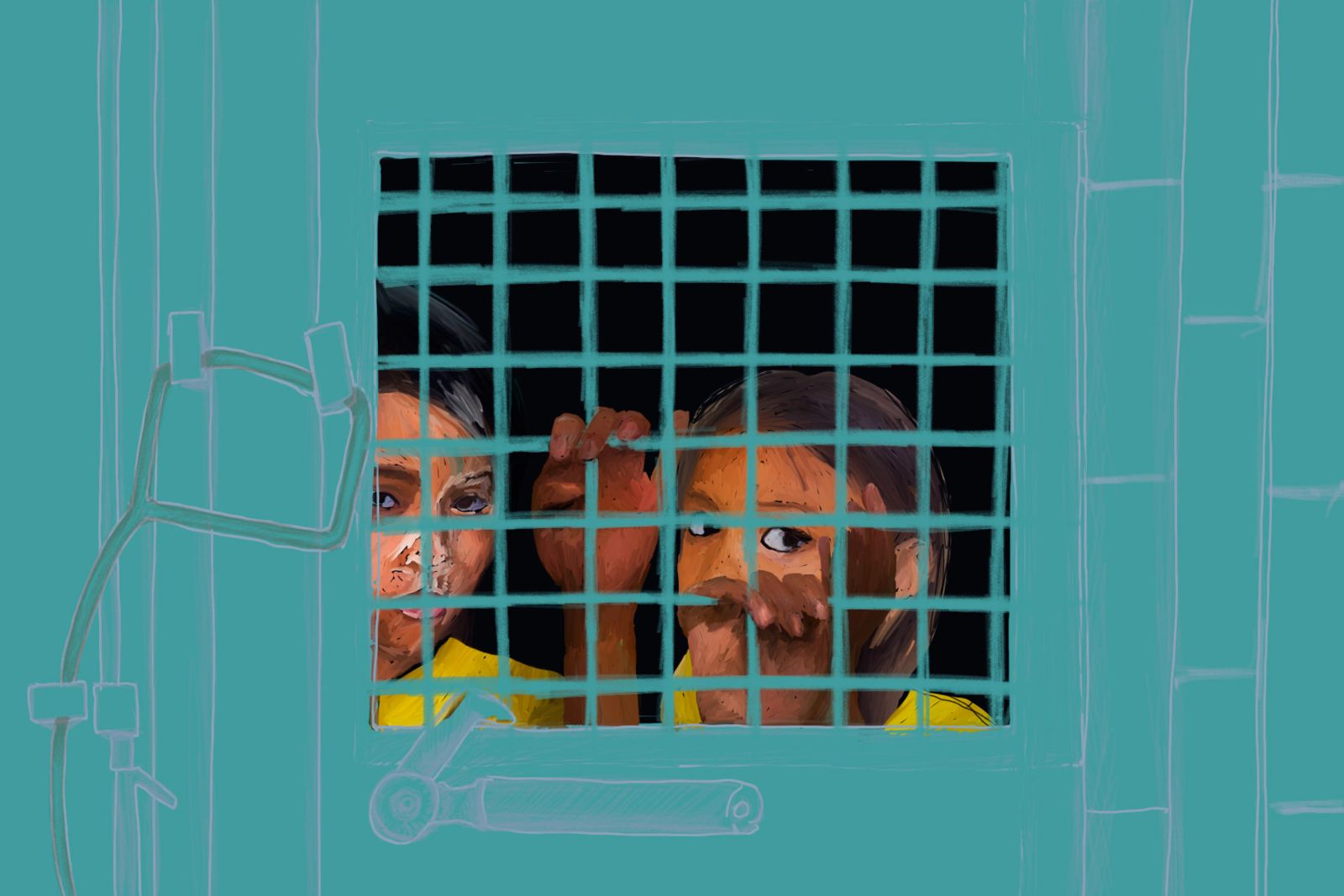

Jenny was 17 years old when she was arrested in December 2020 for a drug-related offense in the Philippines. A mother to a five-year old child, Jenny endured five months in an adult detention facility before she was finally turned-over to a juvenile detention facility.

Like Jenny, Anna was still a breastfeeding teenage mother when she too was turned over to the same facility in 2019 for resistance and disobedience. She was forced to leave her infant behind.

The stories of Jenny and Anna are common but largely invisible, as human rights organizations and media in the Philippines and internationally have focused their attention on the death toll of Duterte’s war on drugs. As most directly affected victims are men or male youth (often below the age of 18), there has been a clear gender bias.

However, the war on drugs cannot be reduced only to the killings of men and male youth. It affected families and communities in devastating ways and transformed the relationship between the state and residents in poor, urban neighborhoods. It led to a dramatic rise in incarceration and massive overcrowding. Juvenile detention has also risen sharply.

We met Jenny and Anna as part of an intervention and documentation project following children from families and poor, urban communities via police officers, social services, and child protection agencies to the juvenile detention centers. Initially, we had not taken full cognizance of the gendered nature of juvenile detention. We worked through categories of children at risk and children in conflict with the law (CAR and CICL, respectively) as main end beneficiaries, which appear ungendered.

However, as Anna and Jenny’s stories illustrate, the consequences of detention are very gendered. Our documentation around the interventions illustrated the gravity of the detention and the amount of trauma produced by the isolation from families and often rough and violent treatment by law enforcement agencies prior to the detention. As our research illustrates, children are often victims of violent forms of discipline at the hands of local law enforcement. Children went hungry, not least because their parents and families could not visit them to bring food during the harsh lockdowns.

Girls carried additional burdens. These experiences are characterized by intense loneliness and isolation because they were excluded from segregated activities. They are often even more stigmatized by their families and guardians because they have acted in ways or been associated with acts that contravene all notions of what girls should do. The fact that some of them are also mothers only increases their problems.

In this way, stereotypical notions of male criminality, female roles, and practical issues of place and resources all come together to render female detention particularly straining. We do not wish to belittle the problems facing boys in the juvenile detention centers. The notions that they are more prone to crime and violence put them at particular risk as we argue elsewhere. Rather, our point is that we need to take into account issues around gender.

While gender has become increasingly important in legal frameworks and development, there is almost a total lacuna on legal protection for women in detention, let alone girls. Only very general prescriptions exist, like the Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act or the Magna Carta of Women.

Broad guidelines like these fail to address the specific needs of girls in detention because the facilities have inadequate resources and programs which the management usually prioritize for the needs of the larger population of boys. As female CICL make up a small percentage of the population in detention facilities, programs and activities are usually availed by the boys. Furthermore, because of the lack of uniform guidelines on the management and treatment of female CICL in detention centers, activities and services vary from one facility to the other.

This means, as we also found in the detention center in which we worked, that the treatment of and services provided to girls, including teenage mothers, rests on the discretion of staff and the availability of resources. We met much empathy among staff and an appreciation of the predicament of girls. Despite budgetary constraints, there existed targeted activities which focused on their physical, mental, psychological, and spiritual needs. However, for the specific needs of young parents, especially teenage mothers, support and intervention were often inadequate and their experiences as young parents overlooked.

When Anna was still inside the detention center, she stopped breastfeeding her child. Due to the unintentional weaning, she experienced pain and discomfort. During the period when she was undergoing physical and emotional changes because of the childbirth, she received little assistance from the staff. Jenny, for her part, silently carried her experience of being slapped, cursed at, and threatened at gunpoint by the authorities in front of her child. Still reeling from the ordeal, her longing to protect and be with her child was met with a strict enforcement of a no visitor policy at the detention center because of the health and safety protocol lockdown imposed by the management. Her bonding with her child during her stay in the facility was limited to virtual visits—connected by technology but lacking the intimacy.

While there are provisions and a frequent willingness to protect girls in detention, there are substantial gaps in how the legal provisions are being implemented. Through our work in the communities and detention centers, we have been able to identify some avenues to address the invisibility of girls, especially teenage mothers, in the detention system. First, there is a need to simply recognize that female CICL exist and require specific attention. While they are fewer in numbers and the violence against them less spectacular than the boys, they have needs and rights that are different and equally important. Second, we need to mainstream gender concerns in the juvenile detention system in the Philippines and beyond.

Our experiences suggest that there is a willingness to engage with policy and guideline development but also a lack of skills and knowledge as to how to proceed. This is a key task for human rights organizations everywhere. Finally, and related, there is scope for developing a gender-sensitive protection policy for juvenile detention centers in the Philippines and globally.