I recently attended two academic workshops where participants expressed serious reservations about local human rights struggles. They seemed to associate local rights praxis with the growing global backlash against international human rights norms and institutions—adding to already significant worries about the future relevance of human rights in a world marked by metastatic inequality. The backlash is real, but it’s a mistake to imagine all local struggles as repudiations of human rights.

The mistake is commonplace, because most human rights advocates conceive of them as cosmopolitan—that is, as transcendent, universal, liberal, and international. Anything local is suspicious by default. This conception of rights is built on bad history and bad philosophy, as many communitarians and post-colonial critics have argued in rejecting them. These critiques, too, treat rights as inherently cosmopolitan. It’s time to forget cosmopolitanism: it’s flawed and it impedes clearheaded analysis of backlash. The future of human rights (like their past) is local.

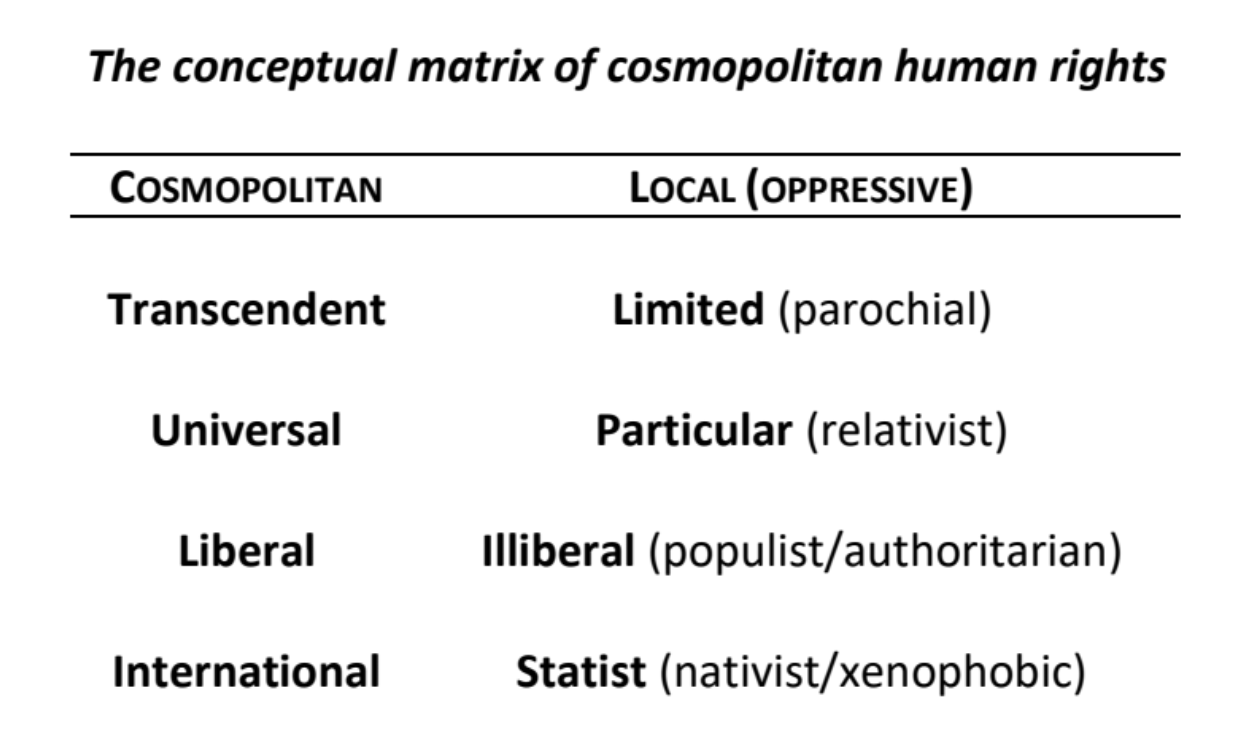

Cosmopolitanism configures human rights in opposition to the local, the specificity of which represents an ethico-political geography anathema to rights advocates.

In this conceptual matrix, the local comprises the various aspects of oppression that human rights are supposed to overcome. Transcendent rights vanquish local parochialism. Universalism trumps particular moralities. Liberalism provides a bulwark against populism and authoritarianism. International norms and institutions check and restrain recalcitrant states.

On this widely held view, it’s easy to see why the local is automatically suspicious in the eyes of cosmopolitan human rights advocates. However laudable the goals, tactics, and aspirations of local struggles might be, they always embody a latent contradiction and pose an implicit threat. Put differently, they amount to backlash—even if in spite of themselves.

To be clear, I am not suggesting that most scholars or practitioners oppose or condemn local human rights struggles. My colleagues at those workshops were sympathetic to, even enthusiastic about, the local work that I was discussing. My point is that the dominant cosmopolitan framework of human rights thematizes the legitimacy of local struggles almost by default.

This framework rests on bad history and bad philosophy and leads to bad analysis and bad politics. For a long time (and still today) the standard history of human rights was one of Progress, the slow but seemingly foreordained development of Enlightenment ideals through imperfect philosophical and political achievements culminating in the Universal Declaration of 1948 and its associated legal and institutional machinery. This history is doubly wrong: it ignores how “cosmopolitan” rights have been constructed through and enlisted in colonialist and imperialist projects old and new. At the same time, it ignores centuries of local struggles for rights, dignity, and equality that often sought radical social and economic reform and often manifested in anti- and de-colonial struggles.

Bad history and bad philosophy generate bad analysis and bad politics.

Philosophers have abetted bad history with bad ethics, depicting rights as universal principles that trump particularistic claims. Relativism—the horrific possibility that people might hold varied and sometimes conflicting views about ethics—presents the paramount moral threat to human rights. Ironically, the supposed foundation and contents of supposedly universal rights are continually being reformulated—Natural Law, Reason, autonomy, dignity, consensus—though always within a liberal framework. The actual social construction and contestation of rights is routinely ignored or spun into a fairy-tale of the “progressive unfolding” of universal truths. Meanwhile, transcendent liberal universalism provides a justification for international human rights laws and mechanisms, including tribunals and “humanitarian” interventions, that only perpetuate legitimate fears of human rights imperialism.

Bad history and bad philosophy generate bad analysis and bad politics. Growing anxiety about a backlash against human rights conjures images of populist strongmen spouting racist or nativist ideologies and spurning the shared norms and noble architecture of the liberal world order – of the outright rejection of cosmopolitanism. There are real worries about authoritarian nationalism, obviously, but knee-jerk defenses of cosmopolitanism obscure that the “liberal world order” has always been a myth. Much populist outrage originates in reasonable frustration with the liberal democracy and neoliberal economics espoused by virtually all major political parties. The resulting facile treatment of populist and anti-globalization movements as threats to human rights forecloses the radical democratic and economic possibilities that many local rights struggles prefigure.

Local rights movements, it’s true, are typically not cosmopolitan. They prize local autonomy and make situated, specific, and contextual demands. They insist on democratic control and propose new rights and new understandings of rights; many are wary of international human rights actors. Yet they are not parochial, relativistic, illiberal, or statist. Many use global analytic frameworks, embrace shared values, comprise diverse coalitions, and work trans-locally in solidarity with other movements in global networks that promote multi-directional learning and engender creativity and innovation through the sharing of knowledge and resources. In short, many local human rights struggles embrace a people-centered approach to human rights that defies the binary oppositions in which cosmopolitanism is rooted.

Struggles for the right to the city are a great example. They connect local injustice to global structural problems. They insist on familiar civil and politics rights while making transformative demands for everything from public transit to the de-commodification of housing and democratic alternatives to corporate power within an expansive human rights frame. They seek community-based strategies for realizing rights, including the creation or development of local human rights institutions, even as they engage imaginatively with international human rights machinery. Without question, they show that anti-cosmopolitan backlash does not entail the rejection of human rights.

Forget cosmopolitanism; it’s riddled with problems and gets in the way of understanding the most exciting human rights activism in the world today. The future of human rights is local.

This piece is part of a series published in partnership with Occidental College’s Young Initiative on the Global Political Economy, the division of Social Sciences at Arizona State University, and USC’s Institute on Inequalities in Global Health. It flows out of a September 2019 workshop held at Occidental on “Cross-cutting Global Conversations on Human Rights: Interdisciplinarity, Intersectionality, and Indivisibility.