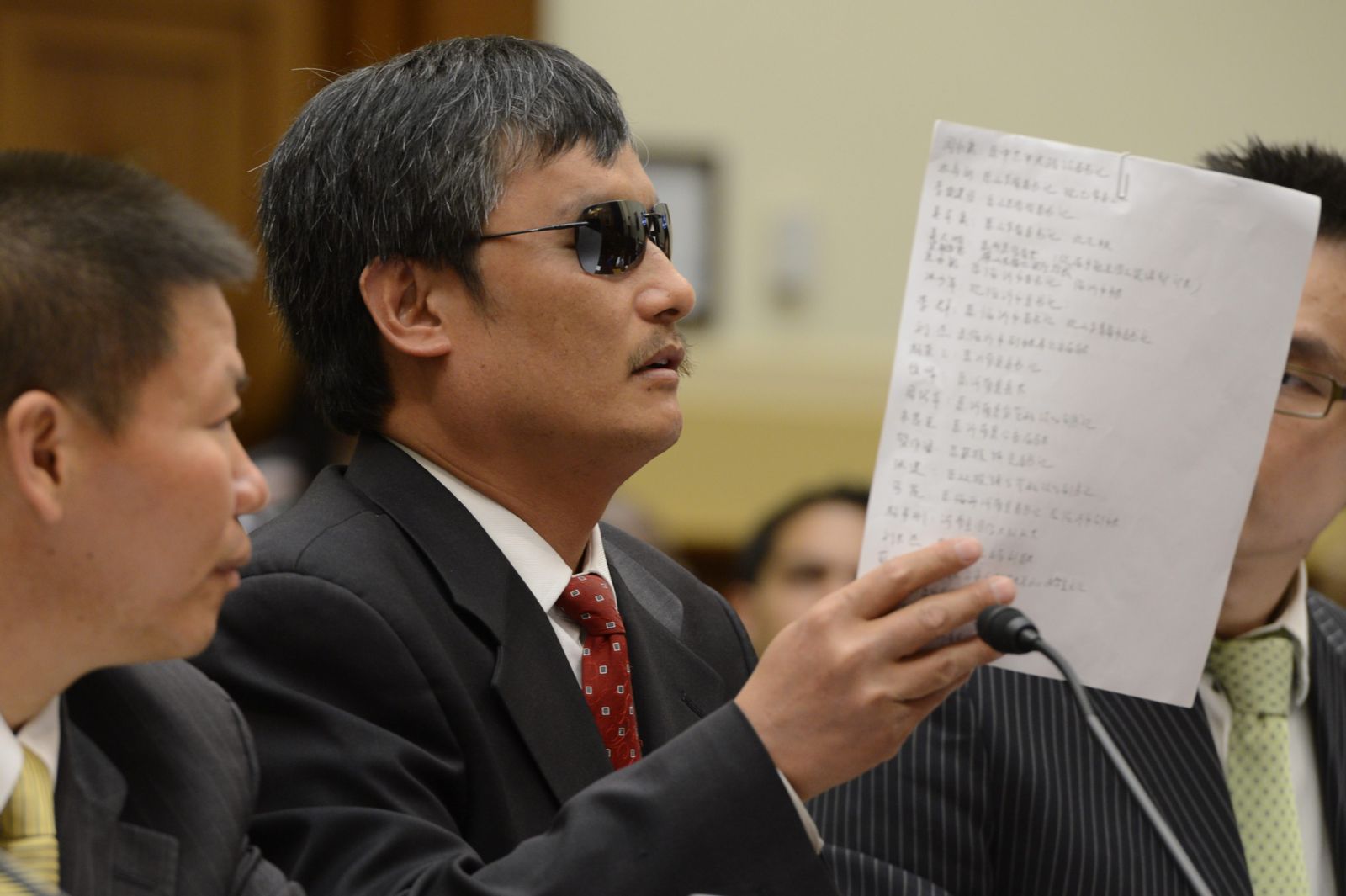

Photo: EFE/EPA Michael Reynolds

Rather than a set of teachable skills, strategic litigation is the talent to turn a social problem into a vision of an actionable court case. When strategic litigation is aimed at defending human rights, its political meaning varies from society to society. The integrity of the justice system and judicial culture are the most important factors to be taken into account when investing in strategic litigation.

But with majoritarian illiberalism on the rise in so many regions of the world, is it still sensible for human rights advocates to engage in strategic litigation to fight rights abuses? Particularly when strong political constrains amplify the challenges coming from the justice sphere? My answer is emphatically positive. “When the going gets tough, the tough get going” is an adage that might have been created with human rights lawyers in mind. Despite its well-known inherent limitations, litigation is even more important in hostile political climates, for several reasons.

First, it may restrict illiberal power. At first glance, the apparent tension between majority rule and the rule of law means that when populists are in charge, the courts should push back. However, populism itself obscures real power relations – after all, populist leaders are usually themselves members of the power elite. The actual political role of the courts as well as the law as such, regardless of the political regime, is to both legitimize and limit power. While justifying and guarding the status quo, the law and the courts also at the same time restrain power to some extent, curbing its propensity to become absolute or arbitrary. The legal defence of human rights, by serving the most deprived or disadvantaged members of society, fulfils the restraining role of the law.

For example, in Bulgaria, a semi-consolidated democracy that has been sliding back in recent years, a court ruled against the current deputy prime minister, Valeri Simeonov, for virulent hate speech against Roma, in a case litigated by the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee. In another recent example, a court in Hungary repealed the decision of the Hungarian Immigration and Asylum Office which allowed the use of psychological testing in determining an asylum seeker’s sexual orientation.

Second, strategic litigation contributes to educating the public by raising awareness of human rights, which is desperately needed in illiberal environments. Indeed, over the last decade, in Central and Eastern Europe, including Russia, there has been measurable progress in public awareness of human rights despite the surge of illiberal politics and the authoritarian trends in the region. Human rights lawyers notice that cases they file often motivate numerous similarly placed individuals to actively seek justice for themselves. For example, prisoner rights and the rights of persons with disabilities have seen marked improvement in the region due to such litigation from wronged individuals. Even in illiberal regimes, litigating on certain issues—even if it repeatedly fails—can create and channel pressure leading to a legal or political solution at some later point.

Third, despite the weakness of international law, decisions of international tribunals still matter on the ground. In Central and Eastern Europe, for example, a significant proportion of the advances in rights protection can be credited to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). One may be misled by the prevailing nationalist rhetoric in the region to believe that this is no longer the case, but a careful analysis would show the ECtHR has had a real impact.

Fourth, judges’ minds are not impervious to change. When a well-founded claim is made repeatedly, judges often come around and depart from entrenched jurisprudence. This evolution has its own dynamic and is by no means directly related to political developments. Perhaps this is why last October a recent landmark blasphemy case in Pakistan made the headlines, as the Supreme Court struck down the death sentence of a Christian woman. Earlier, in September, the Supreme Court of India decriminalized homosexuality crowning more than ten years of intense legal advocacy by the LGBT community. Human rights litigation challenges the judiciary at the level of their professional and human integrity. One day, a judge finds that their professional honor, a higher loyalty of sorts, compels them to rule in favour of human rights.

Fifth, whatever human rights lawyers may feel about the possibilities for success, it is sometimes the victim who urges them to choose litigation. Perhaps every human rights lawyer can tell a story about that unyielding person who pressed on, against all the odds, motivated more by the need to defend their human dignity than by whether the case was winnable. There is something irresistible about a victim in search of justice. Even if the independence of the judiciary is severely compromised, or conditions are otherwise hostile, taking on their case may be a duty too powerful to ignore.

Finally, legal action in search of justice is simply the right thing to do. This alone should motivate our support for litigation, perhaps especially in backsliding democracies or closed, repressive societies. The moral argument for strategic litigation is akin to the dissident attitude under communism, which demanded that the dissident behave as if there existed freedom and the rule of law.

One of the most heartening discoveries I have made during my travels within closed societies is that some lawyers took huge personal risks, entirely irrespective of whether external supporters existed. They took action because this is who they were. Moreover, filing a lawsuit in defence of human rights in a broken democracy or a repressive closed society is not just the right thing to do; it is an act of exercising symbolic power that the oppressors dread most. Persons like Gao Zhisheng, the human rights lawyer and author, whom the Chinese authorities have persecuted relentlessly, are the ultimate answer to the question of whether human rights litigation still matters when the going gets tough.