Next year will mark the 30th anniversary of the 1993 World Conference on Human Rights. The Conference was a milestone in propelling a ‘domestic institutionalization’ dynamic in the field of human rights, which aimed to enhance the implementation of rights through the promotion of institutional innovations at the national level. Its final Declaration notably endorsed the establishment of national human rights institutions and put forward a new concept of ‘National Human Rights Action Plans’ (NHRAPs).

While national human rights institutions propagated widely around the world in the 1990s, and are the subject of a wide array of practical guidance, (soft) law, and scholarly inquiries, NHRAPs met a different fate. By 2003, only twenty countries had adopted a plan. Following frustrating experiences with such plans, OHCHR and UNDP deprioritized their active promotion of NHRAPs in 2002 and, save for a Handbook on NHRAPs that OHCHR published that year, did not invest in producing further guidance.

Since then, accounts on NHRAPs diffusion have been outdated or partial, implying that NHRAPs are a marginal phenomenon. New research published by the Danish Institute for Human Rights corrects this misconception. Based on a comprehensive data collection effort, it reveals that at least 141 such plans have been adopted in 76 countries since 1993. As such, state engagement with NHRAPs is far more significant than accounted for thus far.

Increasing engagement of states with NHRAPs

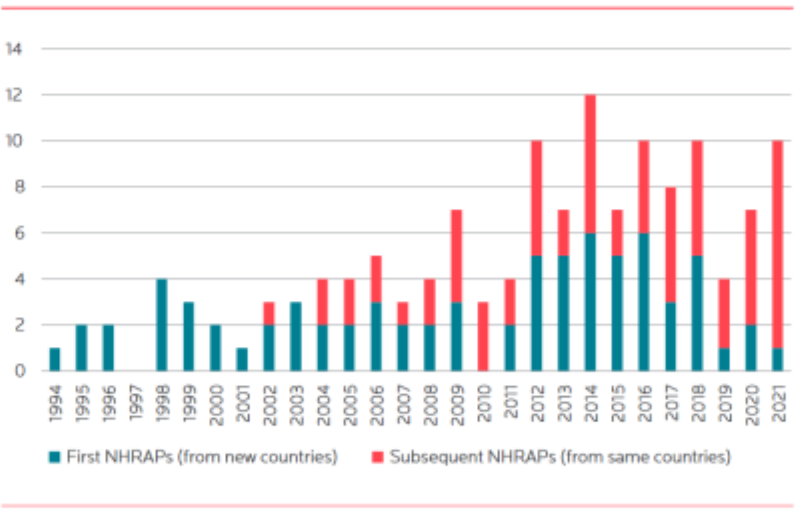

The new inventory of NHRAPs confirms that adoptions of NHRAPs were indeed limited until 2012—creating a long-lasting narrative about NHRAPs’ restricted use. However, two qualitative leaps occurred in the evolution of state practice, represented in the chart below.

Number of NHRAPs adopted each year since 1993

Source: S. Lorion, National Human Rights Action Plans: An Inventory (Part 1: Norm Diffusion and State Practice), DIHR 2022, page 30.

The first leap was in 2002, when some countries started to adopt subsequent plans. Today, adoption of NHRAPs appears institutionalized in an increasing number of countries. For instance, Armenia, Bolivia, China, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Indonesia, Mexico, Moldova, Nepal, Peru, the Republic of Korea, and Thailand all appear to have routinized the adoption of NHRAPs.

Based on a comprehensive data collection effort, it reveals that at least 141 such plans have been adopted in 76 countries since 1993.

The year 2012 constituted the second rupture point, after which the rhythm of NHRAPs’ adoption accelerated sharply, both in terms of new countries adopting their first plans and in terms of countries adopting subsequent plans. More than half of all NHRAPs were adopted in the past decade. Engagement seems to be on the rise: at least thirteen countries have announced the imminent adoption of a NHRAP, including eight countries for which it would be their first plan.

Apparent norm diffusion paradox

This evolution points to an apparent paradox. States only limitedly adopted NHRAPs when the model was actively promoted by international organizations and supported by guidance and soft law. Yet a majority of them were developed at a time when the tool was deprioritized by such actors. Geographically too, data shows that there was no higher engagement in areas where regional organizations—such as the Council of Europe—advocated for their member states to adopt NHRAPs. Data shows that NHRAPs are roughly equally adopted in many regions of the world, regardless of development status.

One strong hypothesis to explain the surge in engagement with NHRAPs after 2012 is connected to a new type of international oversight by peers, namely the Universal Periodic Review that started in 2008. Since the very first UPR cycle, many delegates recommended that reviewed states should adopt general human rights policies. Countries with NHRAPs consistently recommended other states to emulate this practice. The UPR offered states a platform to express support, and states possibly noticed the relatively easy reputational gains that could result from the adoption of NHRAPs during UPR reviews.

Comeback in international prescription—but same methodology?

It therefore does not come as a surprise that the revival of OHCHR’s references and promotion of NHRAPs—after fifteen years of normative silence on NHRAPs—occurred in relation to the Universal Periodic Review. Since 2017, the High Commissioners for Human Rights have systematically recommended, in their follow-up letters to the reviewed states, the development or better implementation of NHRAPs.

However, the concepts and methodologies used for NHRAPs seem to have evolved. Delving into the inventory indeed shows that several recent plans are in fact recommendations implementation plans called NHRAPs. Indeed, during the past decades, international actors had promoted alternative types of planning methodologies. These included a preference for thematic plans specific to human rights sub-fields, ‘recommendations implementation plans’ grounded on international recommendations rather than NHRAPs grounded on lengthy national consultations processes, or mainstreaming human rights into overarching national development plans.

The different imperatives of these planning methodologies may prove difficult to reconcile. For instance, the UN Secretary General explained in detail how NHRAPs and recommendations implementation plans are ‘fundamentally different.’ As UN methodological guidance on NHRAPs has not been updated since the 2002 OHCHR Handbook, conceptual ambiguities have increased. These unarticulated approaches leave states dubitative as to what NHRAPs are and how they should be developed and may exacerbate the wide heterogeneity that already characterizes NHRAPs in practice, due to local variations resulting from distinctive governance systems, political preferences, contexts, or national consultations.

Further research needed

So far, almost all academics and practitioners have taken the existing OHCHR’s outdated data on NHRAPs as a reference. This has also led norm entrepreneurs promoting other types of human rights planning to predicate their arguments on incorrect assumptions about the diffusion of NHRAPs and to disregard the potential of the, in fact, large pool of past and currentNHRAPs to generate evidence on whether, and in what circumstances, action planning is actually useful for human rights implementation.

Save for three recent research projects by Azadeh Chalabi, the Centre for the Study of Human Rights at Nankai University, and the Latin American Council of Social Sciences, NHRAPs remain blatantly under-researched. NHRAPs require more critical attention. In particular, empirical research would be crucial in understanding how NHRAPs impact the reality of human rights.

NHRAPs have the potential to enhance human rights implementation but are also frequently instrumentalized for other purposes. They may, for instance, distract national and international accountability strategies or redirect civil society efforts into state-led bureaucratic processes. As NHRAPs have recently been revived by the UN as an 'essential element' of national human rights systems and as more states are developing plans, this research intervention is not only timely: it is urgent.