How important is international funding to local human rights groups worldwide? Oddly enough, there has been little published research on the topic. Pressured by angry nationalists and vengeful governments, human rights activists and donors prefer to keep money questions out of the spotlight.

Indeed, we know of only two existing studies. In 2006, a Nigerian scholar published research on 20 of his country’s 100 human rights groups, the vast majority of which were foreign-supported. Two years later, Israeli researchers published a study based on interviews with 16 of the country’s 26 human rights groups, and said that more than 90 percent of their budgets came from Europe and the United States. Neither study, however, shed light on conditions elsewhere in the world.

To rectify this gap, we began by interviewing 128 human rights workers from 60 countries in the Global South and former Communist region. Then we assembled lists of all the local rights groups we could find in Rabat and Casablanca (Morocco), Mumbai (India), and Mexico City and San Cristóbal de las Casas (Mexico). Our team identified 189 groups in total, all of which were non-governmental, domestically headquartered, politically unaffiliated, and legally registered.

Because NGO workers are understandably reluctant to discuss finances with strangers, we began with a general question: In your opinion, what percentage of human rights organizations in [your country] receives substantial funding from foreign donors? We summarize their answers in Figure A below.

Mean estimates ranged from a high of 84% in Rabat and Casablanca to a low of 60% in Mumbai. The Indian and Mexican estimates were statistically indistinguishable, given the closeness in estimates and the small sample sizes involved.

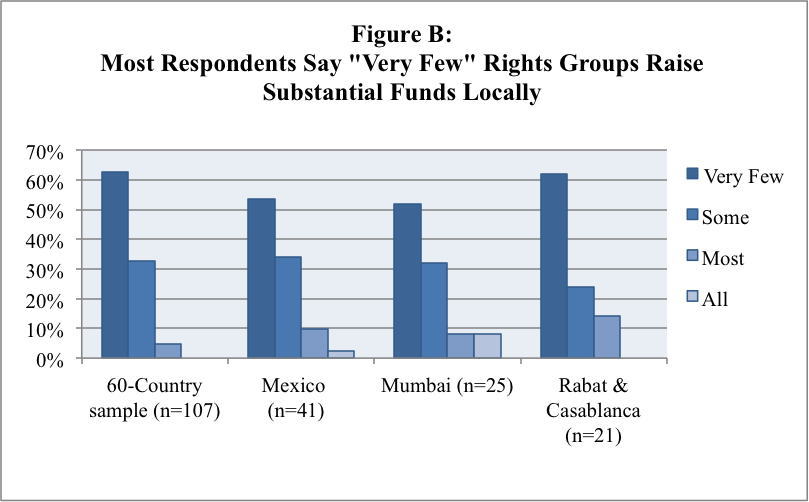

Next we asked respondents: In your view, how many human rights organizations in [your country] raise substantial local funds? We summarize those answers in Figure B below.

“Very few” was the most common response, and the responses were statistically indistinguishable across samples.

We then asked respondents whether their own organizations received foreign funds, and the number of positive responses ranged from 67% to 89% per sample, as summarized in Figure C.

This doesn’t say much about the relative weight of foreign funds, however. Precise budget questions were too sensitive for our face-to-face surveys, but 49 respondents volunteered information on how much of their annual organizational budgets derived from foreign funds. To build on this data, we sent follow-up surveys to all 233 of our respondents, and received details from another 47 persons. We summarize all 96 answers in Figure D below.

In three of the four samples, respondents said foreign funding comprised more than half their organization’s budget. Mumbai was the exception, likely as a result of India’s long-standing restrictions on overseas aid to local organizations.

Why does foreign aid dominate?

Is it poverty?

Many respondents said their countries were too poor to support local rights groups. Upon closer examination, however, this explanation seems unsupported. Consider the above-cited Israeli study, which discovered that local rights groups depend heavily on foreign aid. In 2008, the year that research appeared, Israel’s Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) – adjusted per capita income – was $25,600, ranking it 38 of 180 countries globally. Whatever the reason for Israeli rights groups’ foreign aid dependence, per capita income was not among them. Consider also Figure A: Respondents said that Moroccan rights groups were more likely than those in India to receive “substantial” foreign aid, but Morocco’s per capita income was 25% higher than India’s. And while respondent estimates for India and Mexico were statistically indistinguishable, Mexico’s per capita income was 77% higher than India’s.

Per capita income, it seems, doesn’t explain all that much.

How about culture?

Perhaps ordinary people don’t support human rights groups because they oppose human rights ideas? In Israel, experts say Jewish citizens associate the term “human rights” with Palestinian interests. Given Israeli-Palestinian tensions, aren’t Jewish Israelis simply unwilling to fund their enemies’ allies?

Again, a closer look suggests otherwise. In 2003, an Israeli survey found that 53% of the public thought it was “very important” (20%) or “somewhat important” (33%) to protect Palestinian rights. In 2008, another survey found that 52% of the public thought Israeli NGOs were either “very” (9%) or “somewhat” (43%) reliable sources of human rights information. With this number of supporters in a relatively wealthy country, Israeli rights groups should, in theory, be raising at least some local cash. So why don't they?

Other studies show that human rights ideas enjoy broad support internationally. In 2008, a global consortium asked 47,241 people in 25 countries for their views on specific human rights, including torture, political rights, women’s rights, religious freedom, and economic and social rights. In every country, they found, the norms enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights received “robust support,” as did the notion of United Nations intervention to promote these ideals. Importantly, the survey teams found little support for the notion that people worldwide lived in different moral universes.

Some human rights issues, of course, are particularly sensitive, and are therefore likely to face broad-based popular social or religious resistance; issues of gender, family and sexuality come most readily to mind. Still, our own surveys show that local human rights groups enjoy a fair bit of local support, just as they do in Israel.

Figure E displays the results of our national surveys in Mexico and Colombia, along with our regional surveys in India (Mumbai) and Morocco (Rabat and Casablanca). We asked more than 6,000 people how much they trusted their country’s human rights groups, rescaling their answers from 0 to 1, with the latter representing the highest level of trust.

Human rights groups received reasonably high scores, ranging from 0.43 in Morocco to 0.59 in Mexico. With that kind of domestic support, local rights groups should, in theory, be able to raise some money locally.

So why don’t they?

The reasons are varied. Many respondents cited fear of government retribution; citizens didn’t give money to human rights groups because these would-be donors feared that the government would seek revenge. Other respondents said that human rights organizations themselves are unwilling to raise money locally because they don’t want to fall prey to local political pressures. Political parties, wealthy individuals, and local corporations may be willing to contribute money, but they’d demand too much in return. More often than not, respondents said, distant international donors exert less political control than potential local benefactors.

One of the most common explanations cited by our respondents was local philanthropic preferences. Although most every country has a charitable sector, individual philanthropists as well as charities in the Global South often prefer to channel their funds to concrete projects such as building schools or hospitals, or tangible services such as food, shelter and clothing. The work of human rights groups, by contrast, seems intangible and alien. Here it isn’t the human rights principles themselves that are the problem, but rather the human rights style, based as it is on research, public advocacy, policy analysis, and lobbying.

In international donor circles, human rights are a recognized theme, with routine application procedures and earmarked budgets. Local donors are likely to be skeptical and idiosyncratic, but international donors need little convincing; they already support that type of work. Although human rights advocacy work may be an accepted “thing” internationally, it has yet to become broadly popular in many Southern countries.

Finally, human rights workers must grapple with the unpleasant possibility that the work they do is simply not sufficiently useful. Development critic William Easterly writes eloquently that much international aid is wasted on projects for which there is little popular demand. When real demand exists, he argues, development entrepreneurs will figure out a way to supply that need. If contemporary human rights work isn’t attracting many local “buyers,” perhaps it hasn’t yet figured out how to offer something that sufficient numbers of people want, need, and are willing to support financially?

To raise more local money, human rights groups will have to hire new kinds of people, develop new social ties, and build new fund-raising capacities. They may also have to figure out a better “market niche,” in which they offer something so valuable that local donors, big and small, will want to pitch in.

Across the developing world, domestic rights groups have convinced international donors that their work is valuable, meaningful, and worth supporting. Now, the real task lies in convincing their publics, rich and poor, of the same thing.