What happens online can have very real consequences offline. For some people, these consequences might seem minor, even though content is easily taken out of context or manipulated. But for human rights activists trying to claim freedom of expression and civic space, the risks are very serious and at times can be fatal. In April 2016, Nazimuddin Samad, a young Bangladeshi law student, who was known for expressing secular views online, was hacked and then shot to death by unknown assailants in Dhaka. Earlier, in 2013, his name had appeared on a hit list of 84 atheist bloggers published by a group of radical Islamists. Several other bloggers on the list had been killed already the year before. Unfortunately, this was not an isolated incident: in Bangladesh, Asia and the rest of the world, people are being harassed, threatened, arrested or killed for what they say or post online.

Across Asia, governments are realising the power of online spaces and are adopting policies and laws that effectively criminalise online dissent and expression.

Across Asia, governments are realising the power of online spaces and are adopting policies and laws that effectively criminalise online dissent and expression, as Thailand’s new “Computer-Related Crime Act (CCA)” demonstrates. The CCA was adopted on 16 December 2016, and gives broad powers to the government to restrict free speech, enforce surveillance and censorship, and retaliate against activists. For example, Articles 14(1) and (2) of the new law gives the government the ability to prosecute anything they designate as “false” and—in the case of article 14(1)—“distorted” information, vague terms which are easily abused.

Pixabay (Some rights reserved)

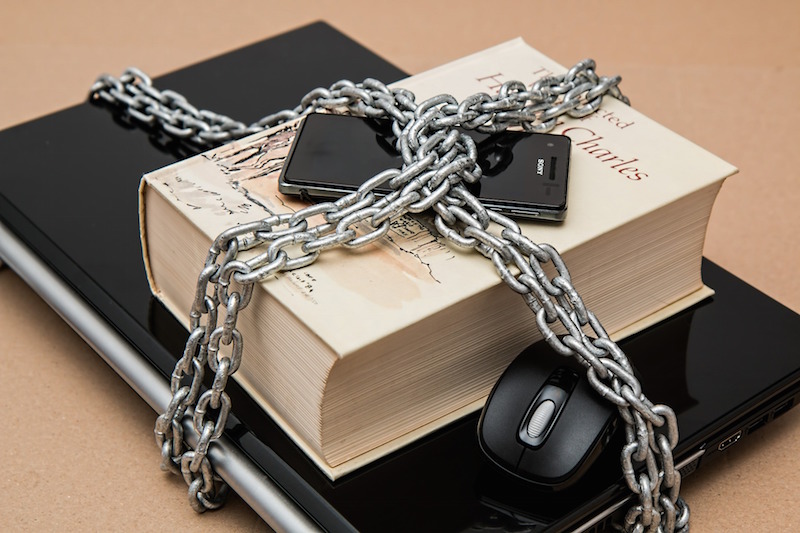

As we are in a battle for civic space in the real world, we also need to fight for our space online.

Internet use, nonetheless, is expanding exponentially. According to the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 15.8% of the global population had access to the Internet in 2005. By 2016 this had risen to 47.1%. For Asia Pacific, this number jumped from 9.4% in 2005 to 41.9% in 2016. Yet Freedom House reports that two-thirds of all Internet users (67%) live in countries where criticism of the government, military, or ruling family is subject to censorship. Of the countries in Asia included in the report, Myanmar, Thailand, Pakistan, Vietnam and China are ranked as “not free”.

Despite the different challenges in Asia, online spaces offer platforms for activists to circumvent the shrinking of civil society spaces that they face in their struggle to promote and protect human rights, and to speak out against governments or non-state actors. In recent years, social media has become particularly useful to organise and coordinate public protests and advocacy campaigns.

For example, Maria Chin Abdullah was arrested on 18 November 2016 and detained for 11 days, on the eve of a Bersih protest that called for governmental reform and transparency in Malaysia. From the moment she was arrested to the day she was released, her fellow human rights activists utilised online tools, especially Twitter, to campaign for her release. They even reached out directly to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, Maina Kiai, who responded by calling on the Malaysian Government through Twitter himself for Ms. Abdullah’s release.

Yet, cases such as these also reveal how our online devices, particularly those with GPS capability, make it increasingly easy for us to be tracked, traced and followed. Anything we post, even when deleted, remains online in some way or another forever. In several cases, governments are utilising this to their advantage for purposes of surveillance and tracking. In Singapore, for example, Roy Ngerng and Teo Soh Lung are currently under police investigation for allegedly breaching the election law by posting election-related content on their Facebook account the day before the polling on 6 May 2016, widely known as “Cooling-off Day”.

Another rising trend across Asia has been the misuse of social media to spread hate speech, distort facts, spread misinformation and in general spark a rise in sensationalism, extremism and polarising narratives. One prominent example is Malala Yousafzai, a Pakistani activist for female education and the youngest-ever Nobel Peace Prize laureate, who is generally heralded as inspirational, brave and heroic. However, in her own country of Pakistan views of her are a lot more complicated, in great part due to unjustified rumours and intentional misinformation spread about her online. Attitudes range from hostility about her special status to rumours that she is actually a CIA agent or that the assassination attempt on her life was a hoax. While she has many supporters in the West, Malala can never return to her home country due to death threats and general hostility towards her—much of which has been spread online.

Of course, in spite of the risks and challenges, online tools still present plenty of opportunities for the promotion and protection of human rights. To begin with, online tools and spaces have changed the way human rights defenders engage and collaborate with each other. We can share information almost immediately, mobilise a broad range of partners and supporters for our causes, and engage directly with key stakeholders. Online tools and spaces have also enhanced our ability to reach out to much wider audiences.

Online tools and spaces also help human rights defenders to keep stories alive, and to keep certain cases in the spotlight that might otherwise slip off the radar. One illustration of this is Sombath Somphone, a Laotion development worker who disappeared in Vientiane, Laos on 15 December 2012. His abduction was recorded by a police surveillance camera (CCTV), which shows that he was stopped by the police and taken away. The Lao authorities have denied they were involved in Sombath’s disappearance, claiming that the police are still investigating what happened to him. Even though it has been over four years since his disappearance, his story is still rippling across the world due to the work of the Sombath campaign, an effort made possible through online tools and spaces.

Now more than ever, we need to make sure we use online spaces safely and securely. Initiatives like Security-in-a-box, Bytes for All, Pakistan, Access Now, IFEX, EFF, Association for Progressive Communications and Privacy International, are attempting to do just that. There is no way around it: digital tools and spaces are an expansion of our societies. And as we are in a battle for civic space in the real world, we also need to fight for our space online.