According to a recently published report, many New Zealanders are unable to enjoy even the most basic levels of the right to housing. Earlier this year, the Human Rights Measurement Initiative (HRMI), hosted by New Zealand economic research institute Motu took a deep dive into the right to adequate housing in Aotearoa (which is the Māori name for New Zealand) to measure whether the New Zealand government is taking the necessary steps to fulfil its international human rights promises. This research was commissioned by the New Zealand Human Rights Commission.

Successive New Zealand governments have indeed committed to human rights standards in international human rights treaties. There are five key promises that come with this commitment: the minimum core obligations, progressive realization, non-retrogression, to use the maximum of available resources, and non-discrimination. In the area of housing, these promises reflect the government’s commitment to guarantee basic shelter and housing to all its people, and to ensure all available resources are used to continually improve every aspect of the right to housing over time. The government is also making an explicit promise that the right to housing is to be enjoyed by everyone, regardless of their demographic or socioeconomic status.

The report provides new methodologies for measuring whether the government is living up to these five international human rights promises, explained in the steps below.

First, the right to housing is divided into six key themes: security of tenure, how liveable the house is, housing affordability, whether enough houses exist, the suitability of housing services and infrastructure, and housing location.

Second, after looking at publicly available data on housing outcomes in Aotearoa, indicators are created within each housing theme. These indicators are used to measure how well each aspect of the right to housing is being experienced by all people. For example, within the housing affordability theme, we created an indicator measuring the percentage of people that own their own home.

Third, methodologies are created for measuring the government’s performance on each human rights promise. Each methodology identifies the type of data needed to measure whether the promise is being fulfilled.

Fourth, indicators are matched with methodologies to assess New Zealand’s efforts toward achieving each of its human rights promises within each right to housing theme.

The New Zealand government is failing to fulfil its promises for the right to housing

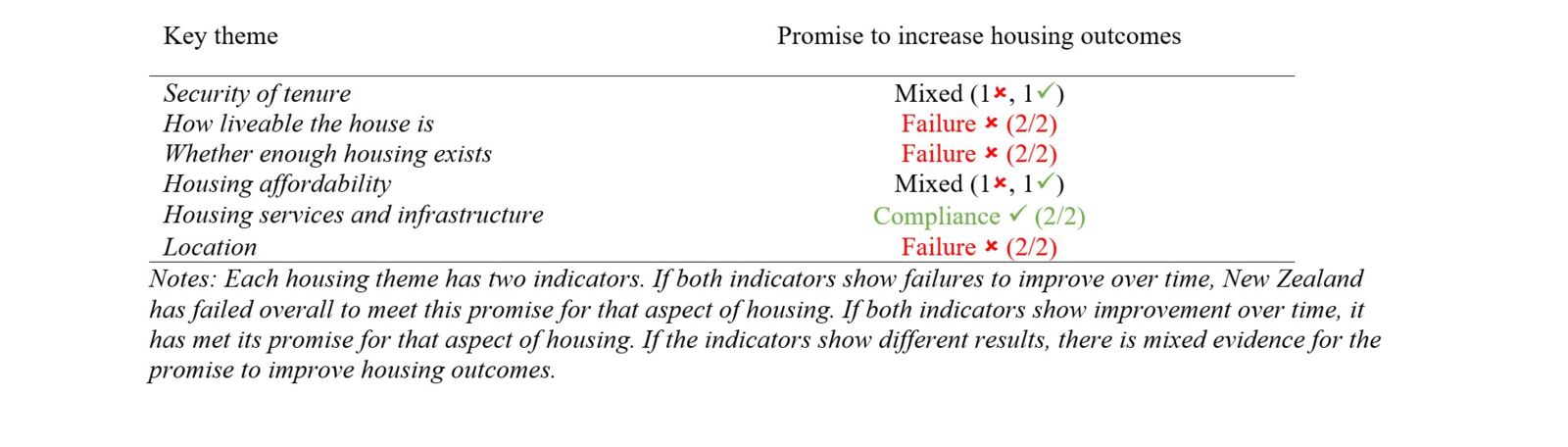

Housing outcomes have not improved in Aotearoa for a very long time. Table 1 summarizes the different ways the New Zealand government is not meeting its promise to improve housing outcomes for everyone (‘progressive realization’).

Of the dozen right to housing outcomes that we can track over time, eight have failed to improve. The number of people living in healthy homes has not increased and the number of people that are unable to access houses is growing, meaning more people are becoming homeless. This also demonstrates a failure to meet the minimum standard of housing.

Table 1. Results for the promise to increase housing outcomes in Aotearoa

Additionally, of the 11 housing outcomes we can compare across population subgroups, nine show clear breaches of the promise to provide the right to housing in a non-discriminatory way. New Zealand’s current housing market situation makes achieving favorable housing outcomes more difficult for Māori, Pacific Peoples, disabled people, people with low or no qualifications, the unemployed, and people from lower socioeconomic areas.

In accordance with the government’s promise to use the maximum of available resources to ensure housing outcomes are improving over time, both indicators suggest more can be achieved, given New Zealand’s current per capita income level, for providing housing services and infrastructure to all. By comparing New Zealand’s performance on these right to housing indicators to that of other comparable high-income OECD countries, results suggest policy insights can be gained from countries such as Finland, Germany, Iceland, Korea and the United Kingdom, who are currently outperforming New Zealand.

Urgent action is needed to improve housing outcomes

Now that we have the methodologies for assessing the government’s performance against each of their human rights promises, we have a clear understanding of the many different ways the New Zealand government is failing to ensure the right to housing for everyone. Identifying where human rights violations are occurring within the right to housing shows the government where change is most urgently needed. Housing policies, strategies, and resources must be updated to prevent further human rights violations, particularly for protecting people against homelessness and ensuring that, once people are housed, the homes are warm, dry, and free of mold. Since all economic, social and cultural rights are interrelated, improving housing outcomes will also boost other human rights outcomes, such as the right to health care and protection (also evaluated in the report).

Overall, this exercise shows that human rights aren’t just aspirations, they are international commitments for which performance can be assessed. This is the first step for holding the New Zealand government to account and ensuring human rights are taken seriously. If the government acts urgently to rectify the violations identified in the report, we will be one step closer toward achieving a thriving society with economic, social and cultural rights flourishing for all.

Want to know how your country is performing?

Other countries can use the methodologies laid out in the report discussed to empirically measure whether their government is meeting its human rights promises. In doing so, more governments can realise their failures and redirect their policy strategies and resources to most efficiently improve human rights outcomes for everyone. Check out HRMI’s Rights Tracker to see how your country is keeping its human rights promises, including on the right to housing.