Tracing the path of the virus has been a particular challenge this pandemic year, but so has been following the flow of money. Which companies have governments allowed to continue operations, while certain groups are left strapped for cash? There have been clear winners and losers when it comes to managing finances through this pandemic and calculating the bottom line, but there also have been blatant cheaters, including those who have readily bypassed their human rights obligations in order to squeeze profits out of what continue to be trying financial times. While some corporations are trudging forward, many human rights defenders (HRDs) feel threatened by big-business, drained by fluctuating market prices, and neglected by their governments’ stimulus packages.

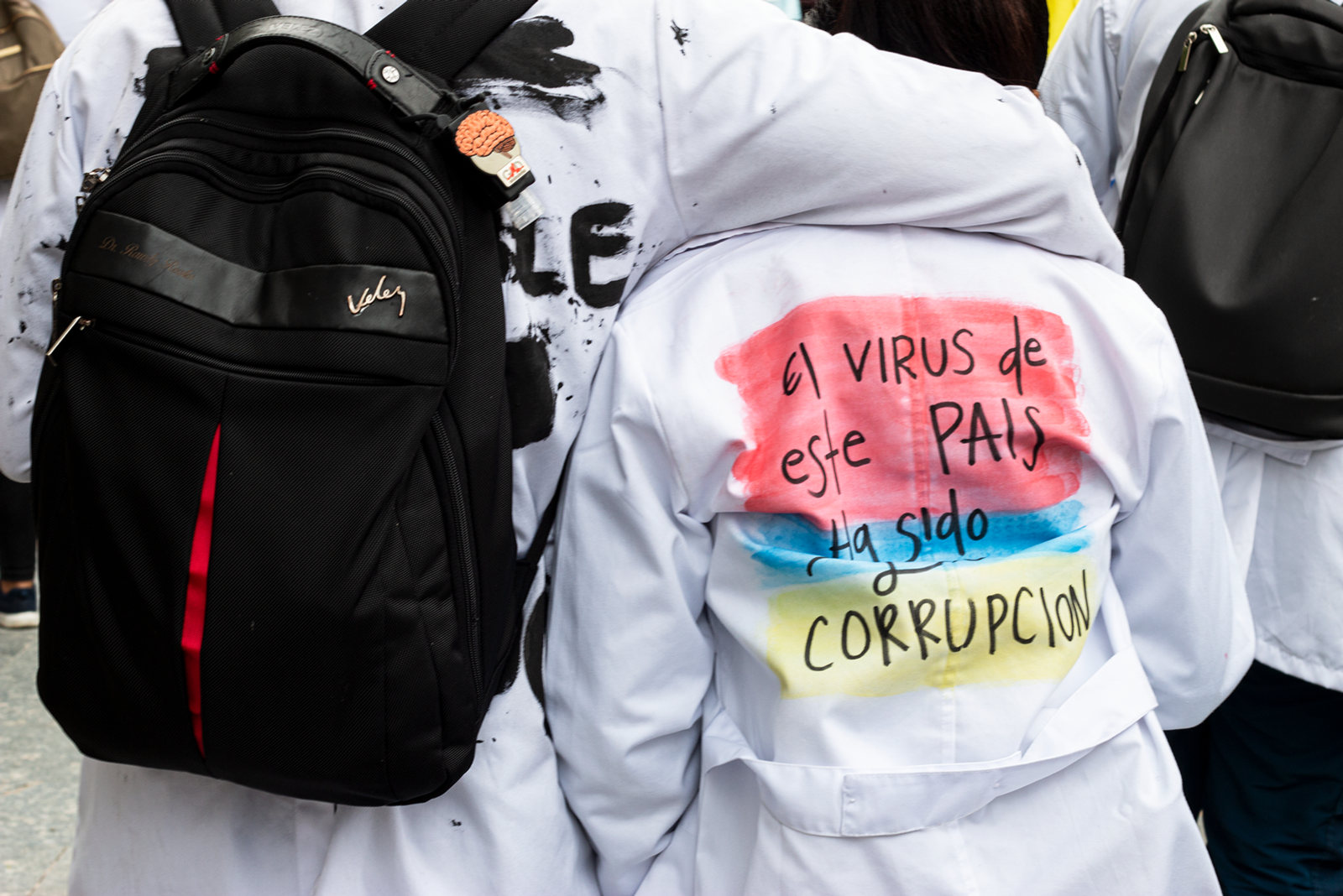

Description: Protesters take to the streets in Colombia calling for equality (May 2021). Source: Nathalia Sie

Businesses determined to turn a profit, at any cost

Opportunistic states and armed actors are not the only ones using the pandemic to their advantage; some private corporations have seized 2020 as a chance to move forward with their business plans without due consultation or fear of community backlash. According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, there were 286 business-related attacks against HRDs between March and October 2020, which represents a 7.5% increase compared to the previous year.

On a variety of occasions, governments around the world have prioritized profits over fundamental rights and freedoms during a crisis. This is most clearly exemplified by the continuing attacks against the Southern Peasants Federation of Thailand (SPFT). Disputes over the SPFT’s right to their territory have existed for years, but tensions escalated last October after the attempted murder of Dam Onmuang, a member and leader of the Santi Pattana Community. Protection International continues to call for a thorough examination of all evidence related to the land dispute between the palm oil company in the area and the SPFT, as well as an impartial investigation into the attempted assassination of Mr Onmuang. The perpetrator was recently indicted and is awaiting a final decision on the prison sentence, but the intellectual authors of the crime have yet to be held accountable.

According to Sulakshana Lamubol from Protection International Thailand, “Due to the fear of what has happened to Mr Onmuang, he isn’t able to leave home to work and therefore had to hire workers to do agriculture work on the land for him. Since the incident, he has lost approximately $300 -$500 per month, which was his average income before the incident.”

In Mesoamerica, extractive companies and mega-projects have continued throughout the pandemic—either operating illegally or with special permissions from the government. During his election campaign in 2019, President Giammattei promised to restore confidence in Guatemala’s investment environment—particularly for transnational mining companies—and it appears he continues to operate in this way, regardless of the unforeseen pandemic. The Fenix nickel mine in Guatemala, which is operated by the Switzerland-based Solway Investment Group, continued operations despite the fact that unnecessary businesses were ordered to shut down in March 2020. These types of companies create water contamination that has driven away the fish and air pollution that cause respiratory problems—which is particularly concerning during a pandemic in which the virus attacks the lungs.

In effect, some companies have used COVID-19 as a global distraction from the harms they are imposing on local communities and the planet.

In January of this year, Protection International joined 194 other international organizations in denouncing the attempted assassination of Julio David González Arango—a HRD and member of the peaceful resistance movement against Pan American Silver’s Escobal mine in Guatemala—and two other members of the resistant movement who received death threats. Meanwhile, the mining company continues to carry out community projects that “foment tension and social division given that all operations should be suspended.” According to the statement sent to the company [by a nearby, Indigenous community], “The [Xinka] Parliament has also denounced the company’s community outreach programs as coercion and in violation of the ‘free’ nature of the consultation.”

There are numerous reports of partially or fully State-owned enterprises completely evading their responsibilities of due-consultation with communities, under the false pretense of impossibility. Short-sighted governments have used economic hardship as an excuse for endorsing destructive operations, and as Mauricio Angel from Protection International explains, “In effect, some companies have used COVID-19 as a global distraction from the harms they are imposing on local communities and the planet.”

Financial instability impedes the right to defend human rights

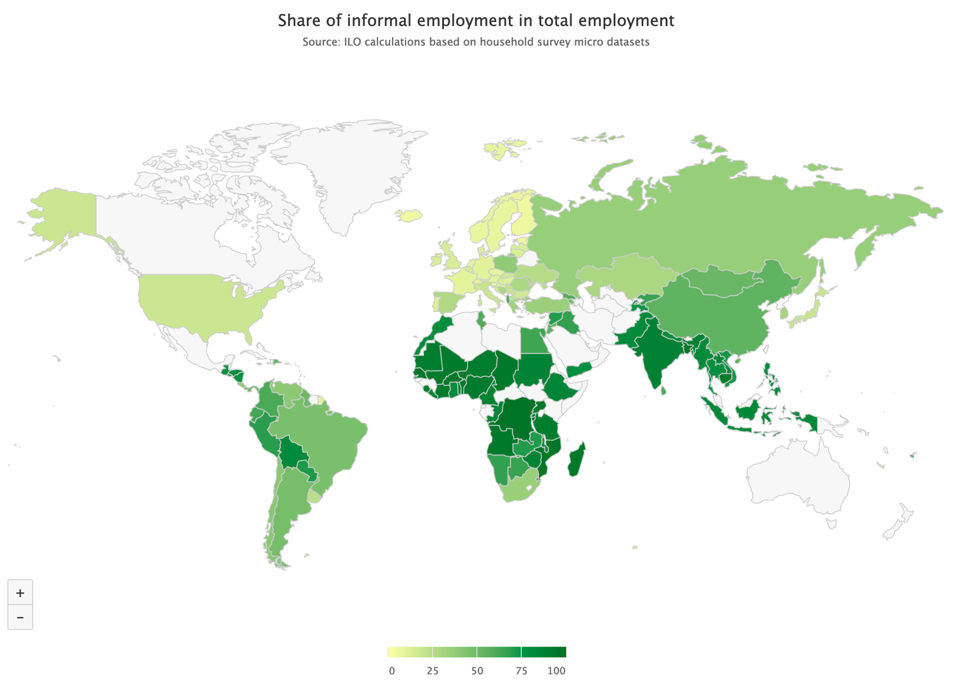

One of the most pervasive and importunate issues facing many HRDs today is the reality that money is tight. Food is more expensive, the global unemployment rate has hit its highest percentage in decades, and costs for COVID-19 related healthcare leave many with narrowing margins of disposable income. Confinement measures disproportionately affect those who are dependent on the informal work economy, which according to the International Labour Organization (ILO), is roughly six out of every 10 workers worldwide. The share of informal employment in total employment is particularly high in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia, with countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo reaching as high as 97%. And as Liliana De Marco Coenen, the executive director of Protection International, put it: “It is important to remember that defending human rights is rarely a paid job, especially for those that act out of urgent necessity.”

Our colleagues from the Democratic Republic of the Congo rated “food insecurity” as the most pressing issue for HRDs in the country. The Food and Agriculture Organization’s most recent Food Price Index indicates that the average price for food commodities rose yet again in January 2021 after a steady nine-month increase. In April and May 2020, Action pour la Lutte Contre l'Injustice Sociale and Rainbow Sunrise Mapambazuko showed that an increasing number of LGBTI HRDs in the country have become homeless, which has contributed to their social instability, food insecurity, and poor health.

And the cost of contracting COVID-19 is, of course, too high in every sense. This is especially true for those HRDs working within the UN’s categorically Least Developed Countries (LCDs), where one in two health care facilities does not have potable drinking water, further putting healthcare workers and patients at risk. Addressing the basic needs of HRDs is a critical first step towards enabling their right to defend human rights, which is a right that should not and cannot be quarantined.

There is still a great deal of work to be done while we are waiting for the world to financially restabilize and safely re-open. We can start by reflecting on the lessons learned related to business and human rights and calculate the importance of monitoring and oversight. Civil society organisations can continue to work on improving coordination amongst themselves to respond more quickly to present and future borderless crises. We could also work better together to counter feverishly damaging narratives about human rights defenders even before they’ve gone viral. But mostly, we would like to echo the IACHR and the Zero Tolerance Initiative’s statements urging that states must do more to protect and preserve the work of human rights defenders for the remainder of the pandemic and beyond, with a particular emphasis on the needs of women, rural, Indigenous, and other minority HRDs who are disproportionately at risk. States need to decrease the cost of defending human rights by lowering the risks associated with doing the work. While vaccines do provide a light at the end of the tunnel for fighting COVID-19, it is critical that HRDs are not left in the dark.

This article is part III of a three-part series on COVID-19 and human rights defenders. Here you can read part I and part II.