Recent technological advancements such as reusable spacecraft and 3D-printed launch vehicles have accelerated the possibility of multiplanetary existence, fueling a private-company space race to send humans to Mars by 2030. According to SpaceX’s CEO, Elon Musk, there may be about one million humans living on the Red Planet by 2060.

While the colonization of Mars remains hypothetical for now, the possibility of multiplanetary existence raises fascinating questions about the universality of the human rights framework and, more specifically, the human rights obligations of private companies on Mars.

These questions are complicated by statements contained in a SpaceX legal agreement recognizing “Mars as a free planet” and asserting that “no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities.” If corporations like SpaceX argue that governments lack authority over what happens on Mars, then what human rights obligations will these businesses have toward Martian settlers?

The extension of human rights protections on Mars must be considered in relation to the corporatization of multiplanetary existence. Anthropologist Kimberley D. McKinson warns about the colonization of Mars by private entities such as SpaceX, arguing that “these corporations are at risk of effectively continuing Earth’s most violent colonial legacies by replicating them in outer space.” Juan García Bonilla, who studies space exploration, is similarly troubled by the role of private companies in space exploration, suggesting that certain rights in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) could be threatened.

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, which is responsible for assisting countries in leveraging the benefits of space, has yet to offer any guidance on the applicability of human rights in space or on Mars. In its most comprehensive publication on international space law, there is one reference to human rights, but this is limited to international direct television broadcasting by satellite.

Consequently, there is little consensus about the business and human rights implications of multiplanetary existence. However, researchers appear to make two assumptions about this topic: first, that the human rights framework can and should be extended to Mars and, second, that private companies have some responsibility for respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights on Mars.

But the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights provide that businesses are only required to respect human rights. And, while states have an obligation to ensure that corporations do not violate human rights, this obligation is generally limited to the state’s jurisdiction or territory. The Guiding Principles indicate that states are “not generally required under international human rights law to regulate the extraterritorial activities of businesses,” but neither are states “prohibited from doing so.”

In General Comment 24, the extraterritorial obligations of states under the International Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) “arise when a State party may influence situations located outside its territory … by controlling the activities of corporations domiciled in its territory and/or under its jurisdiction.” These state obligations to regulate extraterritorial corporate activity are helpful.

However, the Guiding Principles and the international human rights framework more generally offer no guidance on how governments could monitor activities on Mars and take the necessary action to address human rights violations. Furthermore, since many of the corporations that plan to travel to Mars, such as SpaceX, Blue Origin, Impulse Space, and Relativity Space, are based in the United States, it is unlikely that the US government will comply with General Comment 24, since it has not yet ratified the ICESCR.

In instances where the US has ratified human rights instruments such as the ICCPR, the government consistently argues against the extraterritorial application of the covenant. More recently, the US withdrew from discussions on developing a business and human rights treaty, citing, among others, the treaty’s “extraterritorial application of domestic laws.”

That said, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which funds some of SpaceX’s Mars exploration project, has a policy document stating that “Work on NASA cooperative agreements is subject to the provisions of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.” NASA’s policy document on Cooperative Agreements with Commercial Firms references Title VI’s prohibition of discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in any program receiving government funding. While this suggests that the US government has an obligation under Title VI to ensure that SpaceX complies with the Civil Rights Act, the title refers specifically to “no person in the United States.”

While these provisions are limited and do not ensure human rights protections for multiplanetary settlers, they point to the government’s potential capacity to regulate corporate activity in the US as it pertains to work on Mars. But, given the US opposition to the extraterritorial application of human rights treaties, combined with SpaceX’s assertion that “no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities,” the likelihood of US-based corporations protecting and fulfilling human rights on Mars remains ambivalent.

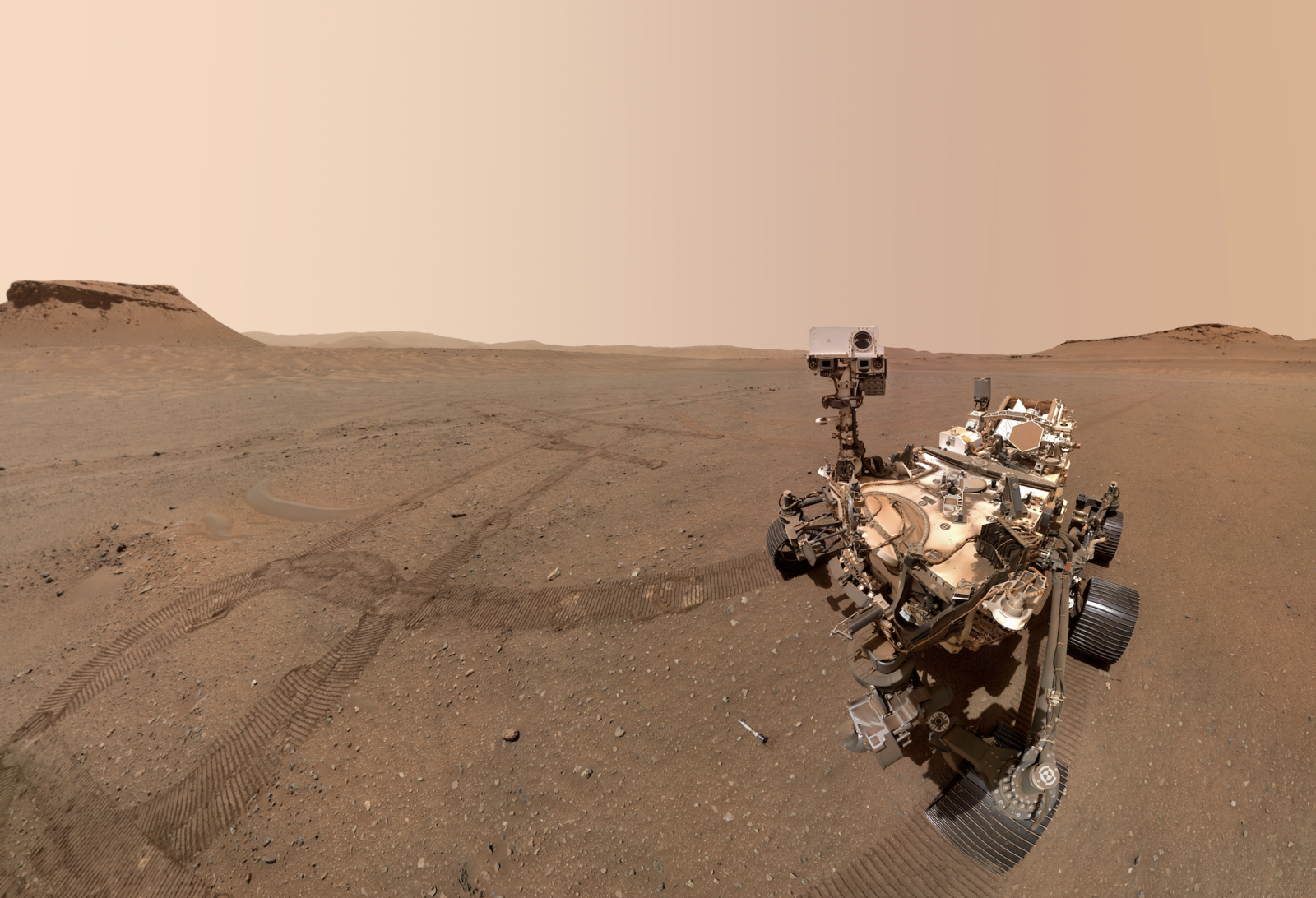

Despite recent setbacks to launch SpaceX’s most powerful rocket, the challenges presented by future multiplanetary existence are not simply an intellectual exercise. Corporations, rather than the state, have historically been at the frontier of colonization. For instance, the Dutch West India Company “took a leading role in establishing colonies” during the fifteenth century.

Recognizing that corporations are leading efforts to colonize Mars, which is likely to be realized within the next few decades, attention must be given to the role played by businesses in shaping a multiplanetary future. Human rights offers a framework that can inform multiplanetary existence while simultaneously advancing mechanisms that strengthen corporate accountability.