In August 2021, a bill was tabled in Tonga’s Parliament to introduce the death penalty for drug offences. Because Tonga is a small archipelago country in the Pacific, the implications of this regressive development to the global human rights debate were therefore easy to dismiss.

This is a concerning shift because although there is already a death penalty in Tonga for murder and treason, the last executions occurred in 1982. The introduction of a new cause for death penalty certainly demonstrates the potency of the war on drugs narrative to resurrect the desire for it after nearly four decades of de facto moratorium.

It also confirms the paradox of the global state of the death penalty. Since the 1970s, there has been a growing trend towards abolishing the death penalty for all crimes. However, more countries have passed legislation imposing the death penalty for drug offences. In 1979, it was estimated that only 10 countries prescribed the death penalty for drugs. By the year 2000, the numbers of countries had risen to 36.

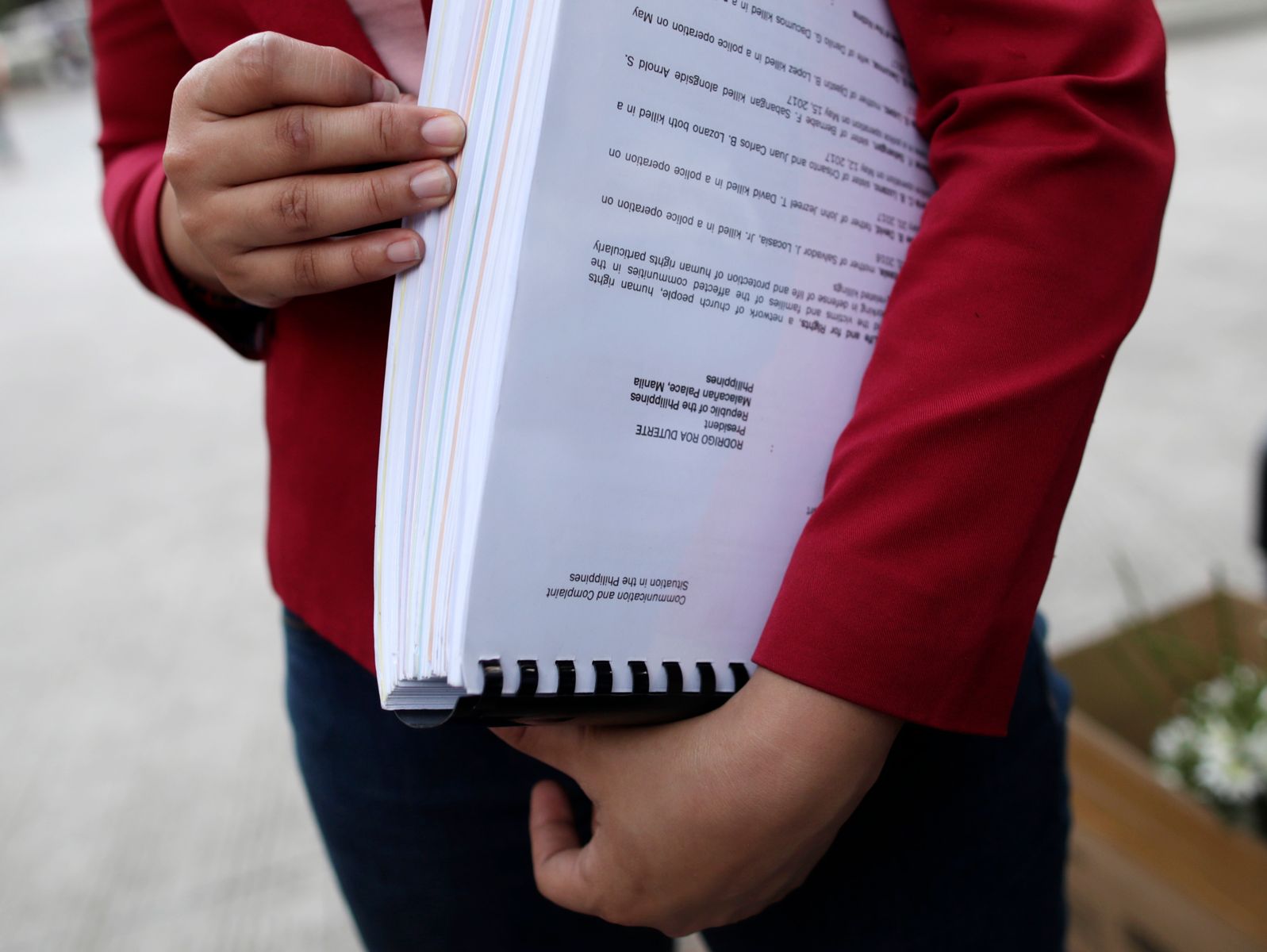

Tonga’s recent passage is not an isolated phenomenon. Bangladesh expanded the application of the death penalty to new drug offences in 2018. And a year later, President Sirisena of Sri Lanka announced the signing of a death warrant for four drug convicts—a move that was largely inspired by President Duterte’s bloody drug war in the Philippines. If the execution was resumed, it would put an end to a 43-year moratorium on executions in Sri Lanka. Earlier this year, a bill that would reinstate the death penalty for drugs was adopted by the Philippines’ House of Representatives.

Since the 1970s, there has been a growing trend towards abolishing the death penalty for all crimes. However, more countries have passed legislation imposing the death penalty for drug offences.

Human rights groups have repeatedly argued that drug offenses do not fall into the category of ‘the most serious crimes’ for which the death penalty may be permitted under international human rights law. Yet the death penalty for drug offenses appears to be on the rise, and it remains one of authoritarian leaders’ preferred tools for garnering popular support and quelling dissent. What are some possible solutions to this troubling proclivity?

In most jurisdictions where the death penalty for drugs operates, retentionist arguments normally revolve around two major points: deterrence effect and public opinion. I would say that there is no such thing as deterrence. A rational choice theorist would probably argue that if chances of being arrested and/or convicted are low, or even if the risk is high, but the benefit of committing such crimes outweighs the costs, rational offenders will commit the offenses regardless of the severity of punishment. In some of these retentionist countries, offenders can even bribe the law apparatus to prevent the possibility of being sentenced to death. Nevertheless, there are not enough rigorous studies to prove that the death penalty works to curb drug offences.

Meanwhile, on the question of public opinion, retentionist governments tend to rationalize their position, citing high levels of public support for punishing measures. They usually rely on polls conducted by mainstream media in which the question is a simple “yes” or “no.” Anywhere in the world, including in abolitionist countries, for example in the United Kingdom or France, if people are asked whether they are in favor of the death penalty or not, they would incline to say “yes.” However, this simple binary question masks the complexity of the death penalty.

A recent public opinion study in Indonesia, carried out by Oxford University, reveals interesting and significant outcomes. Almost 70% of the respondents expressed support for the death penalty. However, only 2% of respondents were well-informed and only 4% were very concerned about the issue. The study also revealed that 54% of death penalty supporters believed it would deter drug offenses. But when asked which measures are most likely to reduce drug crimes, the vast majority chose more effective policing, better education for the next generation, and social measures to alleviate poverty. Only a few mentioned more death sentences and execution. When respondents were presented with realistic scenario cases, only 14% supported the death penalty for drug trafficking. Public opinion studies in Trinidad (2011), Malaysia (2013), Japan (2015), and Zimbabwe (2018) all yielded similar results. The findings of all these reports imply that, on a broad level, public support for the death sentence for drug offenses is strong, but this support is based on a lack of understanding. When confronted with real-life examples, public support for the death penalty plummets, and the public becomes increasingly open to alternatives to the death sentence.

More robust studies that investigate the issue in greater depth and generate a more nuanced and sophisticated knowledge of the issue are thus needed to definitively refute the deterrence and public opinion arguments. This type of research, however, is costly. More donors and abolitionist states should support this project and the subsequent advocacy strategy, so that local civil society can effectively utilize it to further the abolition agenda.

When confronted with real-life examples, public support for the death penalty plummets, and the public becomes increasingly open to alternatives to the death sentence.

Although adequate resources to support research projects are available, abolition of the death penalty will not occur overnight. A critical component to help disempower the death penalty regime should be strengthened: legal representation. Almost everyone on death row for drug offenses is a poor and vulnerable person exploited by the syndicates. Early and competent legal assistance from the time of arrest can be a life-saving means for people facing the death penalty.

Unfortunately, despite the presence of qualified human rights and criminal defense lawyers in many death penalty jurisdictions, only a few lawyers are willing to brave the stigma and represent drug defendants facing death penalty charges. Even if there are lawyers available to assist persons facing the death penalty, they are usually underfunded. Because the less likely it is for judges to impose death sentences, the more likely it is that we will achieve a de facto moratorium, paving the way for abolition. At the end of the day, more efforts to support, build capacity, and sensitize lawyers are required.

Finally, when pressed with questions on how to address drug trafficking, human rights advocates should be able to articulate alternatives to the death penalty. It is important to assert that the death penalty is ineffective in deterring illicit drug trade. However, as we have seen with the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and now Tonga, articulation alone is insufficient. How do we tackle the so-called drug problem in a way that does not perpetuate and extend drug prohibitionist premise?

To answer that, we need an open and honest public debate about drugs, drug use, and the illicit drug economy, beyond “just say no.” We can begin by destigmatizing drugs and questioning the rationale for the drug war. Only then will we be able to move closer to our goal of abolishing the death penalty for drug offenses.