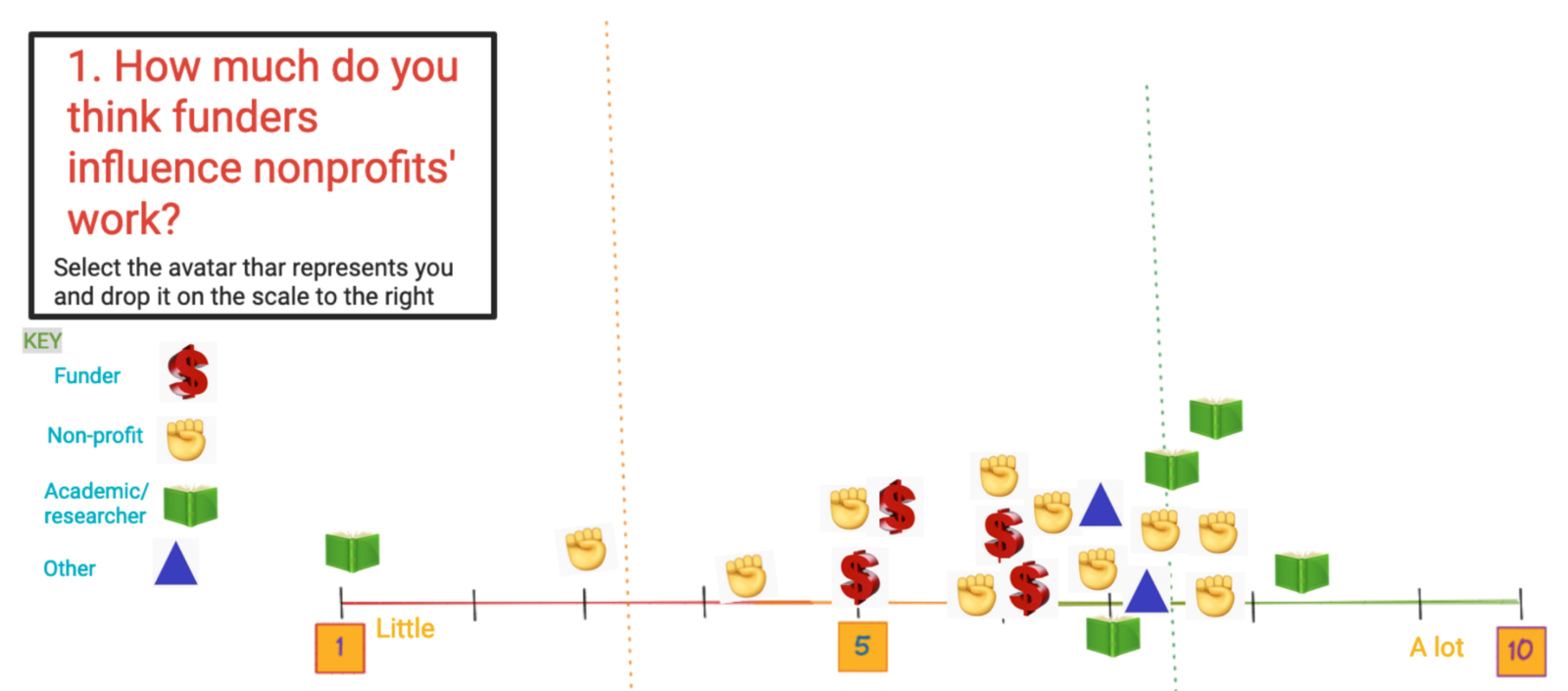

For nonprofits, securing funds and staying true to their mission often represents a difficult balancing act – one that can generate tensions within the organization and with partners and funders. During a workshop held at RightsCon, we asked participants—academics, activists, and funders—to state whether they thought funding had an influence over the work of nonprofits. Most participants believed this to be the case.

But what type of influence? As part of the workshop, we also asked participants to reflect on good and bad experiences they had seen or been exposed to, which we share here, together with their recommendations aimed at securing their autonomy and sustainable relationships with funders.

A breadth of experiences with funders

Most reflections from participants highlighted negative experiences with funders influencing non-profits’ autonomy—curtailing organizations’ ability to define their own objectives, manage their own budget, hire staff as they see fit, and even present their organization on their own terms.

For instance, one participant described the nonprofit they were working for as confined to the rigid parameters of the funder’s vision and goals for the project. Their actual needs were seen as outside of the scope of the funding, even when meeting those needs would have been beneficial to, and inclusive of, more communities.

Some commented on the problematic trend of using key performance indicators (KPIs) to quantify success for funders. Respondents emphasized that measuring impact is notoriously difficult, especially in social justice and civic tech work. Given that KPIs are often unable to capture the complexity of systemic problems, they often create mirages that consume energy and resources from staff.

Over time, insistence on the achievement of such metrics can undermine the trust of practitioners in the ability of their funders to actually understand the complexity of the problems they are grappling with and the types of timeframes they should be relying on when they design and execute their strategies.

While in practice funders may not have control over all of the negative experiences shared by grantees, participants expressed how their dependence upon funders often led leadership to go beyond what might have been actually required or expected by funders.

Fig 1. A screenshot of the consolidated outcome of three boards used during the workshop.

Despite the prevalence of negative experiences, participants also recalled some positive ones. Some participants felt that funders genuinely had the organization's best interests in mind. These respondents noted that they have felt respected and trusted by funders, some of whom have largely taken a “hands off” approach.

These relationships also fostered credibility for organizations, sometimes leading to additional opportunities and funding sources. Furthermore, one participant also noted that the restrictions imposed by funders (such as diversity and inclusion quotas) were used strategically within the organization to meaningfully change the organization’s internal structure.

Discussions regarding the challenges and limitations of nonprofit funding models should also keep these positive experiences in mind.

The way forward to secure autonomy

Based on our discussion, we believe nonprofits should keep these five things in mind moving forward.

First, diversify your sources of funding. An organization funded by lots of small contributions from multiple sources reduces the likelihood of being swayed significantly by any single funder.

Second, create consortiums of funders with distinct views and interests. Bring together funders with diverse interests and views that are in clear and public tension.

Third, form collectives with like-minded organizations. Sharing knowledge and sometimes resources can mitigate external influence by keeping organizations accountable to an issue's overarching needs, rather than the whims and desires of funders.

Fourth, develop clear and coherent red lines for funders. This includes discussions surrounding certain restrictions on who an organization can take money from.

And finally, rethink how success is measured and communicated. Performance indicators often do not embody the complexity of a problem, nor allow for the required fluidity to adequately address challenges. As such, participants suggested developing less restrictive performance metrics alongside an iterative and evolving definition of success within a project.

Funders should also take note of these five points.

First, demystify funding sources. Proactively clarify from the outset the specific requirements entangled with a certain type of funding, as well as the powers and liberties that funders may deploy throughout the funding period, such as the ability to cut funding or make project-altering decisions.

Second, encourage additional funders to enter the digital rights space. Strategies such as organizational collectives are most effective when organizations are able to hold each other to account and are not subject to the same funders or restrictions.

Third, develop a clear theory of change and explain how grantees fit into it. One way in which funders can be transparent about their influence is to be clear with each grantee and to society at large about how each of their grantee organizations fits into a larger project.

Fourth, keep windows open for reactive funding. General unresponsiveness of funders towards their applications has often challenged grantees’ ability to dynamically react to timely issues as well as keep their balance-sheet predictable.

And finally, award funds with a broad mandate. The freedom of broad mandates signals that funders trust the expertise of nonprofits to do what is most needed for any given project. This ideally would take the form of an endowment.

Protecting digital rights over the next few years will require that we strengthen existing institutions and spaces of policy coordination. One of the key challenges ahead is that the internet evolved as a globally networked technology. Big tech and other multinational companies, whose policies and technologies have become central to the way the internet works, are perfectly positioned to understand the internet at this scale. Governments, in contrast, developed institutions with a territorial understanding of power. Given their ability to span multiple countries, nonprofits have the ability to mirror the activities of multinational tech companies and help governments and other stakeholders shape the policies of these multinational companies in order to keep them accountable. Thus, digital rights nonprofits play a key role in keeping the internet glued together by shaping governmental and corporate policies in a way that enables it to continue operating across borders somewhat seamlessly.

However, the process of consolidation within internet markets and the heightening of geopolitical tensions suggest these spaces of global coordination and governance are likely going to be stress-tested. To make the multi-stakeholder model more robust, we will need to provide reassurances that each of the bolts that make the model churn fulfills its role. Ensuring the nonprofits operating as representatives of civil society are autonomous and are perceived as autonomous will be key to that end.

-

With thanks to participants of the RightsCon workshop, in particular Brandon S., who also provided feedback on this piece.

-