Human rights and religion need each other. Although the universality of human rights may require a secular presentation, the human rights movement’s real power comes from its inherent religious dimensions. When today’s human rights activists recognize and connect with those dimensions, they gain strength, new alliances, and the greater global legitimacy they so urgently need.

As preliminary evidence, remember that so many of the world’s struggles for freedom and dignity were led by people of deep faith, including El Salvador’s Oscar Romero, India’s Mahatma Gandhi, Iran’s Shirin Ebadi, the United States’ (US) Martin Luther King, and Burma/Myanmar’s Aung San Suu Kyi.

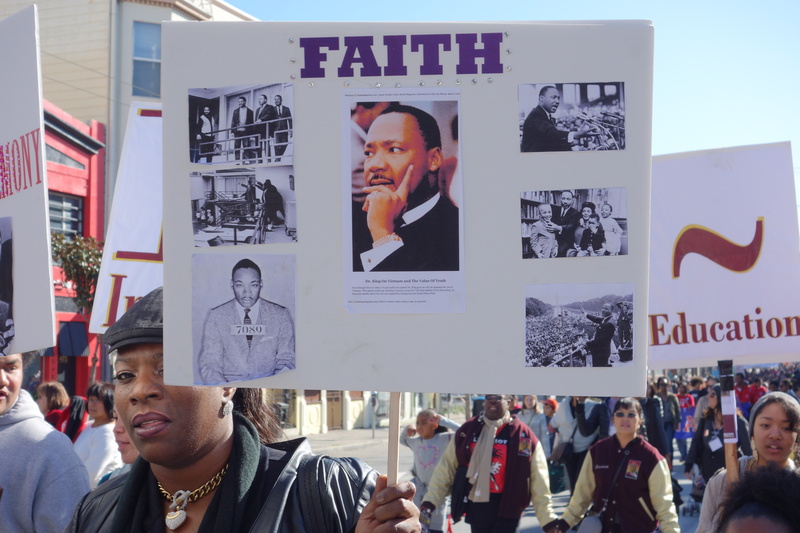

A woman carries a sign with photos on the march to honor Martin Luther King Jr (San Francisco, 2013). Steve Rhodes/Demotix All Rights Reserved.

These and other believers have been disproportionately active in movements for rights and social justice. They do so because their faith often gives them the moral inspiration, the popular legitimacy, and the internal strength to endure great suffering. As a result, faith-based action has been, and still is, one of the most important forces undermining repressive political systems everywhere.

Religions and rights often converge because of a shared belief in what the Universal Declaration of Human Rights calls “the inherent dignity” of “all members of the human family.” Like the Declaration, most religions preach a love of all human beings, and the need for action when human dignity is violated.

Human rights and religions also share the claim that this dignity, along with the rights required to protect it, is not a human or government invention, but is rather present at birth in each and every one of us.

Given these affinities, it is both surprising and tragic that relations between religion and human rights - especially of late – are so often problematic.

From Northern Ireland to the Vatican, Syria, and Central African Republic, religious figures and interpretations are often boldface contributors to abuse. Defenders of unjust structures and behaviors often use religion to suppress courageous voices for change, create divisions, justify oppression, and violate rights of vulnerable people.

Indeed, some of the most spectacular expressions of religious fervor come from groups that promote violence, intolerance, misogyny and homophobia. In the US, for example, religious activism is often associated with attacks on the rights of women and LGBTQ people, scientific inquiry, and criticisms of unregulated capitalism.

As a result, the media and many scholars often ignore religions’ progressive expressions, viewing faith as an expression of superstition, fanaticism, or conservatism.

Many human rights advocates share this view, and stress the secular nature of human rights work. Among other things, they note that the Universal Declaration contains no reference to God or faith. The Declaration’s drafters did this intentionally, so as to enable the document’s acceptance by people of any, and no, religion.

As a result, many human rights proponents view secularity as key to the Declaration’s effectiveness. As the eminent legal scholar Louis Henkin put it, “The human rights ideology is a fully secular and rational ideology whose very promise of success as a universal ideology depends on its secularity and rationality.”

Human rights professionals, many of whom are lawyers in international or domestic NGOs, typically speak to other professionals in NGOs, government, and inter-governmental organizations.

Although the website of Human Rights Watch and other likeminded groups provides abundant examples of moral outrage, these are rarely linked to any attempt at social mobilization, including among faith communities. The tacit message is that pro-human rights action is best left to secular professionals, media watchdogs, and liberal governments or intergovernmental organizations.

The increasingly sharp divide between human rights professionals and religion comes at serious cost. By portraying human rights as something secular, legalistic, and owned by professionals, practitioners distance it from the multitudes whose action is needed to move governments.

To improve human rights, mass publics must get involved, including those whose rights are most violated. And yet, even victims of the worst abuses are unlikely to engage with a concept and with organizations that appear unrelated, or even hostile, to the religions that give them comfort, strength, meaning, and practical assistance.

Human rights groups are aware of the power of religion, but their attempts to connect with that power are remarkably limited. Consider Amnesty International USA, a civil society group built around the principle of mobilizing the public for action. Although it has many public outreach programs, all are aimed at students, professionals, lawyers, educators, and youth. Remarkably, not a single one is aimed at religious leaders or communities.

This lack of engagement with US religion is due not just to the distance between human rights and religious leaders, but also to human rights leaders’ distance from the inherent religious dimensions of their own ideas.

These religious dimensions of human rights do not depend on particular religious beliefs or views on the nature and existence of a God. As legal scholar Ronald Dworkin notes, religion is any worldview that “holds that inherent, objective value permeates everything, that the universe and its creatures are awe-inspiring, that human life has purpose and the universe order.”

Without saying why, the Universal Declaration asserts that every human being is born with the “objective value” of dignity and rights, and that these transcend the individual. This inherent dignity connects us with every other human being, and thus to the order and purpose of our world. Implicitly, this also connects human rights with virtually every religious tradition, including both those that believe in - and do not believe in – a theistic God.

More importantly, the people who fight for human rights often experience this inherent sense of connection. This personal, individual, and powerful experience gives human rights their full meaning and social power. This experience, felt by secular and religious activists alike, explains the courage of a student standing in front of a Chinese tank in Tiananmen Square, of a woman standing alone with the placard, “give women their rights” in a Saudi square, and of all those who courageously risked their lives for rights from El Salvador to South Africa and Tibet.

It is important --vitally important--to translate the internal experience of rights into laws. If this legal translation denies this transcendent experience, however, those laws’ force and legitimacy is greatly diminished.

It is this loss, easier to see than to measure, that has contributed to the recent talk by British academic Stephen Hopgood of the “endtimes of human rights.”

This disconnect is also a great loss to religion. The power of faiths, which globally show no signs of diminishing, comes from the symbols, rituals, and texts that capture the transcendent and sacred reality people experience. We need human rights to protect the expression, and guard against the misuse, of this power.

As scholar Abdullahi An-Naim explains, human rights are also necessary to safeguard the rights of believers to challenge religious orthodoxy and attempts to identify religion with rights violators. By passing laws based on human rights, the state helps different religious communities, and members of the same community who have different interpretations, live together in shared political space. And by struggling to align their values with human rights standards, religions grow in ways essential to their vitality.

To get a sense of how religion and human rights have worked together, consider the US civil rights movement. As historians document, many of the people who fought for civil and constitutional rights in America thought of their movement as a religious event. The same is true today for the remarkable Moral Mondays Movement that mobilizes thousands every week to risk arrest and fight voter suppression, economic injustice and other violations in North Carolina.

In 2007, the transformative power of religion was on view in Burma/Myanmar, when thousands of Buddhist monks joined protests and withdrew spiritual services from military personnel. In 2010/11, religiously motivated activists beyond the Mulsim Brotherhood played key roles in the Arab Awakening. As Yale professor Seyla Benhabib notes, “Just as followers of Martin Luther King were educated in the black churches in the American South… so the crowds in Tunis, Egypt and elsewhere draw upon Islamic traditions of Shahada -- the act of being a martyr and witness of God at the same time.”

Sadly, the US, Myanmar and Middle Eastern countries also show how religious power, when untethered to human rights commitments, can turn demonic. Whether it is the American religious right that demonizes LGBT and other people, the Buddhist groups in Burma who kill Muslims, or the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt that used state power to attack democracy, the harm done by organizations in the name of religion is often horrific.

Combatting religious-based oppression is complex and urgent. Ultra-exclusivist religious groups often welcome secular criticism, portraying it as an attack on faith itself. As a result, some of the most effective work against religious-based oppression comes from human rights-minded co-religionists such as the Network of Engaged Buddhists, the Jewish T’ruah, the Christian Faith in Public Life, the Muslim Musawa, and many others.

Secular rights groups must support, protect and learn from these faith-based allies. Most importantly, secular rights workers must rediscover the faith and values they share with religions, and work together in movements that draw on the best of human rights and religions.

By reuniting faith and human rights worldwide, we can replace the approaching human rights “end times” with growth, renewal, and resurgence.