Earlier on openGlobalRights, several authors noted both the tensions and the potential collaboration between Islam and human rights (see here, here, and here). These observations, however, apply just as easily to the other monotheistic religions, Judaism and Christianity. Followers of these creeds vary in their attitudes towards universal rights, and these differences stem from historical upheavals in relations between religious institutions and the state.

Clear differences in human rights practices across Islamic countries show that what matters is not religion itself, but rather religion’s social carrier, religious thought and interpretation.

Religious thought refers to varying interpretations of scripture and to their practical application. Interpretations of human rights principles in Saudi Arabia, for example, differ substantially from those found in Iran, Malaysia, Afghanistan and other Islamic countries. There are also variations between various political Islam movements. Waqf (Endowment) for the Muslim Brotherhood (MB), for example, is different from the waqf for Hizb ut-Tahrir (Party of Liberation) and other Salafist and Jihadist movements.

Christian Fanz Tragni/Demotix (All rights reserved)

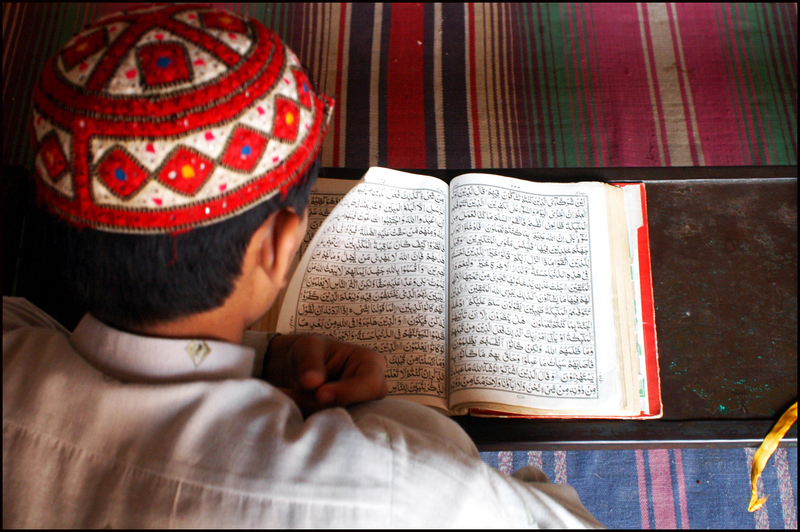

A Koranic school in Pakistan.

Religious values are popularly considered the principal source of human rights principles and values. As others have noted on openGlobalRights (see here, and here), many religious values seek to foster justice and equality. As a result, the names of many religion-based political parties in Islamic countries include the words “justice” and “equality”.

Yet while scripture is fixed, it varies in its relationship to human rights. These variations are governed by the method one uses to read and interpret the holy texts. Some interpret scripture a-historically, while others interpret argumentatively, in light of current belief in human rights. Tolerant, critical and historical readings of scripture can bring these texts closer to contemporary universal human rights principles.

This is true for all issues, including those surrounding the role of the state, freedom of opinion, expression, and belief.

Political Islam movements and many educated religious elites insist that Islam differs from other religions in that it is both a religion and lifestyle. It is concerned, they say, not only with spiritual matters that prepare Muslims for their journey from worldly life to the eternal afterlife, but also with human affairs during their life, including morality, relationships, deeds, and, most importantly, the state’s identity.

Drawing on this expansive interpretation, many Islamic countries are becoming more religious, limiting personal freedoms in the name of Islam.

This is even true in my own country, Palestine. Our Basic Law, for example, which was drafted in June 2000, states, “Islam is the official religion in Palestine,” although it also acknowledges that “all other monotheistic religions are accorded sanctity and respect.” The Palestinian Basic law also states that “The principles of the Islamic Shari’a are a main source for legislation,” a formulation common to many Arab and Islamic constitutions.

This insistence on giving the state a religious label contradicts modern notion of states that are equally accessible to all nationals, in which all citizens enjoy the same rights and have the same duties. The modern state is a state for all its citizens, Muslims and non-Muslims, believers and non-believers. The same applies to the political executive, who is no longer the Emir of the believers only, and to the nation, which does not belong only to believers.

A rights-respecting state must be tolerant and secular, treating everyone equally regardless of religious or political affiliation. Half-hearted phrases, such as “according sanctity and respect,” but not full equality, to other religions, are not sufficient.

Women’s rights are another important sticking point.

Human rights charters stress the need for complete equality between men and women, but Islamic legislation discriminates with respect to women’s right to inherit, play a formal role in courts of law, and more. In these and other instances, Muslim men often enjoy more powers and rights than Muslim women.

While scripture is fixed, it varies in its relationship to human rights

Traditional Islamic preachers encourage fixed, conservative interpretations of Shari’a, perpetuating patriarchal cultures. Traditional thought defends discriminatory behavior not as bias for men, but as a way of “honoring” women and saddling men with special, more onerous duties.

As a result, divorce in many Islamic countries is essentially in male hands. Muslim men may marry women of other faiths, moreover, whereas Muslim women usually cannot. In many states, moreover, women need consent from a male “guardian” to travel or make major life decisions, and their share of an inheritance is half that of a man’s.

In many Islamic countries, moreover - especially those that are Arab - the state bars women from political leadership roles. In Saudi Arabia, women cannot even drive.

Yet as Fitzgibbon et. al. write for openGlobalRights, it is “politics and culture,”not Islam itself, that drives these human rights violations.

Consider political leadership. One dominant Arab-Islamic school of thought refuses to permit women to assume wilaya, or political authority. Other conservative Islamic countries, however, including Pakistan and Bangladesh, find it entirely appropriate for women to run for elected office. Culture and interpretation of scripture, in this case, are more important than Islam, per se.

Consider also freedom of creed. In most Islamic countries, Muslims are legally barred from embracing other religions or becoming atheists. This, in Islam, is called apostasy.

Historically, major Islamic leaders, such as the first Caliph after the Prophet, Abu Bakr as-Siddiq, were bitter opponents of the apostates. As a result, many Islamic schools of thought still regard the death penalty as an appropriate punishment, and in much of the Islamic world, conversion to Islam is celebrated, while the reverse is not tolerated. Some Islamic scholars argue about the freedom of a person to believe or not, but debates against apostasy itself are rare.

Aligning Islamic thought with human rights principles requires a tolerant reading of the scripture so that there is neither eclecticism nor authority. Egyptian trade unionist and author, the late Jamal al-Banna, was a brother of the founder of Muslim Brotherhood, but criticized traditions that are contradictory to the Quran’s message of tolerance and freedom. He also held that no specific verse obliges women to wear veils, and only suggest modesty. Rashid al-Ghannoushi, exiled leader of the now-banned Tunisian Islamist movement Al-Nahda, and theorist for Hamas challenges other Islamists when he says Islam accepts multi-party democracy. They have shown that moderate, liberal interpretations of scripture are possible.

Interpretation is thus the door to an open or shut society, determining not only the nature of religious practice but also politics and human rights.