Public support for human rights is not easy to achieve and maintain. After all, human rights exist to protect individuals not only from the tyranny of states, but equally from the popular prejudices and discriminatory attitudes that threaten the rights of marginalized and unpopular social groups. Sometimes human rights exist to protect individuals who we might consider to be legitimately unpopular, such as those involved in terrorism.

Yet action to build public support—or at very least public respect—for human rights is critical. As Rachel Krys and Kevin Nix have both noted, the way we frame certain human rights can dramatically change public opinion of those rights. Effective defence of human rights is at least as much about battles in the court of public opinion as it is those in courts of law. Without it, the opponents of human rights are free to shape the public narrative about human rights. This neglect can have dire consequences, because public opinion is capable of nurturing or destroying laws and institutions.

The human rights brand is under attack globally. In Africa, leaders accused of war crimes and the popular press—which they often own—cast themselves as the ultimate victims of the International Criminal Court, itself portrayed as a Western imperialist venture. In Europe, governments including the UK and Russia accuse the European Court of Human Rights of overreaching and undermining national sovereignty, threatening to leave the regional human rights system. In Brazil, as in Britain and elsewhere, human rights are often thought to benefit criminals over the victims of crime.

In her recent piece for oGR, Wendy Wong argues that, “human rights are increasingly part of our moral discourse, and as such, are debated, used, and misused in all kinds of ways.” But what if the discourse is almost wholly negative? In various countries human rights are increasingly cast and regarded by significant numbers as undemocratic, as undermining security and as violating justice and fairness by placing irresponsible individuals above the interests of the wider community. Human rights are discussed, yes, but because the terms of that discussion place human rights in opposition to commonly held values, they are increasingly at risk of being rejected.

Yet such negative opinion is not inevitable. With commitment, resources and innovative new approaches, it is possible to turn these views around. For example, in the UK some are virulently opposed to human rights, some are supportive and some are ambivalent. But the majority are conflicted. This fourth group provides the opportunity to build public support for human rights because they remain persuadable—with the right messages, delivered by the rights spokespeople—that human rights are overwhelmingly a force for good.

Addressing public opinion is not, first and foremost, a matter of providing accurate information and myth-busting (though both have a role). A body of evidence from cognitive science has shown how people’s deeply embedded opinions about issues render them immune to information that fails to accord with those opinions. People seek out information to confirm their existing beliefs, not to challenge them. This is why myth-busting, as Nix also argues, often has an unintended effect whereby people remember the myth and not the correction.

Moreover, the strength of those opposing human rights lies less in the inaccurate information they promote, but in the successful way that they managed to frame discourse on human rights. This is communication rooted in and speaking to values, employing powerful and memorable metaphor and imagery.

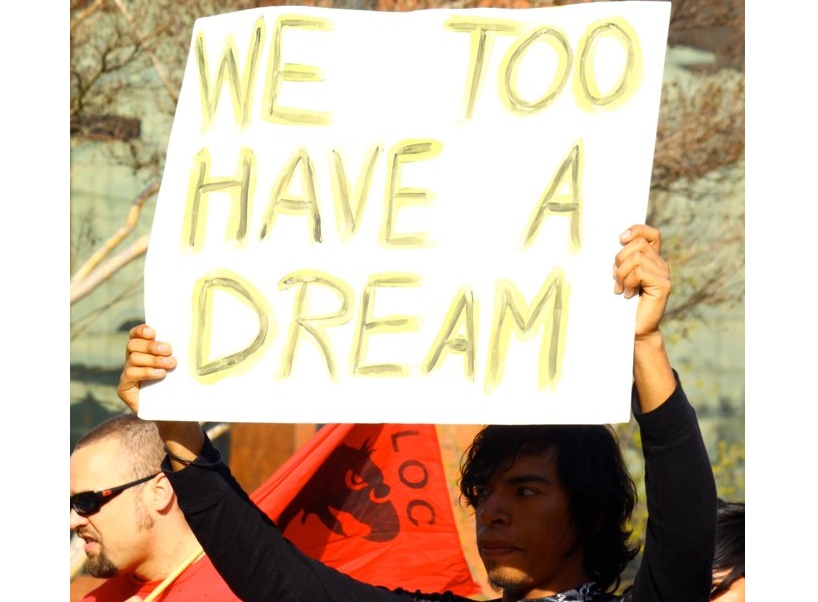

Flickr/Justin Valas (Some rights reserved)

"Migrant rights campaigners in the US have shifted their approach by developing frames and narratives designed to appeal to American values, such as “the dreamers”, rather than confronting people with accusations of racism."

In the UK this summer for example, Ministers have used terms such as “swarms” and “marauding” to describe the actions of migrants and asylum seekers trying to gain entry to the UK via the channel tunnel. The painting of such an existential threat is then deployed to orientate the public and political debate towards deterrent measures rather than concern for human rights.

It is to this framing, and counter-framing, of public discourse that successful influencing of public opinion on human rights must turn.

It is to this framing, and counter-framing, of public discourse—the employment of values and metaphors in communications and their effective deployment—that successful influencing of public opinion on human rights must turn. For example, migrant rights campaigners in the US have made a huge shift in their approach—and with positive results—by developing frames and narratives designed to appeal to American values, such as “the dreamers”, rather than confronting people with accusations of racism.

The Thomas Paine Initiative (TPI), of which I am Director, is a donors collaborative established in 2012 that is dedicated to building public support for human rights in the UK. Our starting point has been lessons drawn from other fields that have seen major leaps forward as a direct result of their learning to reframe the public discourse, such as the campaigns in the US and internationally for same sex marriage. Such campaigns place heavy emphasis on understanding public opinion and the kinds of values, metaphors and messengers that can mobilise rather than repel public support for progressive policies, programmes and behaviours.

We are at the very beginning of learning how to deploy these techniques in relation to human rights in the UK, with modest resources and a swamp of toxic public discourse to wade through. But following extensive research we now have an evidence base concerning the messages and spokespeople that can command public support, and we have begun to see these enter the public discourse.

Through the Equally Ours initiative, which TPI supports, we have managed to enlist organisations such as Age UK and Women’s Aid to develop and run high impact, high reach communications campaigns in recent months. These campaigns emphasise the importance of human rights to older people receiving care, and to women experiencing domestic violence. We have also helped human rights organisations to communicate differently, with the evidence on public opinion shaping the content of Amnesty UK’s recent campaign to save the Human Rights Act and the focus and content of RightsInfo , a project supported by TPI that employs infographics and a light editorial style to engage and inform on human rights.

A paradox of upholding universal human rights is that it demands we focus communications efforts on the particular. This is not a new insight. As Eleanor Roosevelt said on the tenth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1958:

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home…. [in] the world of the individual person…. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.”