The explosion of protests following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police was a potent indicator that structural violence, particularly for people of color, goes far beyond racist policing. Cities are on the front lines of some of the most urgent social challenges we face: inadequate housing, an aging basic services infrastructure, unequal access to health care, struggling schools, and continued segregation.

An increasing number of cities are turning to human rights instruments, in particular as articulated through the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as means to address such systemic failings. Yet typically, human rights norms are conceptualized as universally applicable, and as such, have been criticized for being too abstract or detached from concrete, local realities to be useful. However, universalism and localism can fruitfully be seen as interconnected elements of a process of social transformation. We know that law alone is not enough to protect rights, but international human rights provide a set of foundational norms that local actors engage in an “ongoing experiment” of transformation.

Cities are on the front lines of some of the most urgent social challenges we face.

The transformational potential of “SDG cities” to advance global human rights norms is dependent upon their ability to transcend surface-level solutions and attack the structural and cultural roots of injustice. Obviously, this is easier said than done.

A useful tool for unpacking this process is the “MAPs” (mechanisms, actors, and pathways) framework, which draws attention to actors at global, regional, and local levels who utilize both generalized and targeted mechanisms to forge pathways toward rights realization. The MAPs framework calls our attention to which actors, with what beliefs and perspectives, are taking which actions (and incentivized how), toward what kind of social transformation. This latter question is crucial: “human rights” as individual claims may stop short of addressing the structural and cultural underpinnings that could truly transform society. Yet, they also imply (and sometimes explicitly demand in the form of state obligations) examination of the structural and systemic factors that facilitate or thwart rights realization. This is where the radical potential of human rights lies.

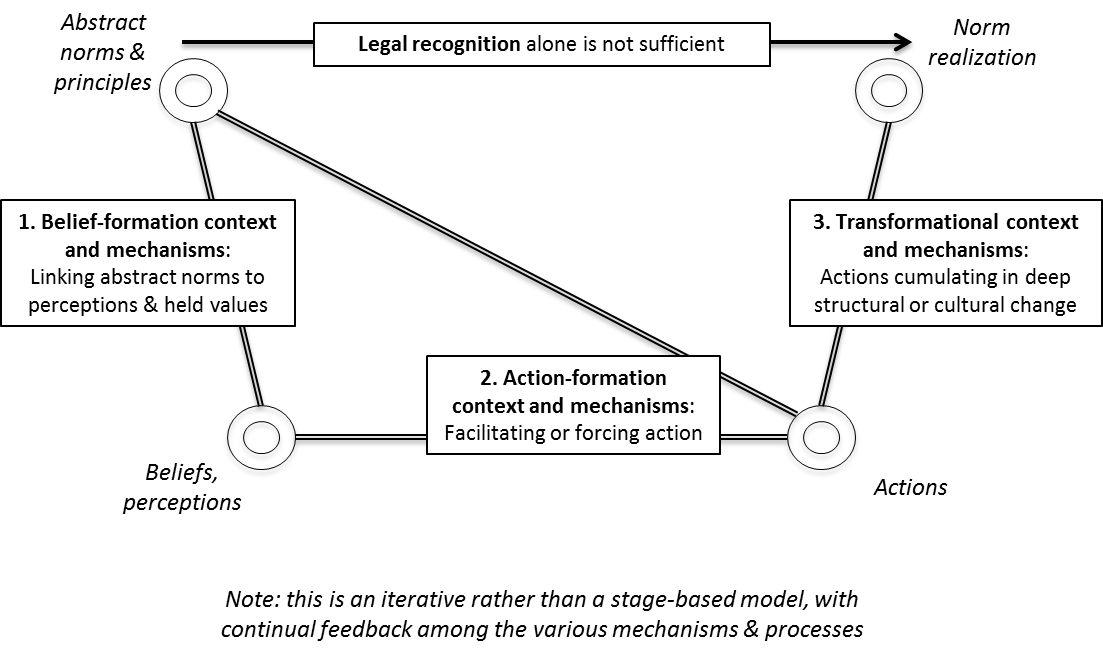

As Figure 1 illustrates, in the first “moment of social transformation,” prevailing structural and cultural realities, as well as “belief formation” processes shape actors’ beliefs and perceptions. The second moment is when desires and beliefs translate into action – or, in the absence of particular beliefs or perceptions, incentives or coercion compel action. The third moment is the culmination of actions and interactions into broader structural and/or cultural change, setting the stage for new beliefs and perceptions to emerge.

Figure 1. Moments of social transformation (Haglund and Stryker, 2015)

Operating at each of the analytic “moments” (1-3) above are multiple mechanisms through which change can occur: informational (data and indicators, shadow reports, monitoring), symbolic (framing, meaning-making – visual or imagined), power-based (protest, international pressure), legal (international, national, or local), and cooperative (community building, alliances, shared projects). This framework illuminates pathways by which local action can support transformation.

Local governments have taken some promising steps to implement the SDGs. Planning, reporting, and voluntary local review integrating SDG goals and benchmarks, for example, provide new ways to understand and monitor progress, raise awareness of where action is needed, and provide roadmaps for action. They also provide opportunities for sharing and comparison among cities. Inclusion of community-based organizations and civil society in these plans and reports allows for more robust flows of information and monitoring, shapes community feelings of efficacy, creates linkages among the multiple issues facing cities, and builds alliances for deeper change. Institutionalizing human rights in local policy decisions can further strengthen accountability to the SDGs in the absence of binding obligations. Coalitions such as the US National Human Rights Cities Alliance mobilizes a range of mechanisms – data gathering, reporting, organizing, and pressure on public administrators – to do just that.

The SDGs cities movement can learn from similar efforts to ensure a “Right to the City.” At its most general, a Right to the City calls for burdens, benefits, and decisions that affect city life to be shared equally among inhabitants. At its fullest, it implies a radical reconfiguration of the underlying political economy. Unfortunately, the rhetoric of “the right to the city” has been adopted and coopted in ways that not only do not challenge neoliberal governance but actually attempt to erase any such challenges. At Habitat III in 2016, for example, the “New Urban Agenda” (NUA) and “right to the city” discourses were bandied about by entities like development banks, the US State Department, and individuals like President and CEO of Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation who warned, without embarrassment, that NUA policies found to displease financiers will be ignored or the economy will suffer. Indeed, elite interests can easily co-opt the counter-hegemonic banner of “a right to the city.”

There is ample reason to be skeptical of the radically transformative potential in fora such as these. In my own research, the use of rights discourses by middle class resident welfare associations in Delhi to call for the eviction of poorer communities illustrates the tensions. The essentializing of “urban inhabitants” as somehow sharing a destiny ignores inequalities among inhabitants that may require more fundamental restructuring to overcome. Cities are as susceptible to reifying social divides under a false unity as are universal human rights.

Cities do not belong to everyone equally; law and policy can be wielded by powerful actors in defense of the status quo. The SDG Cities movement bears the same risk of becoming another hegemonic project of reimagining the city without rooting out structural and cultural barriers to rights realization. Thus, transformative change may mean challenging the underlying economic model, property rights, power relations, and/or longstanding elite privilege. It also means overcoming backlash – xenophobia, racism, and jingoism – which manifest not only nationally and globally but also locally. To do so, achieving urban human rights must be seen as a process of social transformation, where visions beyond profit, interests beyond elites, and actions beyond growth and job creation are valorized and vested with power.

This piece is part of a series published in partnership with Occidental College’s Young Initiative on the Global Political Economy, division of Social Sciences at Arizona State University, and USC’s Institute on Inequalities in Global Health. It flows out of a September 2019 workshop held at Occidental on “Cross-cutting Global Conversations on Human Rights: Interdisciplinarity, Intersectionality, and Indivisibility