The climate crisis disproportionately affects women and children. Climate change has been described as “a major stressor causing poor pregnancy outcomes and child development.” Extreme heat attributable to climate change is a key mediating factor.

Poor pregnancy outcomes due to hot temperatures include stillbirth and preterm birth before the completion of 37 weeks of pregnancy. Preterm birth can result in irreversible consequences over a child’s lifetime, including, for example, in relation to the cardiovascular system and cognitive development. What remains often under the radar in this context are the long-term effects of adverse birth outcomes, both on women and on children, affecting children’s well-being in adulthood.

These effects could be prevented if governments were to mitigate climate change and help women adapt to heatwaves by providing the necessary health infrastructure for prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal care.

There is no time to lose. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is unequivocal: “Climate change is already affecting every inhabited region across the globe, with human influence contributing to many observed changes in weather and climate extremes.” Hot temperatures (including heatwaves) have increased at the global scale since the 1950s, as the IPCC report clearly shows.

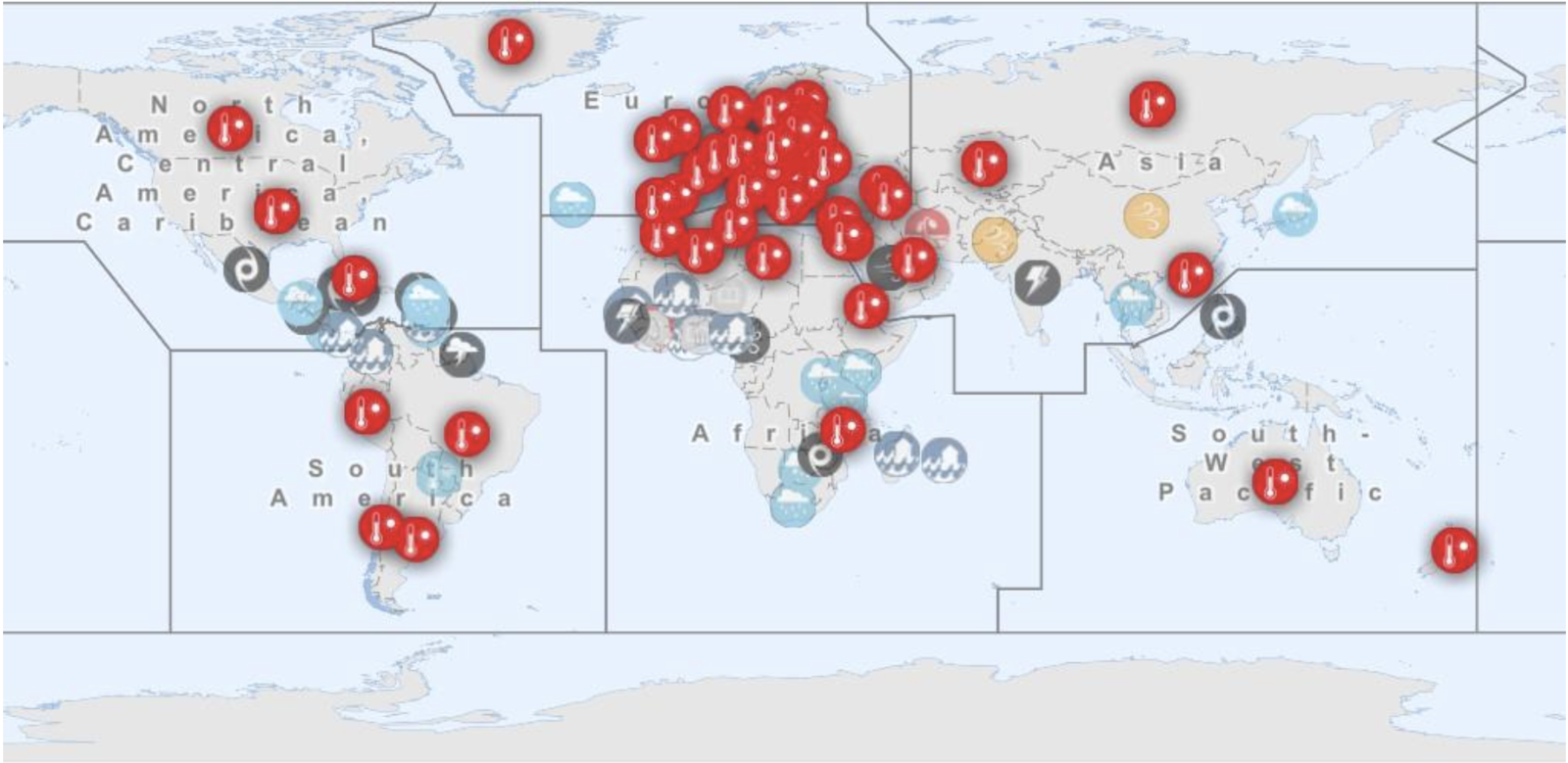

The report also manifests high confidence that human-induced climate change is the main driver of the observed changes in most inhabited regions. In 2021 alone, 86 heat waves were reported worldwide, according to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

There were 86 heatwaves reported in 2021. Source: WMO, Extreme Events in 2021.

Pregnant women are disproportionately at risk of being affected by heat and heatwaves. Research offering evidence from industrialized as well as from low- and middle-income countries is compelling in this regard. The impact of heat on pregnant women is undeniable and compounded, for example, by air pollution and poverty (low socioeconomic position). Environmental epidemiologist Sara McElroy and a team of climate researchers offer a global analysis across fourteen lower-middle income countries while maternal health expert Matthew Francis Chersich and an international team of thirteen specialists in public and environmental health supported by twelve collaborators of a Climate Change and Heat-Health Study Group focus primarily on developed countries.

The distinct vulnerability of pregnant women makes the impact of unmitigated anthropogenic global warming a question of discrimination as states fail to protect women from the risks of heat exposure. The first human right affected is the right to life as adverse birth outcomes can also result in stillbirth or maternal mortality. Furthermore, the vulnerability of preterm children and their disrupted development brings a child’s right to a healthy development to the fore, and the corrosive effect of high temperatures on pregnant women likewise implicates their right to health.

Other rights concerned are the right to a healthy environment, the rights to safe motherhood, and the right to family life. These rights fall within a state’s responsibility and the corresponding obligations to take action and climate action (e.g., mitigation and adaptation), at least as far as states have agreed to under the Paris Agreement.

The preamble of the Paris Agreement, moreover, acknowledges that State Parties should, “when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of indigenous peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the right to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.”

Related human rights such as the right to an adequate standard of living are given legal effect in international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

We have evidence to support rights-based climate responsibility vis-à-vis pregnant women from three areas. First, from climate change creating hot extremes. Second, from heat extremes leading to preterm birth and other negative birth outcomes. For example, there is an association between extreme heat and preterm birth in Harris County, Texas, USA. There is also a link between ambient temperature and preterm birth in New South Wales, Australia. And third, as for the long-term consequences of preterm birth, evidence shows that people born preterm carry a significantly higher risk for cardiovascular and renal malfunctions at young adulthood.

The outcomes highlighted by these studies point to the failures of states to meet their human rights obligations, to guarantee the rights of pregnant women, and protect pregnant women from indirect discrimination as their distinct vulnerability is not recognized.

Just as glaciers are irreversibly melting due to climate change, the impact of heat on pregnant women and their children may turn out to be irreversible and entail a diminished quality of life for adults affected and more costs for society to take care of related adult disease. As a result, lawmakers and policymakers must urgently recognize the rights of pregnant women exposed to high temperatures due to climate change.

These effects could be prevented if governments were to mitigate climate change and help women adapt to heatwaves by providing the necessary health infrastructure for prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal care.

There is also an urgent call to support pregnant women farmers in the Global South who may experience heat stress as well as exposure to droughts and armed conflict. Their risk of suffering adverse birth outcomes is even higher.

Crucially, extreme heat is just one, albeit a well-researched, consequence of climate change affecting pregnancies—next to wildfires, floods, and droughts that might similarly influence pregnancy outcomes and result not only in preterm birth but also in pregnancy loss, restricted foetal growth, and low birthweight.

What needs to be done? According to perinatal health expert Sandie Ha, a “successful solution should involve close collaboration of interdisciplinary and multilevel bodies including the government, community partners, the public, physicians, industry partners, public health practitioners, and researchers.”

And as environmental judge Brian Preston and human rights scholars Julie Fraser and Laura Henderson remind us, human rights advocates have a responsibility too: to be aware of the reality of climate change, how it interacts with human rights, and how we can shape (human rights) law and contribute to climate justice—and we must add, climate justice for pregnant women and their offspring.