In March 2021, the Scottish Government released its National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report. The report calls and sets parameters for a human rights-based approach to national law- and policy-making.

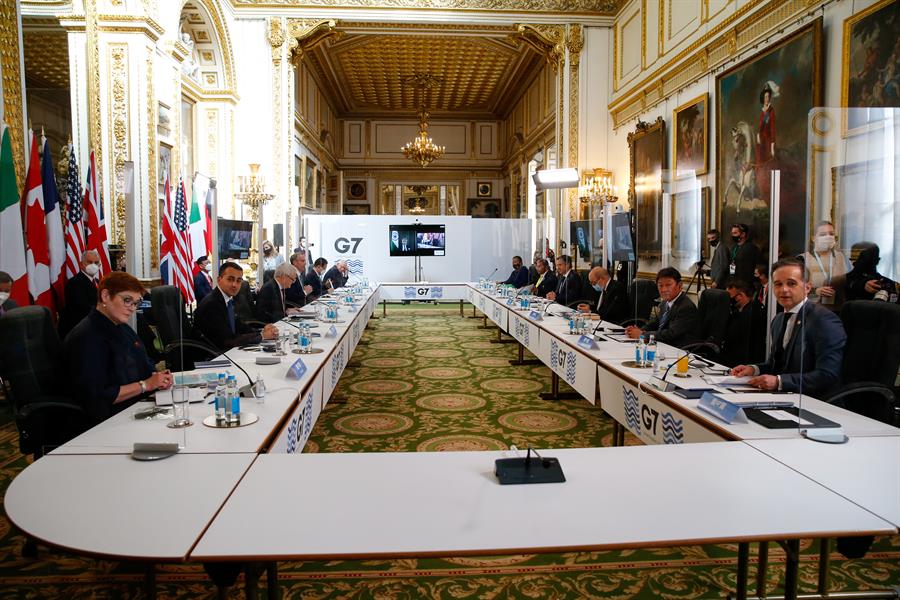

“Human rights-based approach” (HRBA) is a promising way to reframe and resolve many pressing contemporary issues such as persistent inequality gaps, relations with diverse minorities, Indigenous peoples, migrants and refugees, various social policies, public health measures and post-COVID rebuilding. As the G7 recently committed to a new “Build Back Better World” (B3W), forward-looking countries should take a close look at HRBA and embrace it fully for better governance, law- and policy-making in all fields and at all levels.

HRBA is a conceptual framework for the process of human development that is normatively rooted in international human rights standards and operationally directed to promoting and protecting human rights. It seeks to analyze inequalities which are at the heart of development and to redress discriminatory practices and unjust distributions of power that impede development and often result in groups of people being left behind.

The approach emerged some twenty years ago mostly within the United Nations system and has gradually gained ground across international development organizations and, to some extent, in municipal development. Despite being long-known at the international level, HRBA can still be viewed as “new” and “innovative” for national-level policy- and law-making.

The most recent example of embracing HRBA at the national level is Scotland, which has released a full report paving the way for institutionalization of HRBA. The Scottish National Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership Report is the result of a complex two-year endeavour involving high-level governmental officials, leading human rights scholars and a cross-section of civil society.

First, the Report calls for the full incorporation into Scotland’s law of all internationally recognized human rights, explicitly including economic, social and cultural rights as per the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as provisions of other core international human rights conventions, notably regarding elimination of discrimination against women, racial discrimination and the rights of disabled persons. This basic requirement sets the initial stage for HRBA—recognizing that areas such as education, healthcare, social security, cultural life, housing, food and clothing, water and sanitation are not matters of political choice or charity, but are the subjects of fundamental and imperative human rights.

Second, the Report calls explicitly to legislate the duty of progressive realization of human rights, and to establish a pre-legislative assessment process “to certify that any proposed [legislative] Bill complies with the rights contained within the framework and demonstrates where the proposed Bill contributes to the advancement of such rights”. In other words, not only is the Scottish legislative framework called upon not to violate human rights, but it is called upon to seek actively to improve and fulfill human rights. This provision is a huge leap towards the next key HRBA principle: all policy and law should directly aim at the full and effective realization of human rights.

The Report demands that the work towards realization of human rights be made part of the mandate of all public authorities through introduction of specific duties in respect of complaints mechanisms and oversight bodies to ensure human rights obligations are given full effect by all public authorities.

Not only is the Scottish legislative framework called upon not to violate human rights, but it is called upon to seek actively to improve and fulfill human rights.

Finally, the Report calls for establishment of participatory and accountable legislative, executive and justice-making processes, including through additional and improved human rights complaints and remedy mechanisms, introduction of the explicit right to effective participation, and so forth.

As welcome and hopeful as this appears, there are certain aspects on which the new Scottish approach could still be improved in terms of a strong and comprehensive HRBA. For example, there should be specific focus on pro-actively closing gaps between the most vulnerable and the rest of society and elevating “consultation” of rights-holders to their fully engaged participation.

For human rights advocates around the world, the Scottish report stands out for its forward-looking character—distinguishing it from the typical piecemeal and reactive approach found elsewhere even amongst so-called “advanced” democracies and countries concerned with social justice. For example, instead of continuing to treat human rights as just “an area of law”, the Scottish report calls for a comprehensive mainstreaming of human rights across the board.

HRBA is explicitly referenced as the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda’s foundational principle, and HRBA is argued to be key for figuring out the COVID-19 crisis and for post-COVID rebuilding. Globally some governments and organizations put HRBA at the basis of policy-making and programming in such areas as international development, housing, health, social protection and care policies. Among those taking some steps in this direction are New Zealand and Canada.

Canada appears especially well-placed to follow and could enhance the demonstration effect of interest for others. In the first place, Canada presents itself as a global leader in advancing gender equality and human rights and some explicit references to HRBA can be found in Canadian international assistance documents and around the new Canadian National Housing Strategy. A number of Canadian organizations have called for a human rights-based approach for policies in respect also of national security, drugs, migration, development services, and city zoning, while in Canada’s largest province (about 3 times the population of Scotland) the Ontario Human Rights Commission has issued a Policy statement on a human rights-based approach to managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the same time, Canada does not engage with HRBA systemically—despite the common public belief that Canada is already a “rights-based” country. HRBA is not a topic of discussion in major for a such as law-making, policy-making, academia or research funding institutions in Canada, although there is increasing public interest in substantial and systemic issues like racism, inequities, the need for reconciliation and equal opportunities. Some relevant initiatives are advanced by certain NGOs (as mentioned above), arise within a few university courses and are occasionally mentioned during scholarly conferences, but these have not resulted in a comprehensive or system-wide effort like the one tabled now in Scotland. Yet, as a G7 member State and as a loose federation, the application of HRBA in Canada—in all fields and at all levels—would provide important references, if not a model, for others to follow. Indeed, HRBA carries huge potential for Canada and other States to reframe and resolve many pressing issues, including relations with diverse minorities, Indigenous peoples, permanent and temporary migrants, and various social policies, as well as COVID measures and post-COVID rebuilding.

Whether Canada or another forward-looking country, it is past time to take a close look at HRBA and embrace it for law- and policy-making in all fields and at all levels. The pioneering example of Scotland offers good guidance in this regard. Establishing a National Task Force for HRBA, similar to Scotland’s Taskforce for Human Rights Leadership, would be a good starting point. Several research and educational institutions, as well as some United Nations bodies, can provide sound methodological and advisory support. If the world really will “build back better” after COVID-19 as the G7 intends, Scotland has shown an important way of doing so. Now the world should follow.