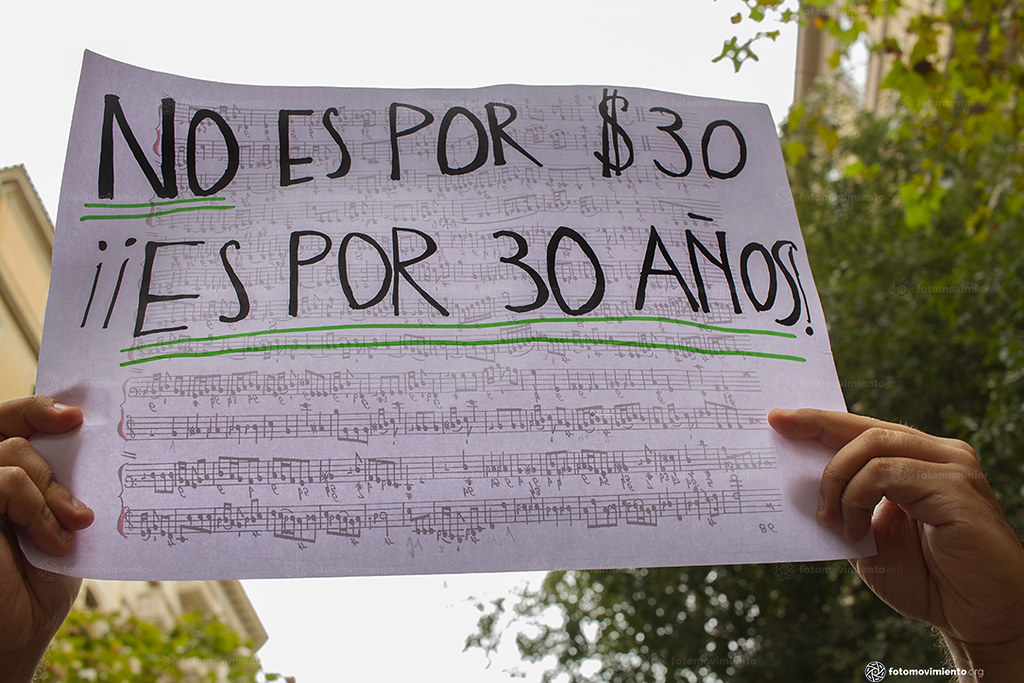

Photo: Fotomovimiento/Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

“It’s not about 30 pesos, it’s about dignity.” These were the words written on one of the many signs protesters have held high during the last weeks in the streets of Santiago, the capital city of Chile. What it means is that the nation-wide social movement of massive protests goes far beyond what actually lit the fuse – a fare hike of thirty pesos (0.04 USD) for the subway. Rather, the protests, some of which have turned into violence and looting, stand as an indictment of the fiercely neoliberal socio-economic model Chile has implemented for the past 40 years, since the times of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

But the Chileans are not alone. This year, massive numbers of people have inundated the streets of Hong Kong, Barcelona, Port-au-Prince, Baghdad, and Beirut. And beyond that, the 2010s will probably go down in history as one of the most politically agitated decades on record, including the Arab Spring, students protests, also in Chile, the “Indignados” and “Occupy Wall Street” movements in Madrid and New York, respectively, and the “Gilets Jaunes” in Paris, to name just a few prominent examples.

Is there a common theme across all these movements, despite their varied geographical locations and their seemingly disconnected timing? Again, the sign from the streets of Santiago provides a useful guide. If one had to narrow down the plethora of vindications across all these social movements to a single idea, one concept stands out: human dignity.

Indeed, it is arguably out of an enhanced sense of their own dignity that students, drivers, consumers, subjects, and citizens in general, have turned to the streets to demand a fair treatment of their legitimate interests, rights and aspirations. Yet, what is meant by a demand for dignity? Is it possible to define a more precise concept of human dignity, that would indeed unite the many demands set forth by these varied movements?

The nation-wide social movement of massive protests goes far beyond what actually lit the fuse – a fare hike of thirty pesos (0.04 USD) for the subway.

There is not a unique, clear-cut concept of human dignity in philosophy – or in the law. Indeed, human dignity has been characterized as what philosophers call an “essentially contested concept,”. That is, a concept that has many different definitions that compete among each other to provide the best and strongest account of the underlying core idea. Other examples of such essentially contested concepts are “democracy” and “justice”.

Actually, there are at least three strands of the idea of human dignity that may or may not work together in practice, although they are not necessarily incompatible in theory. The “autonomy” conception that postulates the dignity of every rational agent – most famously fostered by Immanuel Kant; the “welfare” conception – having to do with decent and sufficient material life conditions, which the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has called a “dignified existence”; and the “rank” conception – developed mainly by Jeremy Waldron during the past decade, according to which dignity is a legal status similar to aristocracy, only expanded now as a sort of “universal nobility” warranting legal recognition and respect for every single human being.

Across all these social movements, one concept stands out: human dignity.

Indeed, according to the rank conception, ever since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was proclaimed in 1948, the privileges, rights, and duties formerly reserved for aristocracy were universalized for every human being. They include the right to life and bodily integrity, the right to a fair trial, and the right to take part in the conduction of the polity as a citizen.

Turning back to the streets of Santiago – where protesters have even re-christened their main gathering venue as “Dignity Square” (“Plaza de la Dignidad”) – we may ask ourselves which conception of human dignity is being fought for? Is it a call for more individual autonomy? To a certain extent it is, since, although it is a mass movement, it is concerned with the so-called “rights language,” one of the most hard-won victories of individualistic liberalism in the past centuries. Does it belong to the welfare conception of human dignity? Most likely, as the demands of Chileans include such items as a reduced fare for transportation, better healthcare and pensions for the retired, and a lower cost of living more generally.

Could the Chilean demand for dignity refer also to the rank conception of human dignity? Possibly. The rank conception is strongly connected with the ability of a group to govern itself as a union of free and equal citizens, and that is accomplished primarily through a constitution of the body politic. In this regard, another item in the Chilean protests is the demand for a deep overhaul of the entire political system by way of enacting a new constitution that overcomes the one inherited by Pinochet in 1980.

In the end, it seems as though the three competing conceptions of dignity are combined in the Chilean social revolution of 2019. The welfare conception is probably most evident, whereas the autonomy conception is present inasmuch as it is a very vocal, rights-driven movement, and the rank conception is yet to unfold its full potential.

But at present, it is hard to tell where the Chilean struggle for dignity is headed – just as hard as it is with the rest of the world. For other latitudes, each protagonist must ask themselves what kind of dignity they are striving for. What is clear, however, is that this concept of dignity, even though contested, seems central to contemporary struggles and protest.