Communicating narratives about mass violence to a broad public is a messy and often complicated endeavor. Non-governmental organization (NGO) actors and other practitioners seek to impress on the world specific interpretations of these situations, yet they often face competing voices and varying receptivity across countries. What approaches are most effective, and whose narrative gets the most traction? My recent study, funded by the National Science Foundation, helps to shed light on these underlying and complex mechanisms of transmitting narratives to a broad public. Involving analyses of over 3,000 media reports and interviews with Africa correspondents and with experts in foreign ministries and NGOs from eight countries, this study addresses representations of the Darfur conflict across social fields and countries. The main findings indicate that although NGOs, governments and humanitarian organizations used different frames, the media prioritized narratives about human rights and criminal violence over those about civil war, humanitarian emergency and an aggressive state. Yet these portrayals differed among countries, often based on cultural factors. How does this filtering affect the global response to mass violence?

First, human rights NGOs framed the violence as criminal perpetration, consistent with and supportive of International Criminal Court (ICC) intervention. They provided high estimates of victimization and focused on purposeful actions by high-level leaders of the Sudanese state, seeking to advance justice and establish an understanding of mass violence as atrocity. Such framing works well in an era of what Kathryn Sikkink calls a “Justice Cascade”, and is also bolstered by Hyerjan Jo and Beth Simmons’ recent findings that ICC prosecutions substantially deterred violence by government and rebel actors alike. Importantly, human rights NGO campaigns supplemented ICC interventions that were strongly reflected in journalistic reporting.

.jpg)

Flickr/United Nations Photo (Some rights reserved)

How did differing narratives of violence in Darfur influence the world's response to a human rights crisis?

Yet, crime-focused narratives faced competitors. Diplomats, for example, used more cautious language. Preferring an armed conflict frame over a crime frame, they avoided pointing the finger at political leaders, stressed long-term and ecological conditions of violence, and provided low victimization estimates. Humanitarian aid actors equally avoided identifying Sudanese government officials as criminal perpetrators. While providing high victimization numbers, they focused on the suffering of internally displaced persons (IDPs) and in refugee camps, often downplaying victimization as a direct consequence of violence. These patterns may not be surprising, as interviewees confirmed that humanitarian aid organizations depend on government, and diplomats rely on Sudanese officials’ willingness to keep up negotiations.

Conflicting frames, and associated positions toward the ICC, at times resulted in open conflict between NGO sections. In one European capital, for example, a major human rights NGO invited a humanitarian aid NGO to a closed door meeting to express its dismay about the latter’s public criticism of the ICC. Several interviewees cautioned, however, not to interpret this as a zero-sum conflict. Medical documents issued by humanitarian aid organizations, such as certifications of rape, could later be used in criminal justice proceedings, and reports about patterns of injuries such as shooting wounds in the back or vertical to the axis of the body provided ample evidence for human rights campaigners. Simultaneously though, numerous aid NGOs were evicted from Sudan, especially when the ICC prosecutor cited their reports in the context of charging decisions. Médecins Sans Frontières is one prominent example, illustrating a dramatic flashpoint between bearing witness and providing aid.

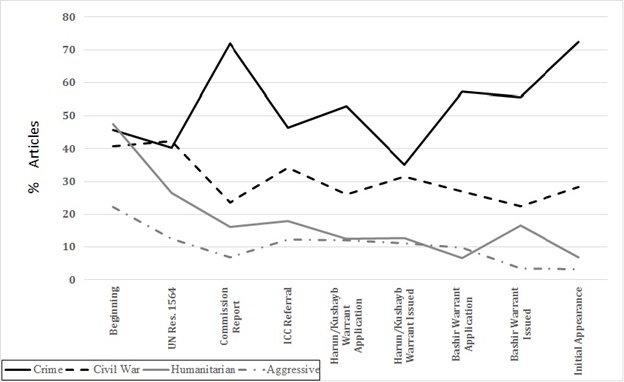

How then do these competing stories about the violence in Darfur reach audiences across the globe? Journalists used all three fields as sources of information, but their reporting privileged the human rights and criminal violence narratives over civil war, humanitarian emergency and aggressive state frames. They did so especially after the International Commission of Inquiry issued a report in 2005 and after the ICC’s indictment of President al Bashir (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Competing representations of the Darfur conflict in news media from eight Western countries

Notes: This figure is based on analysis of 3,387 news reports and opinion pieces from eight countries; for methodological details see the full study here.

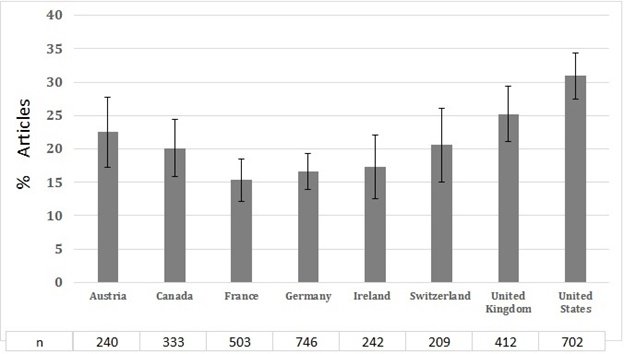

Despite the overall privileging of the crime frame, media from the eight countries differed in their preference for the competing narratives. For example, the use of the term “genocide” in media reports varied substantially (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Use of the term “genocide” in media reports on Darfur across countries

Note: Figure includes confidence intervals for each country sample.

American journalists, who generally preferred the crime frame, also used the genocide label more often than their colleagues from other countries. On the one hand, this may be surprising given their country’s reluctance to ratify the Rome Statute on which the ICC is based. On the other hand, it is consistent with the broad-based mobilization and genocide rhetoric by the Save Darfur coalition, encompassing some 200 civil society organizations, liberal and conservative as well as religious and secular.

Ireland offers an interesting contrast. Their reluctance to using the crime frame and the genocide label is explained by the strong humanitarian climate in the country. The latter is manifested in a pronounced aid orientation of Irish foreign policy and close cooperation between the state and humanitarian aid NGOs, including those affiliated with the Irish Catholic Church. Collective memories of the Irish potato famine and extreme poverty provide cultural support. Multivariate statistical analyses show that a national focus on aid programs is generally associated with less use of the crime and genocide labels, lower victimization counts (with the exception of displacements), and a less frequent identification of the Sudanese state as a criminal organization. As a final example, German media reported extensively about Darfur and generously applied the crime frame. Yet, media reports and interviewees quite rarely used the term genocide, and respondents explained that they were cautious about likening mass atrocities such as those in Darfur with the Shoah.

NGO actors carefully adjusted their rhetoric and were mindful of sensitivities of potential activists (e.g., anti-militarism in Germany and Austria); pillars of civil society organization (strong role of churches in German humanitarian aid); an intense anti-genocide rhetoric in civil society mobilization (US); aid-oriented foreign policy (Ireland); and status as former colonial powers in Sudan (UK) and in neighboring Chad (France), associated with substantial expat communities in these countries. Interestingly, such caution was almost always reflected in media reporting in their respective countries.

Despite varying preferences for competing frames, in the case of Darfur the crime frame prevailed. While the indictments of Sudanese officials have not resulted in arrests, they have generated an image of the violence specifically as criminal violence. The actions of supposedly responsible political actors have been delegitimized; and, as one of my interviewees—a journalist—observed, rebels and militias, who used to show off their child soldiers and direct him and his colleagues to piles of corpses they had left behind, have become much more cautious in doing so after new criminal justice interventions.