue is impact. Activists go into human rights work, often at considerable cost to their individual well-being, because of an altruistic commitment to helping other people or improving the world more broadly. Yet questions about who those “other people” should be or how they can be most effectively helped have not been systematically tackled. “Impact” remains a vexing and elusive issue at best, or simply the heading of an uncomfortable section to fill out in standard reports to funders at worst. As empirical research on effective altruism has shown, well-intentioned and selfless actions that seem intuitively laudable may have a small positive impact when compared to other less obvious options. For instance, the human cognitive bias towards information that is readily available may generate disproportionate focus on sudden natural disasters relative to even more massive, yet less visible human rights violations, like the daily deaths stemming from lack of access to health care. A long-termist perspective corrects for this bias by making visible and addressing the “slow violence” of long-term injustices against people and the planet.

The second issue brought forth by a long-termist perspective is that of priorities. Once the relative impacts of different alternatives have been assessed, questions about which topics or strategies to prioritize become pressing. In light of resource constraints, what should a given human rights organization or collective prioritize (e.g., research v. advocacy, legal v. communications work, civil rights v. social rights, etc.)? Which topics should researchers and funders focus on? Which topics or challenges should the field as a whole prioritize for the future?

Prioritization is not common currency in the human rights field. Among practitioners, the very source of moral strength of the movement – the commitment to the equal dignity of all – oftentimes translates itself into an understandable impulse to commit to all issues equally. Hence the persistent difficulty of many advocacy organizations in narrowing down their list of causes or changing priorities in light of new contexts. However, if everything is a priority, then nothing is a priority.

Many human rights scholars are also reluctant to delve deep into priorities research because they hear an echo of cost-benefit analysis, which was traditionally dominated by the narrow-minded approach of neoclassical economics. However, this is just one among many approaches found in the rich long-termist debates in moral philosophy on impact and priorities. Since, as Amartya Sen has argued, human rights are ultimately an approach to ethics (as opposed to a mere set of legal rules), long-termism should be a fertile ground for human rights research as well.

And third, long-termism raises a new set of questions about the relevant rights-holders. Put simply, long-termism is the view that “people matter just as much no matter when they exist.” As noted, this means that the rights-holders to be protected are those belonging not only to the present but also to the future. This shift in perspective is particularly urgent, as we have amassed technological power that can put at risk not only all those alive today, but all of those who could follow us as well.

Adopting a long-termist view has profound implications for human rights and lays out new work and questions for activists and researchers. For instance, in light of the evidence from research on existential threats to humanity, are there any human rights topics that need to be prioritized? The evidence points to issues such as the regulation of artificial intelligence, nuclear weapons, climate change, and the production and manipulation of viruses and other pathogens. Short of existential threats, other sources of long-term, massive impact on human rights should also be addressed, such as genetic engineering. More generally, regardless of the issues and the specifics of advocacy and research, long-termism invites us to take seriously the elusive questions, including those on impact and priorities.

From Barbuda to the World: Love (and Peace and Happiness) in the Time of Climate Emergency

By: César Rodriguez-Garavito & Elizabeth Donger

12/11/2020

“The future is already here. It’s just not evenly distributed yet,” the sci-fi writer William Gibson has famously said. For a peek into the future of human rights in a warming planet, there are few better places than the small Caribbean island of Barbuda. Barbuda is a microcosm of larger trends and issues – from climate-induced displacement and disaster capitalism, to greenwashing of policies that undermine climate resilience. If this future is to be avoided in Barbuda and elsewhere, the world must pay close attention to current developments in the island whose stunning calm and beauty made it Princess Diana’s favorite vacation spot and inspired Robert de Niro to call his planned luxury tourism project there, “Paradise Found.”

Read more:

The first thing to note is the government’s double standard. In early December, 2020, the central government of Antigua and Barbuda, located on the island of Antigua, virtually convened a meeting of the Latin American and Caribbean states that had signed the landmark Escazú Agreement in 2018. This binding treaty guarantees public participation in significant decisions about the environment, rights to information and access to justice in environmental matters. It also offers important protections for environmental activists, who face acute risks across the continent.

The government self-identifies as “one of the front runners within the region with a progressive climate agenda,” recently receiving $39.4 million from the Green Climate Fund. When the Category-5 Hurricane Irma decimated Barbuda in 2017, a smaller island located 40 miles north of Antigua, Prime Minister Gaston Browne said “Three years from now, we’ll be having a different conversation; we’ll be looking at a Barbuda that’s climate-resilient, that’s totally green.”

Three years later, the conversation is very different. While championing the Escazú Agreement, PM Browne is simultaneously rolling out plans to transform Barbuda’s 62 square miles into a haven for luxury hotels and sprawling estates for billionaires, all the while dismissing strong opposition from locals and violating basic human rights protected by the Escazú Agreement and international law -- including Barbudans’ right to have a say in decisions affecting their lives and lands.

Since the time of slavery under British colonial rule, Barbudans and Antiguans have lived very differently. While Antigua’s economy is fueled by large-scale tourism, like most of the Caribbean, all land in Barbuda is “owned in common by the people of Barbuda,” and “no land in Barbuda [can] be sold” – a centuries old system formally recognized in these words of the Barbuda Land Act of 2007. Barbudan culture and identity is intimately tied to the land. Barbudans steward their dry, limestone island in balance with its delicate ecology: harvesting lobster, hunting, implementing slash and burn farming techniques and allowing select eco-tourism projects through its local governance mechanism, the Barbuda Council.

After Hurricane Irma hit in September 2017, the central government evacuated all 1,800 Barbuans to Antigua. It was necessary, they said, because a second storm was imminent. When no storm arrived, armed military personnel continued to seek out and remove those who wished to remain and rebuild. Barbudans remained on Antigua for several months, while their possessions rotted from the salt and sun.

Within days of the evacuation, developers and construction crews arrived and began round-the-clock work on an international airport a third of the size of New York’s LaGuardia, without any environmental assessment. “That’s when we realized that the government wasn’t interested in having Barbudans back,” told us John Mussington, an activist and Principal of Barbuda’s secondary school, “they wanted to redevelop the island as a private real estate venture.

This is the second feature of Barbuda’s story that encapsulates future challenges for human rights in the climate crisis. As Naomi Klein has written, this is disaster capitalism for the twenty-first century: the use of a crisis and military force to enact economic reforms that would not have been possible under normal circumstances.

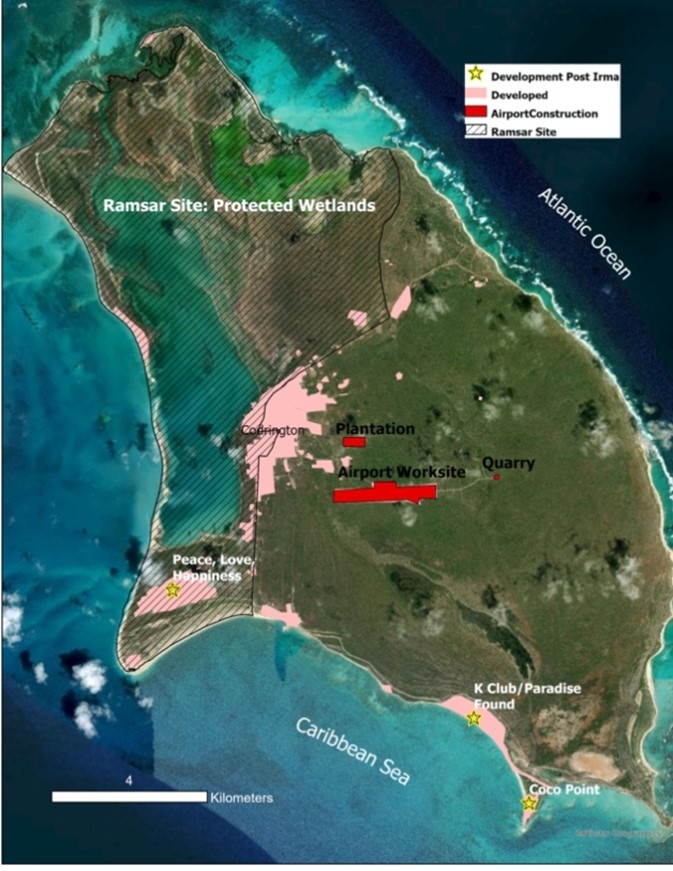

Within months of the hurricane, the government summarily repealed the communal land protections of the 2007 Barbuda Land Act. The scope of the development since then is striking, especially given pending legal challenges to this repeal and to several individual projects. Much of the development is inside Codrington Lagoon National Park, a wetland protected under the Ramsar Convention. As the below map shows, the projects cover most of the island’s Caribbean side.

(Figure 1: Developer’s map of planned projects / Source: Uknown; Figure 2: Map of projects currently in process and Ramsar protected areas / Source: Dr. Rebecca Boger)

One development is “Peace, Love and Happiness,” funded by American business magnates Steve Anderson and Jean Paul DeJoria. This project alone, for which construction is well underway, covers 650 acres of the National Park, nearly 2% of the island. The proposal includes around 500 homes, golf courses and a marina within the Codrington Lagoon to harbor the mega-yachts of the rich.

Meanwhile, the central government has extended little peace, love and happiness to Barbudans. “Those who may intend to become economic terrorists in this country, they would have to face the full extent of the law for any infractions whatsoever,” said PM Browne in 2015. This is how he referred to those opposing his plans for the “Disneyfication of Barbuda,” as environmental anthropologist Sophia Perdirakis called the reforms in a webinar organized by the Climate Litigation Accelerator at the New York University School of Law’s Center for Human Rights and Global Justice. This is a remarkable contradiction for a government presenting itself as a champion of a treaty (Escazú) whose original contribution to international law is the protection of environmental defenders’ rights.

The contradiction has recently sharpened. In July 2020, after Barbuda's only member of parliament Trevor Walker attended a protest against PLH, PM Browne told the press “Anytime they do anything illegal over there I am sending the police and army … I rather fight them and resign than to turn a blind eye.” In September 2020, at another peaceful protest against PLH, two Barbudan Council Members were arrested and charged with trespass and breaking COVID rules for not wearing facemasks.

The third warning Barbuda offers for the future is the following: just as the climate crisis presents an existential threat to human rights, human rights violations open the door to environmental deterioration and further global warming. According to the Global Coral Reef Alliance, the projects in Barbuda “will cause significant, and probably irreversible, deterioration of water quality in Codrington Lagoon, Barbuda’s major fish nursery ground.” The golf courses, resorts and houses will consume land essential for farming, animal breeding and pasture, and protected species. The developments need vast amounts of fresh water, requiring large-scale desalinization, a process that generates a toxic sludge that can seriously damage coral and sea life. Replacing mangroves, sedges and wetlands with shore-line structures will drastically weaken Barbuda’s resilience to sea level rise and other extreme weather events that will intensify yearly, as the 2020 hurricane season laid bare.

Today, Barbuda’s past and future identity hang in the balance. If the government is to take seriously its proffered commitment to international human rights, the environment and future generations, it needs to respect “communal land rights and conserve Barbuda's heritage, culture and environment,” as the Barbuda Silent No More movement has demanded.

The rest of the world should be paying close attention. Barbuda's fate, for better or for worse, will be evenly distributed across the world before too long.

*Co-authored with Elizabeth Donger, MPP, who is a student at NYU Law. Her non-profit work and scholarship focuses on climate justice, migration policy and child protection. You can follow her at @elizdonger.

For human rights to have a future, we must consider time

If the late 20th and early 21st centuries were a period of concern about space, I believe that time will be the most dominant variable in the remainder of this century, both in human rights as in other fields of practice and thought.

Globalization was a spatial phenomenon by definition: the expansion of markets across the world, the connection of the last corners of the globe to telecommunication networks, and the transnational rise of neoliberalism. Although the human rights movement was one of the sources of criticism and resistance against the inequities of globalization, it remained more focused on space than time. It concentrated on the global dissemination of human rights standards embodied in treaties and agreements, which became part of the language and common sense of global governance. Obsessed with going beyond the barriers of space, we—human rights analysts and activists—left aside the concern about time, as if globalization was effectively the “end of history” proclaimed by Fukuyama.

Today we know this was a hasty diagnosis not only because nationalism is building up walls of hatred around the world, but also because our disdain for time is taking its toll. If more evidence was needed that history did not end with the victory of liberalism and human rights, the recent elections results that consolidated illiberal democracies from India to Brazil are proof enough.

The time to cope with the climate crisis with conventional measures has also passed. My generation (X) was a product of globalization and it wasted the 30 crucial years it had to take gradual steps against global heating. Today generation Z teenagers go on school strikes to remind us of what scientists from the UN intergovernmental panel on climate change concluded: to avoid the most catastrophic climate change scenarios and the subsequent human rights crisis, urgent measures that cut carbon emissions in half by 2030 at the latest are the only way out.

Read more:

Recovering time also means changing the way we think about it. When globalization was booming, the prevailing disciplines, from geography to political economy and international law, focused on space. Today it is necessary to learn from other fields that hold a fuller understanding of time, such as biology and geology, considering that they are more connected with temporal phenomena such as the evolution of species and the formation of climate.

As geologist Marcia Bjornerud recently wrote, “an acute consciousness of how the world is made by—indeed, made of—time" is what is required. This vision means practical changes based on “timeful” ideas and proposals as beautifully expressed by Bjornerud.

I suggest two examples of “timeful” ideas related to human rights. The first is to acknowledge the rights of future generations. As George Monbiot wrote, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights falls short when it states “all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” The Declaration considers only present generations because its provisions do not prevent them from leaving an uninhabitable planet to future generations. A missing article in international law should state that “every generation has an equal right to enjoy natural resources” as Monbiot suggests.

Another timeful proposal is the declaration of constitutional emergency to address the climate crisis and the consequent rights violations, just as emergencies are declared to allow for exceptional measures during economic crises or wars. Today we know that, unless we face climate change with the same urgency and scale that is required by a world war, global warming will cause an economic collapse much worse than the 1929 great depression and a death toll greater than that of both world wars combined.

For this reason, England and Ireland declared a constitutional emergency to face the effects of climate change and the massive loss of animals and plants. Other states should follow for those very same reasons.

These are ideas that are supported by social movements with an acute awareness of time: the wave of student strikes for the rights of future generations, and the series of rallies led by organizations like Extinction Rebellion to protest against inaction against climate change. While the former reminds us of the importance of long-term of thinking, the later underlines short-term action.

The human rights movement should learn from these other movements. Therefore, it has to refine its long-term goals as well as its short-term response capacity. In regard to the first, thinking ahead of long-term trends is one of the blind spots of human rights players, like NGOs and philanthropic donors. We are habituated with one- to three-year planning and funding cycles, often failing to anticipate fundamental changes that require preparations now, but that will take place within ten to twenty years. An example is the deep changes in concepts and practice in human rights that will come about as a result of new technologies, like artificial intelligence and gene editing.

At the same time, human rights actors struggle to react with the necessary urgency in the short term. Human rights organizations have been more likely to give sluggish responses to existential challenges, such as the dissemination of authoritarian populism or climate change, possibly as a result of the inertia of conventional strategies. For instance, naming and shaming states that violate human rights are strategies that no longer work as before in a world of shameless populist leaders. Nor do they work in a fast-paced world where some of the most serious threats to human rights do not come from states but from private corporations, whose social platforms can help destabilize electoral processes in a matter of days.

If the human rights movement hopes to have a future, it will have to take time seriously.