There is a famous allegory proposed by Plato known as the "Myth of the Cave." Through it we could imagine a dark cave in which prisoners have lived since their early years. Although they are unaware of their limitations, they live tied up and unable to see external light, but rather only shadows projected on the cave walls. These distortions of shapes and movements are the only way through which these prisoners can understand the vastness of the outside world, and because of this, have a very limited and skewed understanding of reality.

The allegory is useful for thinking about situations where there are imposed limitations that prevent us from understanding the world in a broader, truer, more enlightened way.

I propose a parallel with the way we are taught to fit into boxes in many areas of our lives, especially in academic and intellectual spaces. One of the consequences of dividing knowledge between the humanities and exact and biological sciences is that we are more likely to adopt a series of stereotypes and limiting beliefs about either field. A good example of this is reflected in the joke that "to be from the humanities is to trust that the change is correct," alluding to a supposed difficulty in making quick calculations by those who are "from the humanities."

Law courses and forensic practice reproduce much of this philosophy, as if our entire lives could be reduced to graphs, spreadsheets, and scientific studies. Brazilian courts, in turn, rarely incorporate quantitative or scientific evidence and analysis into decision making.

The last few years, marked and greatly worsened by the pandemic, have made clear to us the importance of science and how reality can impose itself on our lives like an uncomfortable flash before our half-open eyes. In this period we have been exposed daily to graphs, projections, curves, maps, indices and rates, and a technical-scientific vocabulary that we did not previously have.

After an adaptation period in which our "mental pupils" have adjusted to the new information, one possible observation is that being able to demonstrate our ideas beyond words is fascinating. It also greatly bolsters our efforts of argumentation and didactics, radiating our message far beyond the reach of verbal or written descriptions, at the speed of light at which social networks operate. I’d like to expand on this idea with several cases.

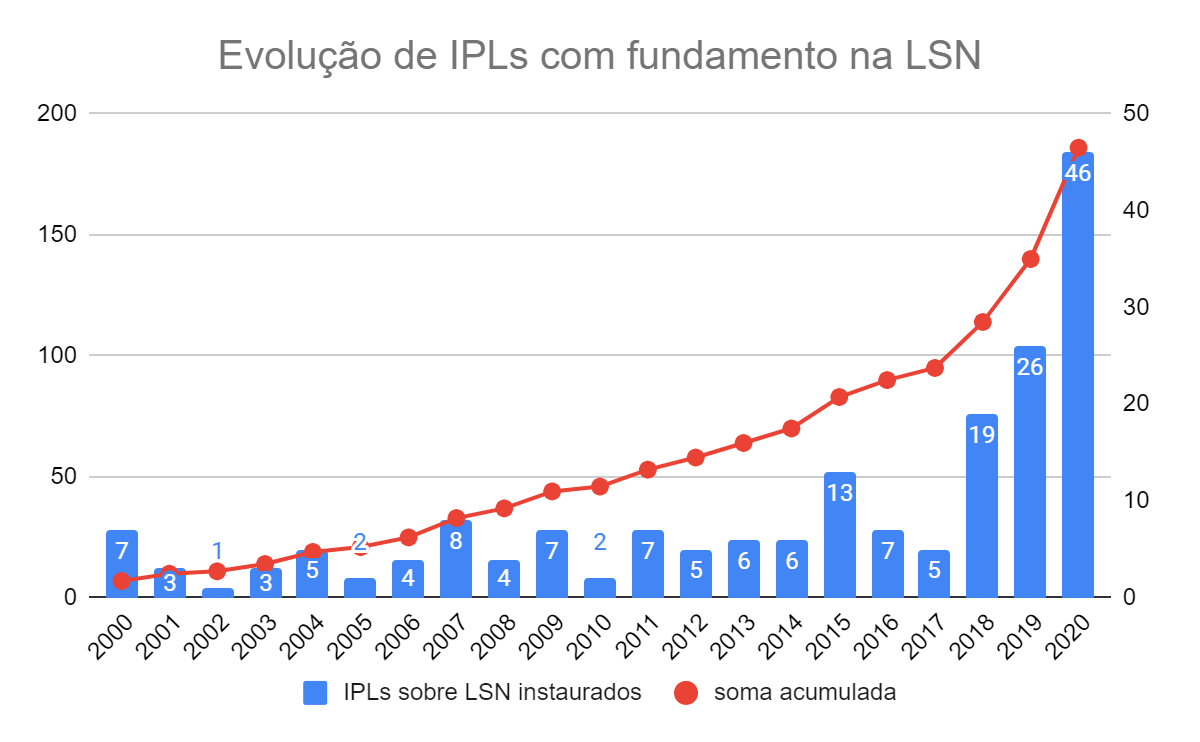

In Brazil, we know that Jair Bolsonaro's authoritarianism flirts with the use of abusive instruments that we have inherited from the military dictatorship period, such as the "National Security Law" (LSN). But to effectively demonstrate how widespread and rampant this use has become, it is not enough to merely state this.

As much as telling the stories of journalists and personalities who have come under undue investigation has proven to be an important whistleblowing tool, coming to a similar conclusion could depend on subjective factors of the other party, such as ones’ sympathy or dislike for these figures.

So, rather than simply spending gallons of ink to convince the public that Bolsonaro had been misusing the National Security Act, data collection and graphic storytelling allows us to be much more convincing and didactic, showing this abuse in a comprehensive manner:

Source: Federal Police. Access to Information Request No. 08198.008721/2021-42

The supposed neutrality of the numbers (which we can discuss further) helps convince us that there is a problem, in that it is hard not to recognize that nearly a fourth of all investigations into journalists have been concentrated in the last few years.

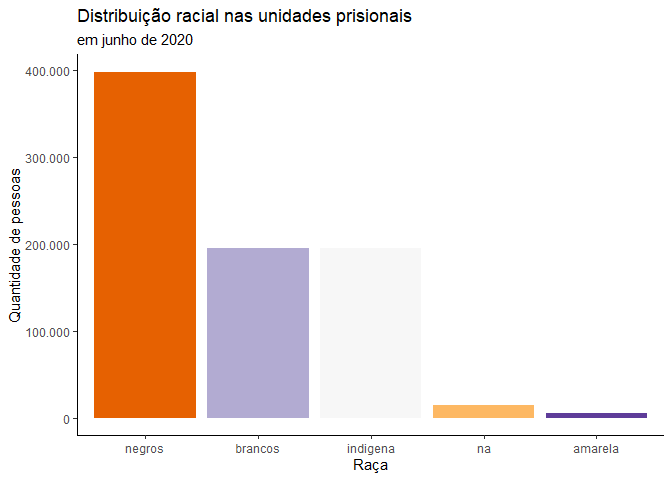

Data and visualizations can also be an ally when uncovering the perverse effects of racism. We know that the reality of the Brazilian prison system is notoriously unknown to most of society and thus, it is especially important to convey this understanding by providing a more forceful dimension of racial bias.

Source: Data from the National Penitentiary Department System (SISDEPEN). Own treatment and elaboration: https://github.com/rfdornelles/penitenciaR

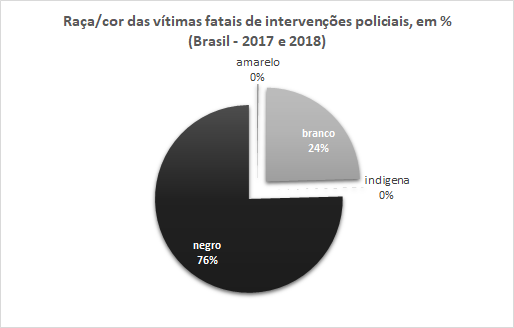

For some, to hear about "genocide of the Black population" may seem like a mere rhetorical resource or just an inconsequential bias “human rights people." However, gathering data and exposing them to our interlocutor can be effective in disturbing and illustrating the seriousness of the problem in Brazil, where Black people killed are killed by the police three times more than white people:

Source: Brazilian Public Security Forum. https://www.forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Anuario-2019-FINAL_21.10.19.pdf

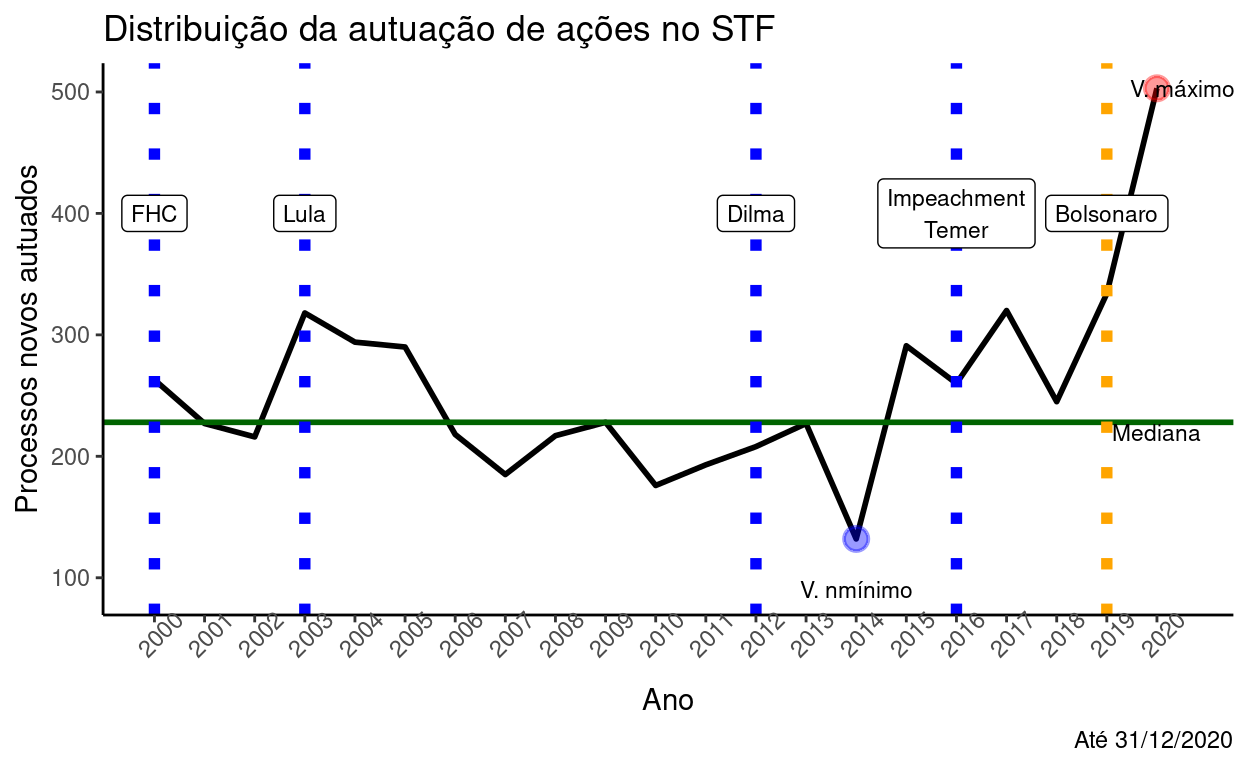

But it is not only "those outside the bubble" who can benefit from better using systematized data and information. This data-centered approach could be fundamental in better understanding our institutions and designing more effective strategies.

In the field of strategic litigation, we can apply statistical techniques to observe how institutions behave, taking a more accurate - and less gloomy - look at these phenomena.

Rather than relying on our intuition (which can be manipulated by the sounding boards of social media algorithms), wouldn't it make sense to look at data and try to understand the role of the Supreme Court (STF) in the current moment we are in?

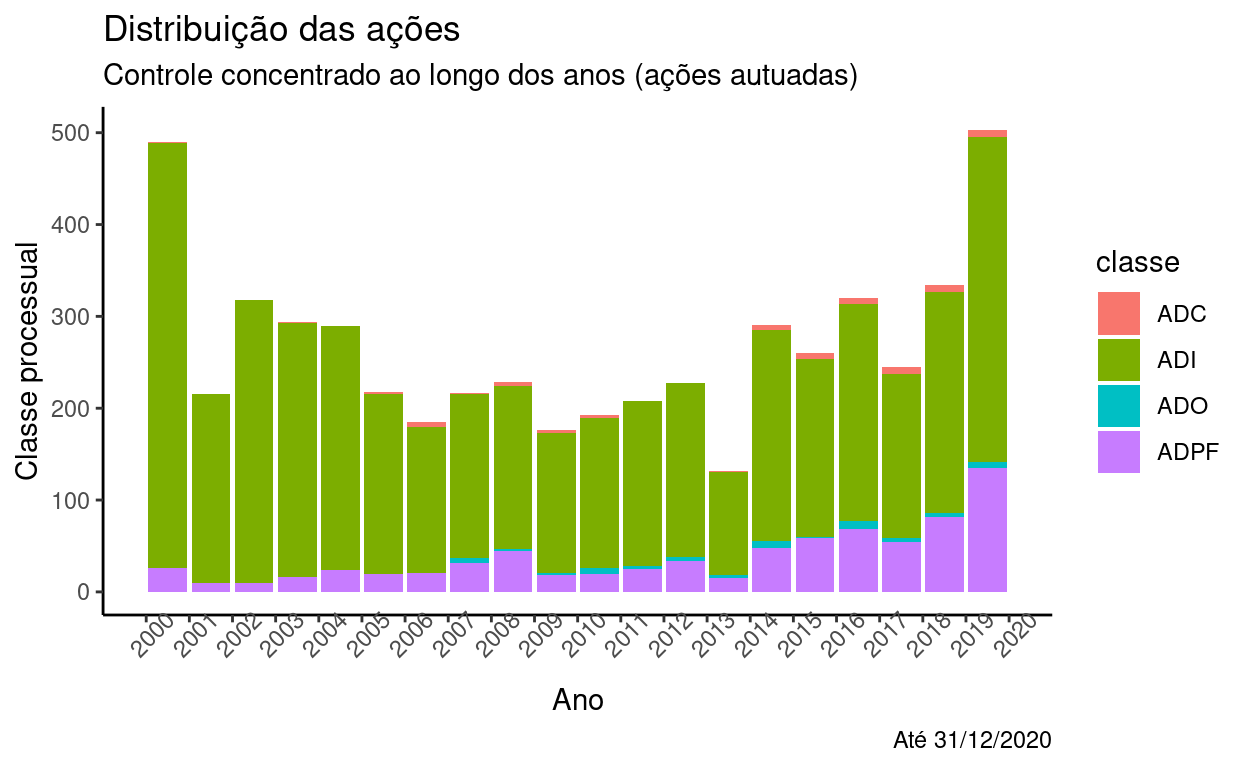

Own extraction from the Supreme Court website. https://lab.abj.org.br/posts/2021-04-13-stf-controle-concentrado/

The graph above screams that there is an increase in the amount of actions taken to the STF since 2018, indicating the importance of this Court in the current moment. This data can also lead us to think about the impacts of this intensified litigiousness on our strategies. Let's look at another aspect:

Own extraction, from the Supreme Court website. https://lab.abj.org.br/posts/2021-04-13-stf-controle-concentrado/

We can observe, among other aspects, an increasing use of "ADPF" (Argument of Non-Compliance with a Fundamental Precept) -type of actions which may be used as a reaction to other types of norms not traditionally questionable through Direct Unconstitutionality Action (ADI), as a creative reaction to the also creative Bolsonarist authoritarianism.

I don't want to overstate how tired we already are of witnessing injustices. I would, however, like to bet that these brief provocations can bring out the brightness in our eyes - the so-called window of the soul - and allow us to improve our legal strategies, making our efforts with litigation more convincing and in general more assertive.

In a scenario of weakening democracy, attacks on institutions, and a likely generalized worsening of social indicators, it seems appropriate to build bridges with academia, research centers, and other areas of knowledge, using technology and knowledge to bring reality more effectively into the judicial records.

So perhaps we can make Plato proud by emerging from those caves we have chosen to entrench ourselves in, illuminating our "insights" with data to see and reach new, previously hidden paths.