Refugee activist Thuzar Maung was kidnapped from her home in Malaysia for supporting the Myanmar pro-democracy movement. In the Philippines, Marilou Verano faced libel suits for speaking up against the adverse impacts of mining in her town. In Vietnam, Dang Dinh Bach was arrested for his environmental activism. These stories are just a few examples of the risks that grassroots justice defenders face in the context of rising authoritarianism and the closing of civic spaces in Southeast Asia.

Since 2018, members of the Grassroots Justice Network have been collaborating to tackle this challenge. In addition to standing in solidarity with one another and lending support to access to justice campaigns, they have also been learning from each other about how they can continue to advance justice in the context of shrinking civic spaces.

In August 2024, community paralegals from seven countries across the region gathered at the Southeast Asia Regional Paralegal Exchange. These paralegals work across a range of issues, such as land and environmental protection, refugee and citizenship rights, and gender equality. Despite their different fields, they have a common understanding of their role, which is to empower communities by building their knowledge of the law and their rights, demonstrating how to leverage that power to drive systemic changes.

Below are some of my takeaways from this learning exchange.

Overcoming repression by empowering communities

Paralegals face some shared challenges in their work, particularly in contexts where civic space is shrinking and repression is a day-to-day reality.

The first is state repression, which manifests in different forms, including increased surveillance and security checks. A number of countries in the region have enacted restrictive digital regulations to suppress social media engagements, making it more difficult for paralegals to connect with others or organize communities. Following the coup in Myanmar, public trust in the legal system and law enforcement agencies has significantly eroded, making it more challenging to engage public institutions.

The second set of challenges includes threats, violence, harassment, and intimidation by both state and non-state actors. This includes physical violence, psychological abuse, and red-tagging (publicly labeling individuals as terrorists or communists). The third challenge is criminalization, which includes detentions, arrests, and trumped-up charges. Cases such as those of Thuzar Maung, Marilou Verano, and Dang Dinh Bach are unfortunately frequent, making it difficult for paralegals to carry out their work.

Despite the challenging contexts, paralegals use a number of strategies to effectively respond to their environments. One is forming or joining networks and coalitions that can provide essential support, enabling them to share resources, strategies, and experiences. Indeed, learning from each other is one of the most powerful ways in which they build solidarity. Reflecting on the learning exchange, a participant from Myanmar said, “Even though our advocacy efforts are currently restricted by political challenges, the exchange provided new strategies and perspectives. These insights will be crucial as we continue to work on enhancing our paralegal support services and advocating for justice in our communities.”

Paralegals contact national human rights agencies to raise issues, amplifying their voices and bringing attention to systemic problems. In Malaysia, they encourage closer collaboration with the local justice system, which enables paralegals to navigate the legal landscape more effectively and ensure that vulnerable populations receive the support they need. Others have organized emergency response teams and support groups for paralegals to provide immediate assistance during crises. In Cambodia, they equip themselves with skills in security analysis—both digital and physical—to improve their safety and effectiveness. Paralegals also undergo training on the use of secure digital platforms that can protect sensitive information and communication, which are crucial tools in high-risk environments.

Sustaining the work through challenging contexts

Community paralegals work not only in challenging political contexts but also on social justice issues where public opinion is sharply divided, such as the rights of LGBTQIA+ persons and refugees. And they do so with limited resources. At the August 2024 exchange, paralegals discussed the elements that are crucial for sustaining their vital work through long and complex change processes.

They see recognition as an important part of sustaining the movement. Levels of state recognition for paralegals vary across the region. Indonesia provides formal recognition, while Myanmar and the Philippines offer informal recognition. Other countries lack any form of official acknowledgment. There are varying perspectives on the value of recognition because it can also end up restricting their role by regulating who can become a paralegal and what they can do. Ultimately, recognition—whether formal or informal—must provide paralegals with access to tools, protection, and institutional support by means of funding, capacity building, and technical assistance.

Paralegals often rely on donor funding and volunteer work, but they need more stable financial support. There is a lack of second-line leadership, making it vital for veteran paralegals to engage in succession planning and capacity-building for the next generation. Paralegals highlighted the urgency of providing psychosocial support through counseling and mental health services to help manage the stress associated with their work. Finally, justice issues are complex, and paralegals emphasized the need for training and support to ensure that they can be effective in the long term.

Vision for a just future

Participants at the exchange underlined their role in addressing not only specific justice issues that affect them and their communities but also systemic changes and societal change. A participant from Malaysia noted, “More people should consider becoming paralegals, not just because they are personally affected by an issue, but because they want to contribute to positive change in society. Breaking the stigma that paralegals only engage in advocacy when directly impacted is crucial. Instead, we should recognize the importance of collective action in addressing systemic issues.”

Their vision for systemic change is bold and inspiring. It is defined by equality, justice, and dignity for all.

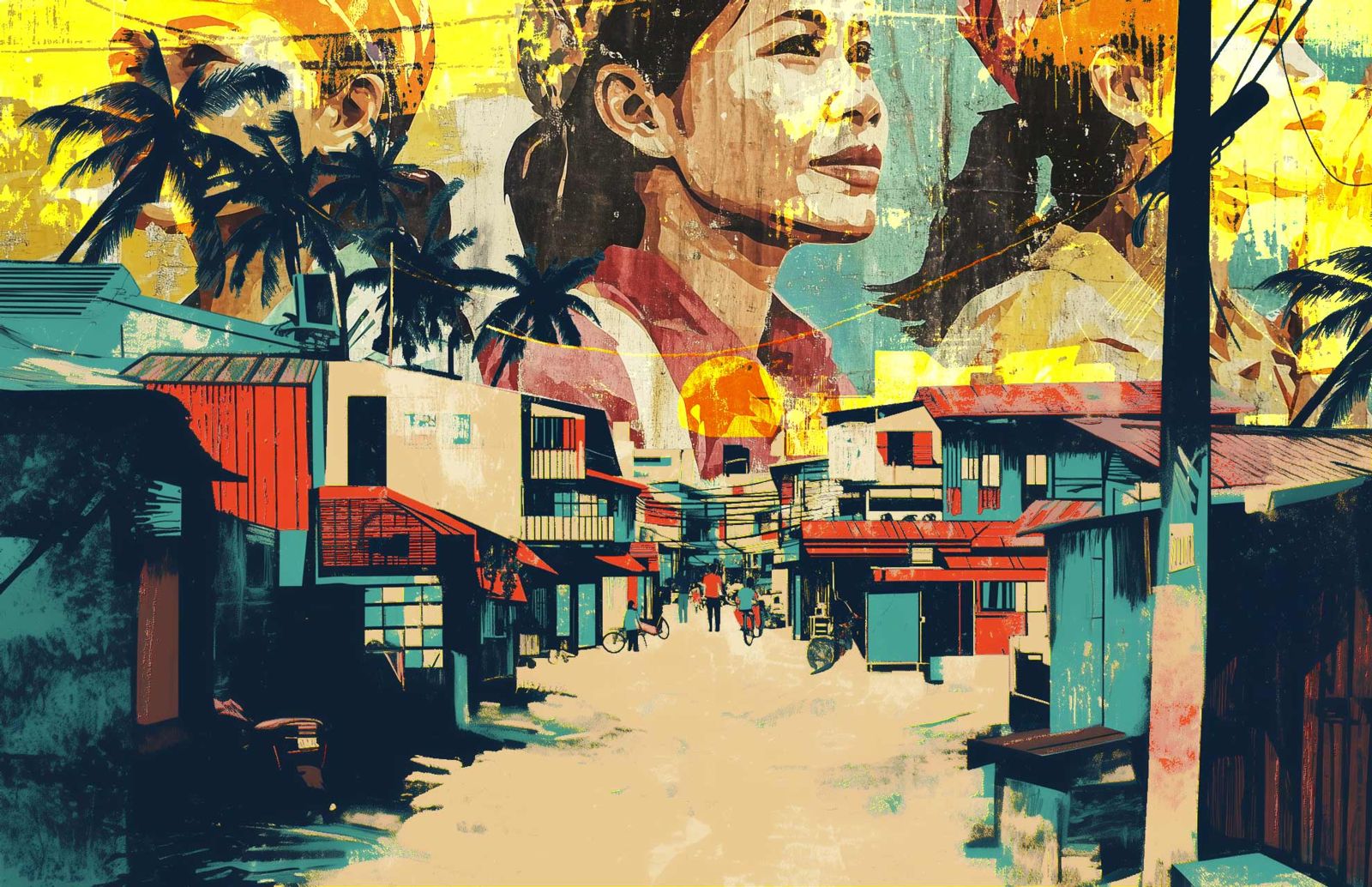

During a reflective drawing exercise, participants outlined their visions for the next five years. One participant from Laos shared, “I am drawing the scale that represents equality. I want everyone to have equal rights and have access to justice.” A participant from Malaysia disclosed their vision for a world where “Everyone is treated equally, with dignity, and with due process.” A paralegal from the Philippines revealed: “My drawing is a hand representing paralegals helping the community. The bird is the expression of freedom, and the torch is the champion gold medal for us paralegals.”

Community paralegals outline their vision for a just future.

The work of community paralegals is crucial to achieving greater access to justice for marginalized communities. There is an urgent need to support them with the necessary tools and skills, especially in environments that are repressive and threaten their security and voice. Creating collaborative spaces—where they can learn from each other and form bonds of solidarity—is essential to strengthening their capacity to hold the line under challenging circumstances. It is imperative that the rights community—as well as individual states—recognize community paralegals as essential agents of justice and advocates for their communities, ensuring their crucial role in fostering a more equitable society.

This blog is part of a series in partnership with Namati. See other blogs in this series here.