If Virginia Woolf needed a room of her own to write fiction (and much more), Paula needs a place to call home to live her life and to raise her kids. But ineffective policies are blocking her at every turn. Paula is just one of thousands of women who cannot escape the trap of insecure housing after going through an eviction in Spain.

More than 30,000 households were evicted from their rented homes last year alone.

More than 30,000 households were evicted from their rented homes last year alone, as in the previous one, and the one before. The number of households evicted from mortgaged properties does not fall far behind.

Going through an eviction is a traumatic experience for everyone, but Amnesty International has documented that women often experience it differently—and more frequently. Women are overrepresented in part-time jobs, find themselves at the lower end of the pay gap, and regularly bear domestic care duties. Single-parent families, which are predominantly headed by women (in more than eight out of ten cases), often live in rental accommodations. Official statistics show that these families also face higher than average rates of poverty, social exclusion and material deprivation.

Amnesty International interviewed 19 women and four men who either have gone through an eviction or are at risk of being evicted. At least seven of them complained that the judge had not enquired about their personal circumstances. “We did not get the chance to explain our situation to the judge,” said Ana. A female judge in Barcelona confirmed this problem, saying: “When we receive the eviction suit, we have absolutely no idea who lives there.”

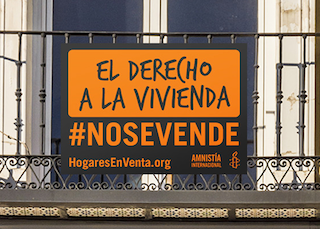

Amnesty International 2017 (All rights reserved)

Despite some optimistic market and macroeconomic projections, the housing rights crisis in Spain is far from over.

Paula, a single mother of three and a survivor of gender-based violence, was evicted from a social apartment sold in 2013 by the Regional Housing Authority of Madrid to an investment trust, alongside nearly 3000 other properties. Relying on unstable part time work, bills piled up and Paula could not keep up with payments. It was not long before she received the eviction order. “My daughter left a note asking the new tenants to let us stay. My five-year-old son still asks when we are going back home.” At the time of this writing, Paula and her family are still waiting for an alternative housing solution from public authorities in Madrid.

Most women interviewed by Amnesty International reported that social services recommended people facing an eviction, including those with children, to move in with their parents, relatives or friends. Municipal social workers explained to us that this was necessary due to insufficient resources made available to them. Sometimes social services may recommend people to look for and rent a room in the private market, offering to cover the costs. However, this is not always a feasible alternative for single mothers and women with care responsibilities, and it is not adequate for children either.

.png)

Amnesty International 2017 (All rights reserved)

Given the largely insufficient public housing stock, even survivors of gender-based violence that are granted a restraining order are forced to wait for a long time without assurances.

Survivors of gender-based violence are even more exposed to the consequences of uncoordinated and poorly resourced housing policies and social services. Whilst the 2004 Comprehensive Law on Gender-Based Violence established that survivors should be treated as a priority group to access social housing, authorities in the Region of Madrid make this conditional upon a court conviction or a restraining order. This effectively means that most survivors of gender-based violence do not get the necessary support to satisfy their right to housing. It is encouraging to see that, only three weeks after the publication of Amnesty International’s report, the Government of the Region of Madrid has announced its intention to put an end to this restrictive policy. That said, given the largely insufficient public housing stock, even survivors of gender-based violence that are granted a restraining order are forced to wait for a long time without assurances, as in the case of Paula. What is supposed to be a protective measure becomes no more than an empty promise.

Housing is clearly not a priority for Spanish authorities. Spain’s central/federal public spending on housing and community amenities lies well below that of most OECD countries. The 2016 federal budget on access to housing and support for housing renovation was €587 million, less than 37% of the €1.6 billion allocated in 2009. The 2017 proposed budget, soon to be formally approved in Parliament, reduces the allocation 20% more. Even considering the severe austerity imposed in the county, no other budget item experienced such a significant reduction during the economic crisis. In no other OECD-member country have house prices outpaced income as much as in Spain. Spain is also the EU Member State with the highest growth in personal housing expenditure in the last decade.

Despite some optimistic market and macroeconomic projections, the housing rights crisis in Spain is far from over. With the exceptions of the Basque Country and the Region of Valencia, Spanish laws do not recognize that housing is a human right. Existing policies both at the federal and the regional levels clearly lack the necessary gender perspective to address the structural inequalities too many women fight with every day. This would entail higher investment in social housing but also, among other things, requiring judges to assess the proportionality of an eviction on a case-by-case basis, and providing a comprehensive response to survivors of gender-based violence, in line with the Istanbul Convention of the Council of Europe.

Put bluntly, human rights are not worth the paper they are written on when thousands of women, men and children lack a place to call home.

**Koldo Casla authored Amnesty International’s "The housing crisis is not over" report.