When communities bring legal complaints in an effort to hold companies accountable for violations of the right to water, they often face an evidentiary challenge: how do you prove that mining caused the contamination? While companies may monitor the water during the operation of a mine, they are not usually required to publicly release data concerning the environmental conditions before mining starts. The absence of rigorous baseline data makes it difficult for communities to defend their rights.

Communities living within a permitted mining area in the north of Haiti will, we hope, be able to prevent environmental damage or hold companies to account for future environmental harms, should they occur. Between 2016 and 2018, residents in the commune of Quartier Morin in the north of Haiti and the Kolektif Jistis Min (Justice Mining Collective, KJM), a network of social movement and community organizations, worked with American scientists and human rights attorneys to establish a baseline water study for their area, which falls within the purview of a permit that authorizes a company to build a gold mine.

The study included a map of water source locations in the area, water quality measurements for more than 75 water sources, and laboratory test results from 48 sites to determine the concentrations of chemical properties. The interdisciplinary team also documented changes in water level in three household wells over a period of two years. These communities now own what may be the first baseline water study conducted with and for a community before a mining company builds a mine.

The team concluded that industrial gold mining poses serious risks of contamination and diminished water in northern Haiti. The scientists confirmed that the aquifer in the area was healthy and needs to be protected. The study found that the majority of boreholes pumped water that did not contain harmful contaminants, indicating it was safe for drinking or other uses.

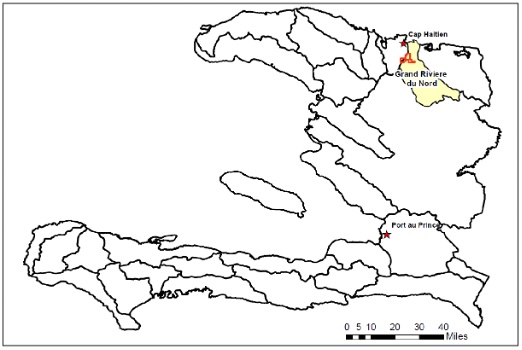

Figure 1. Location of the study area (red outline) south of Cap-Haitien, Haiti and within the Grand Riviere du Nord watershed (yellow shaded region).

However, all of the hand-dug wells, which access the shallow groundwater, tested positive for e.coli, indicating fecal contamination. If a mining company extracted large amounts of water, shallow and deep groundwater resources would likely be depleted and more susceptible to contamination. If, as a result of company groundwater extraction, wells ran dry and pumps were infiltrated with e.coli or metals from the mining process, this would entirely deprive the community of potable water. This would amount to a plain and egregious violation of the community’s right to water.

The data, owned by community members, are an asset in the struggle for community self-determination and corporate accountability.

Community Resistance to Mining

Over the past ten years, communities in Haiti have steadily built resistance to industrial gold mining, with activists and community members concluding that metal mining is not an appropriate economic activity in Haiti. The country is one of the most densely populated in the world and arguably one of the most environmentally degraded in the hemisphere. Communities have also pointed out that the risks of mining—to water, to the environment, and to peoples’ way of life—outweigh the uncertain benefits. They also do not trust the under-resourced government to promulgate and enforce strong environmental protections against powerful mining companies. These concerns have grown more intense as conditions in the country have deteriorated a bit more each day due to the political crisis, destruction of the republic’s institutions, and the absence of a government capable of managing the country. Thus, developing the mining industry in this context would be detrimental because the Haitian State would not be able to regulate the companies’ actions.

In the wake of the 2010 earthquake, the government of Haiti identified mining as key to making Haiti an “emerging economy.” Kolektif Jistis Min (KJM) formed in 2012 to inform national dialogue about the risks and benefits of mining and to build a national network of communities under mining permit. KJM recruited the Global Justice Clinic (GJC) at NYU School of Law to help gather quality information about the corporate actors operating in Haiti and support communities affected by mining such that they know and can defend their rights.

In the first four years of organizing, KJM hosted activists and advocates from the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Peru, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, seeking advice from those who had spent decades fighting for community survival in the presence of mining. The most consistent messages were: (1) social opposition is most successful before a company builds a mine; and (2) water is more valuable than gold. KJM, with input from member organizations in communities throughout Haiti, built their first campaign on the right to water.

KJM and GJC co-created a community water monitoring program and hosted an American hydrogeologist to teach residents to take simple water quality measurements to build baseline data in areas under a mining permit. Many communities collected and banked data, but one area was particularly organized: the communities around Morne Bossa, the site of one of three exploitation permits in Haiti, which authorizes a company to build a mine. Residents believed that they were blessed with comparatively good access to safe drinking water; they wanted to protect the resource and sought further information about the quality and quantity of the water in their area. This community was especially aware of the crucial role of water in its economy: agriculture is paramount, followed by Kleren, an artisanal spirit made in a water-intensive process from sugar cane.

Community Research as Science

KJM and local residents expanded the water monitoring program by conducting a census of all the households and all public water sources—hand pump wells, hand-dug wells, springs, rivers, and streams—in the area. GJC taught KJM and local residents to use the Kobo Toolbox app on smartphones to gather GPS points for 1,134 households and more than 200 water points. Kobo then auto-generated community maps that visualized the data. GJC and KJM then further built upon the water monitoring program to include a collaboration with U.S.-based scientists. The household census and the water point census informed the scientists’ sampling plan, providing a sense of relative population density and the spatial distribution of water points. The census also noted water points of particular importance to local communities and helped the scientists determine at which sites to conduct the full suite of measurements and lab tests.

The scientists continued to rely on local knowledge as they were led by community members to water points to conduct measurements and collect samples. Community members explained to the scientists how the water was often used, including for economic activities in a given area—cattle raising, farming, or kleeren distillation—that could influence water quality. In addition, the scientists showed residents how to take water measurements, which they continued to collect after the scientists returned home.

The scientists arrived in the area to exchange and collectively build knowledge, not to deliver it. Residents learned that what they know, through daily life, observation, and practice, has value. Local knowledge made the hydrological baseline study more valid and more useful to the communities that participated in the process.

The water study alone is a significant contribution to communities’ effort to resist gold mining. But of equal importance, the process of conducting the study also fueled local organizing. The participation of women was essential, as women in the community had the most intimate knowledge of the use of, and impacts to, local water resources.

In May of 2018, when the water study was nearing completion, thirteen community organizations signed and publicly released an open letter to local and national government authorities. The letter, Wi ak Lavi, Non ak Eksplwatasyon Min (Yes to Life, No to Mining), rejects mining and calls for agricultural reform, education, reforestation, and potable water. The thirteen community organizations represented a broad cross-section of local society, and the letter is one of the strongest statements of social opposition to mining in Haiti to date.

Conclusion

Communities in Morne Pele, Haiti now own data that demonstrates that the water is not contaminated with metals and chemicals that often accompany mining. Maxène Joseph, a community leader who participated in every phase of the water study, stated: “We have data that shows how our water is today, and we see that we must protect—and improve—what we have. We call on local and national authorities, as well as mining companies, to suspend mining activities definitively, in our area and in Haiti.” Maxène, Kolektif Jistis Min, and communities throughout Haiti are inspired by the recent decisions in El Salvador and Honduras to ban metal mining altogether. This study is one step towards building the power of Haitian communities to make their own decisions about mining, too.