Following the news cycle feels like being caught up in a whirlpool of destruction. From televised genocide to environmental catastrophes, humanity seems to be spiraling towards an inevitable painful end. Money is King. The task of saving the planet seems gargantuan. Project “colonize, dominate, and extract” appears unstoppable. The solutions offered by science and technology feel madly optimistic at best and violently exclusionary at worst. As a writer and performer whose work is rooted in excavating Indigenous ways of knowing and elevating African voices, I question what role the arts can play in offering an alternative and hopeful vision. How can humankind go back in order to move forward?

Throughout history, there has been a deliberate erasure of Indigenous knowledge and practices, creating a collective amnesia that prevents us from seeing that a different way does exist. In a 2015 interview, Kenyan author and academic Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o spoke of the effects of colonization on the colonized: “You erase the memory of who they are, their memory of their past, their memory of being as a people, and after erasing that memory you plant another one, the memory of the colonizer or the memory of the one who is dominating, and then the memory of the colonizer becomes the beginning of your memory.”

A consequence of this is that communities end up “forgetting” their own ways of being on this earth—ways of communing with each other and Mother Nature that are rooted in respect, justice, and equality. Sankofa can serve as an important guide as humanity grapples with the challenges of our times. It’s an Adinkra symbol that signifies learning from the past, meaning “to retrieve” in the Twi language of Ghana. And it is perhaps even more relevant today than it was in the 1800s when it was developed by the Gyaman people of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Recovering ancestral knowledge and practices can yield ways to replace a system that cannot be fixed.

Theater, justice, and environmental knowledge production

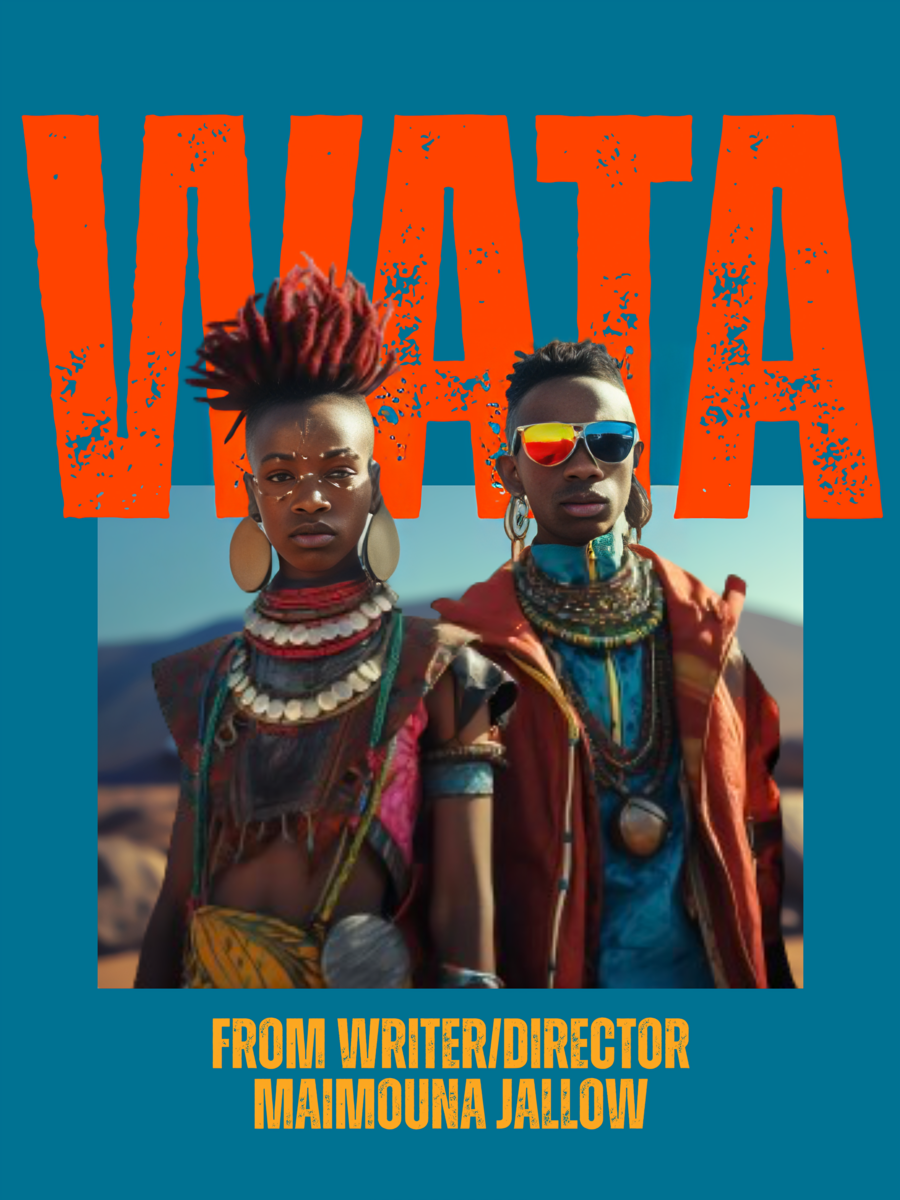

This idea informs a large part of my work. In WATA, the new play that I’m currently developing with support from the NYU Centre for Human Rights and Global Justice, 14-year-old twins Oumou and Omar go on a mission to save their drought-ridden community from total environmental annihilation after their river is sold to foreign investors. Primarily aimed at middle and high school students, the play follows the protagonists as they transition through the three spheres of existence found in Yoruba cosmology—the world of the living, the world of the ancestors, and the world of the unborn. In each, they meet truth-sayers.

In the land of the ancestors, they inadvertently join a gathering of real-life revolutionaries—urban griots like Wangari Maathai, Maya Angelou, and Thomas Sankara. They talk about the ways in which they fought for freedom, how they cared for the environment, and the meaning of community. Drawn from archival records of their speeches and interviews, their words can take on renewed meaning in the contemporary context of the play and become part of a collective re-memory as characters on stage. As actress Viola Davis said in her 2022 interview on the US TV show The View: “You need to see a physical manifestation of your dream. There is something about seeing someone who looks like you that makes it more tangible . . . it gives you the possibility to look through your imagination and redefine yourself.”

I deliberately center revolutionary Black women and men within the field of racial, social, and climate justice to bring the discourse about human and environmental rights closer to home. Ultimately, it’s about countering the harmful narratives that still dominate both African and Western education systems—narratives that erase the agency of Indigenous peoples and teach that Black history began with slavery and colonialism. As former Kenyan Chief Justice Willy Mutunga put it, “We must diversify who we learn from. We must domesticate what we learn.”

In WATA’s story about a quest to save the planet from drought, the connection between humanity, the divine, and nature is key. This connection is embodied in the play through the Orishas, deities also from the Yoruba religious tradition, particularly Ọṣun, the river goddess. As the anthropologist and African Studies scholar Dr. Marimba Ani says, “The African concept of spirituality deals with nature, the metaphysical realities, and the forces that interact in our lives. That’s why your mother would say a prayer when she is planting a flower because she understands this as an energy source. She doesn’t have to articulate it but live it.” Orishas also represent the resilience and adaptability of humans in the face of brutality, with stories that survived the transatlantic slave trade and found new meaning in the Black Diaspora.

Another key theme of the play is justice. At the end of the play, when the “baddies” who sold the river are caught, they are not punished by being excluded, imprisoned, or harmed. Instead, they are brought back into the fold of the community and given an opportunity to atone and contribute to positive change. Young people are thereby invited to reflect on retributive and restorative justice.

Un-coding the lessons of the past

As custodians of the earth, young people can’t afford to be bleak about the future. I’d like to imagine that this work, alongside the work of many of my contemporaries in the arts, can be part of a larger education project that seeks to prepare young people for the future they face. Theater can be used as an access point to begin to explore Indigenous and ancestral knowledge and practices, to “retrieve” and un-code the “language and lessons of the past” and learn from them. Sankofa. It can challenge the Eurocentric lens through which history is taught and center “othered” voices. It can make seemingly complex questions around rights and environmental stewardship more accessible, especially to young people.

I recently came across an Instagram reel in which Nigerian musician Seun Kuti said, “The hope is to end oppression—not to become the new oppressor. The oppressor cannot do it. Anyone who benefits from the system cannot do it.” Ultimately, the hope is to draw on Indigenous legacies and create stories to inspire a new generation, those outside the system, to be active citizens who advocate for rights and challenge oppression.