United Nations COVID-19 Response/Unsplash

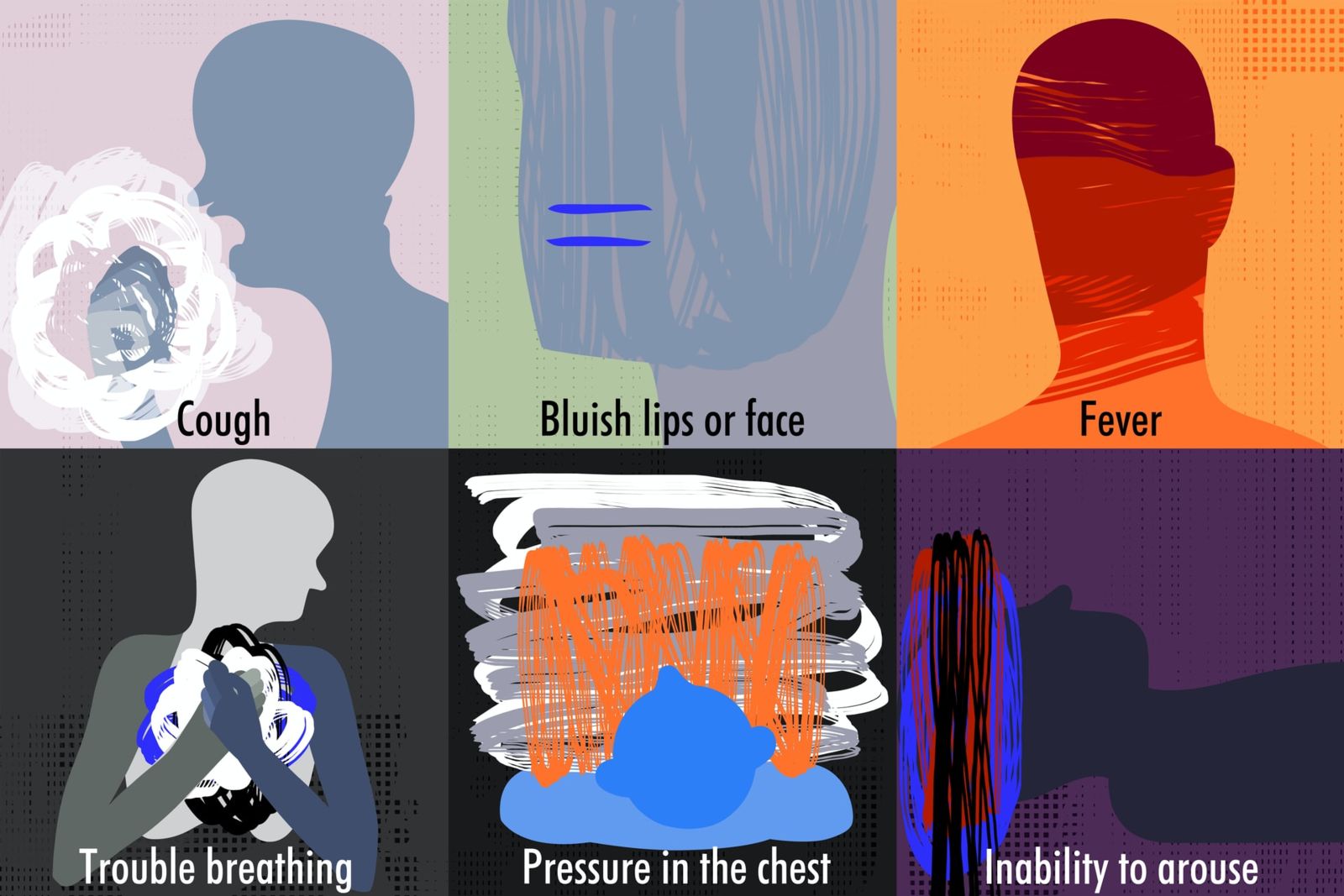

While Norway with its strict policy measures appears to have been broadly successful in suppressing Covid-19 and providing effective care, reports coming in during the first weeks of the outbreak showed a disproportionate rate of urban patients with immigrant backgrounds. While all population groups on paper have a right to health without discrimination, despite early translation of information material, the ineffectiveness in reaching people in immigrant communities with relevant information about the spread of the Coronavirus, sparked substantial criticism from civil society actors and activists. In response the government allocated funding to strengthen the information capacity of six NGOs—none of them community-based immigrant organizations—leading to further complaints about disempowerment, exclusion, and discrimination. Examples from Sweden, Germany, and the UK (as well as Canada) show similar challenges related to the provision of inclusive and non-discriminatory health information. We believe this issue to be one of the most important human rights dimensions of the Covid-19 response.

The UN Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) Article 12 and the CESCR Committee’s General Comment No. 14 on the Right to Health (GC14) require the state to ensure all residents access to institutions that can provide healing, care, and relief. This, according to GC 14 entails a duty to: “Provide education and access to information concerning the main health problems in the community, including methods of preventing and controlling them.” To be available, accessible, adequate, and understandable, health information must consider the interplay between factors like age, gender, language, social situation, level of education, cultural beliefs, and possible disabilities of individuals within different groups. This in turn, requires a participatory approach to the design of health and information measures.

Empirical evidence shows that information programs that, on paper, appear as the same for all may have different effects and outcomes for different population groups.

While formal equality is based on the principle that like cases are treated alike, substantive equality demand that different cases are treated differently. Empirical evidence shows that information programs that, on paper, appear as the same for all may have different effects and outcomes for different population groups and as such result in indirect or systemic discrimination.

National authorities have a wide scope of discretion to decide what information measures that under the circumstances are best suited to combat the spread of Covid-19. In the following, using Norway as a case example, we highlight seven elements that are key for a grounded and inclusive social and economic rights approach to health information:

- Plans for national health preparedness must integrate and mainstream a socio-cultural diversity perspective ahead of a crisis. The Norwegian national preparedness plans for infectious diseases has for many years been criticized by civil society for the lack of a social diversity perspective. Furthermore the CESCR Committee and the Race Committee has called for Norway to give better information about health rights to minorities.

- National information strategies must consider what information channels are suitable for reaching different population groups. While social media have made information more accessible, digital literacy and ability to access online information vary. When considering relevant information channels, sectors with high exposure jobs occupied by immigrants, such as taxi drivers, bus drivers, health workers, shop workers, or cleaners must be targeted.

- Information must be translated into the languages spoken by different population groups and disseminated via adequate digital and analog channels. This involves ensuring that posters carrying important information in the public realm (on buses, in public places, and in shops,) are made available in a range of languages in areas where immigrants live. Such information must be timely. While the Norwegian Institute of Public Health’s website provided information translated into various languages shortly a after the national measures were announced, efforts to reach immigrant communities were not sufficiently systematic and targeted.

- To be relevant, the information provided must be designed in a way that considers the living conditions among and within various population groups. One important factor is home size, given, for example, that 38% of Norwegian-Somalis live in overcrowded accommodation. In such circumstances, standard information about social distancing is not adequate. Instead concrete information about what measures people who live in crowded areas may resort to is needed. We know that gender dynamics within the family, for example, have implications for who is likely to bring the virus in and who oversees sanitation, cleaning, and caring.

- Information on how to protect oneself against infection should be communicated in a respectful and understandable manner. If a translation of public health documents lists health institutions unfamiliar to the community and uses technical and bureaucratic language, the message might get lost—and misunderstandings might arise. There may also be a need for a "cultural" translation of measures to prevent the spread of infection, with concrete examples that are likely to be understood. A related challenge is that some people view sickness and death as events that are determined by fate, or as punishment for breaches of social, religious or cultural norms. In such situations, working with experts on different religious, social and cultural beliefs and world views can help improve communication.

- Misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID-19 spread through social media present challenges for minority and majority communities alike. But this issue may require different public health approaches to dispel and correct falsities about health risks, mitigation strategies, and treatment.

- Lastly, information campaigns based on one-way communication are rarely effective. The content and structure of the information should be developed in collaboration with the affected communities and with organizations with linguistic and cultural competence, and knowledge about and trust from immigrant communities.

The Norwegian case is not unique. It epitomizes the weaknesses of “one size-fit-all” public health information campaigns. It also indicates that formal legislation is just the starting point: to promote universal access to health information, national preparedness plans must integrate an intersectional socio-cultural diversity perspective ahead of a crisis.