In 2011, I spent six months working in Rwanda with a local NGO. Through my work, I witnessed traumatic events that affected me deeply and for which I was not adequately prepared. For months after I returned to the United States, I would see amputations that weren’t there and break down in tears over insignificant things and at inappropriate times. I had never cried in Rwanda, and I was surprised by how emotional I was. Because I was new to field and unprepared for the mental health impacts of working with such difficult issues, I didn’t realize that I was just processing the emotional trauma of my work in Kigali. Today, the mental health impacts of my current work are less intense, usually manifesting in waves of fatigue or the inability to focus. Now, as then, I sometimes get frustrated with myself, wondering what is wrong with me or why I am struggling.

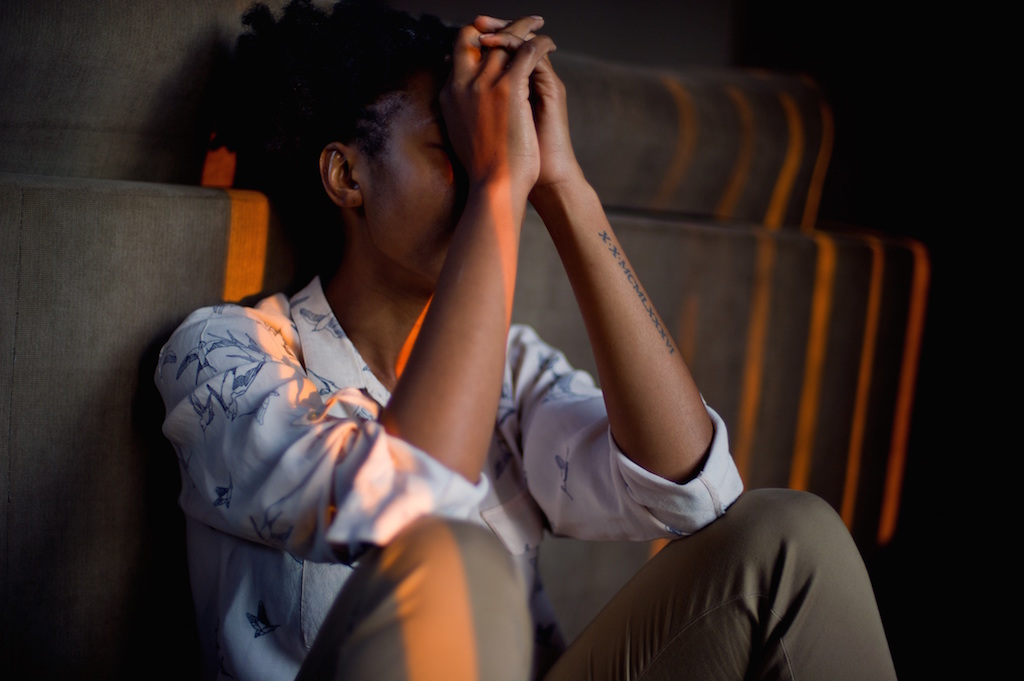

Mental health challenges are common among human rights workers.

I often feel alone in these moments. I feel as though I am suffering individually, and that my struggles and weaknesses are unique. I have to proactively remind myself that this perception is, in fact, false. Mental health challenges are common among human rights workers. We face high levels of both acute and chronic stress. We also tend to exhibit character traits such as perfectionism, which make it difficult to recognize and admit that we have a problem, and we are often too worried about stigma to get help. That worry unfortunately seems to be well-placed, as there are often cultural and professional repercussions for speaking up. For example, rights workers know that if they admit that they are struggling, the organization may simply pull them out of the field. There is such stigma around mental health that we can feel isolated and weak for experiencing mental health challenges, and it can be hard to get help.

Pixabay (Some rights reserved)

"I didn’t realize that I was just processing the emotional trauma of my work in Kigali. Today, the mental health impacts of my current work are less intense, usually manifesting in waves of fatigue or the inability to focus."

Exacerbating this issue is the fact that human rights, as a field, generally employs the notion that we are instruments, not people, making it easy for human rights advocates to feel guilty for being human. It also means that we are often left to cope on our own, with little organizational support. However, not addressing our own humanity and needs distances us from those we are working with and limits our professional capacity by increasing our vulnerability.

It took me a long time to think about my mental health and well-being not in terms of weakness or selfishness, but as part of my job that I must engage with to do this work sustainably. While I am not always successful in this re-framing, a number of realizations have helped me shift my perspective.

Once I admitted to myself that I wasn’t “fine” after I returned from Rwanda, I started doing research to understand what was happening to me. It was important for me to know and articulate what I was going through. If we know a thing and give it a name, it is easier to address. Trauma makes us feel out of control, and regaining this control is often a significant part of how we work through trauma. I can now more easily recognize when I am having an emotional reaction to the work I do. Once I can name what I am experiencing and thereby re-establish control, I can help myself move past it.

I also try to remember that I am not the only one facing these challenges. The emotional impacts of our work are usually quite visible among human rights advocates, even if this field has yet to have a comprehensive dialogue about it. Recent research has started to inform what many of us anecdotally know: human rights advocates experience high levels of trauma and burnout. Knowing that others also have a hard time dealing with the emotional implications of this work makes me feel less like my feelings are something to be ashamed of, and has given me permission to face those issues honestly.

Perhaps the most important factor in shifting my perspective is recognizing that—for better or worse—if I don’t address my mental health and holistic well-being, sooner or later, I will be unable to continue this work at all. As the late Tooker Gomberg said, I will “become no good to anyone, especially [myself].” Moreover, it is critical for me to understand and address these issues not just for myself, but also for those I work with. If my speaking out about these challenges and the way I cope can help others in their own struggle, then it is all the more important that I do so.

However, the pressure for change cannot solely be the responsibility of individual advocates like me. Human rights organizations have an important role to play in shifting the discourse about mental health and well-being from one of weakness and shortcoming to one of capacity-building and strength. We need strong leadership to start the conversation on how to address these challenges. Organizations must do their part to provide information and resources, and to see advocates as people, not just workers. This is critical given the stigmatizing nature of these issues and the difficult contexts in which we work. We can borrow from other similar fields, such as field journalists, combat veterans, and even emergency-room doctors that have already begun to recognize and address these issues with initiatives such as treatment programs, fundraisers and awareness events. However, we also need to develop tools and resources geared specifically to human rights work. It is not an easy task, but we must start by having the conversation.

I’m still afraid of many things. I am afraid of acknowledging my own limitations and needs. I am afraid that future employers might punish me for admitting that I have them. However, we know that many human rights workers will encounter these challenges at some point during their career, so we have to face this, regardless of whether we want to or not. I hope to be part of a new generation of human rights workers who will reshape our institutions and expectations so that we can be healthier people and be better at the work we do.